MirrorMirror: Illuminating the black box for the everyday internet user

MirrorMirror is a web extension that tracks a user’s search engine queries ultimately compiling a digital profile that characterizes the user. The goal of the non-profit tool is to encourage awareness and potentially behavioural change surrounding user’s interaction with corporate algorithms. This blogpost will consider the tool from an academic and contextual framework, as well as providing a thorough methodology depicting our processes, concluding with an analysis of the products limitations.

MirrorMirror

The MirrorMirror logo

The project objective is to start an internet “awareness” charity. One of our “awareness” tactics is to create a web extension, MirrorMirror, that extracts a user’s search queries from search engines, and analyzes and categorizes the data into a user-friendly visualization. The goal is to create digital profiles of internet users, ultimately raising awareness of the internet behavior that defines our digital footprints.

While extensions such as Mozilla Lightbeam and Ghostery are concerned with mapping trackers and visualising a pathway of your digital footprint, MirrorMirror is different. We are not concerned about exposing the cartography of the internet but rather visualising how we appear along that pathway. Exposing who is tracking us is commendable but we want to reveal how we are being characterised ultimately revealing the digital doppelganger hiding within the browser of every internet user.

The homepage of MirrorMirror

The Larger Picture

We are divided. Not as a people or a nation – not on such a socio-political level – but as individuals. The endless amounts of personal data that we have dispersed over the web in fact represent tiny fractions of ourselves: the accounts that we’ve created on various websites, our social media profiles, search queries, financial transactions, and so on. In this sense, as Deleuze would put it, we have become dividuals – or, put simply: individuals that are divisible (1990).

Elaborating on Deleuze’s notion of dividuals, Cheney-Lippold introduces the concept of a ‘new algorithmic identity’. This identity, he argues, is the product of web analytics firms that track, analyze, and categorize our online behavior at the hand of mathematical algorithms. These algorithms determine one’s identity traits, while at the same time defining the actual meaning of those traits (2011).

Our identity formation has thus entered the realm of the algorithm. A realm that is described extensively in the work of Gillespie (2014), from which this article will also draw. Behind algorithms stand the corporations that built them, which ultimately thrive on profit maximization. It is therefore also important to take into account the broader context that describes how the corporation plays a central role in a society that consists of dividuals: a ‘society of control’ (Deleuze 1990).

We have become dividuals, individuals that are divisble and easily controlled by corporations.

Relevance

MirrorMirror highlights a necessary intervention where internet identity is concerned. “The more consumed we are with our use of the internet the more we are losing control in defining who we are online” (Cheney-Lippold, 16). MirrorMirror acts as a transparency tool that highlights this definition for any internet user by portraying their digital doppelganger as seen through the eyes of a search engine.

A visualization of an individual’s e-mail inbox. Each circle represents a company or institution that interacts with the individual over mail. The larger the circle, the more interaction.

In visualising part of our digital footprint we are exposing the abilities of corporate algorithms and in turn somewhat illuminating the black-boxes that track our every click. By seeing their digital profile an internet user can then consider how they interact with certain sites, but ultimately question their actions online.

This is a popular arena of discourse especially where self-tracking is concerned. Deborah Lupton hails the notion of self-tracking as “unavoidable” regardless of it being imposed or voluntary (2014:15). Considering this notion of inevitability, through MirrorMirror we offer self-tracking from the neutral “voluntary” angle in order to expose the characterisation incurred by the “imposed”. New social networking sites based entirely around these notions of privacy retention such as Ourbook or Masques embody the belief that users can have the benefits of a normal social network “while enjoying control over their privacy and intellectual property” (Buchegger & Datta: 8). These examples employ the method of P2P networking to enable a decentralised network to manage the flow of user data.

In terms of a critical intervention our project channels the work of Mattern who is keen to expose the (physical) infrastructure of the internet. In much the same way we are “constituting…a new human experience” (Mattern: 2) by revealing a hidden depth of the internet (albeit digital), but a phenomena so relevant as it concerns us as the “dividual”.

The extension also speaks to a critical art framework as an increasing number of artists are harnessing self-tracking in their work (see Urist). Whilst we are highlighting our “dividualisation” the wider artistic context for Urist and indeed MirrorMirror is to achieve “greater awareness of complex matters in a modern world”.

Large corporations are shaping our internet experience with use of our self-sacrificed data and in turn are defining us as dividuals (Deleuze 1990, p.5). MirrorMirror will encourage the average internet user to contemplate who is in charge of this data collection, how it is obtained and indeed how else it could be used. It will allow a user to consider Hallinan & Striphas’ notion of our current climate where engineers—or their algorithms— are becoming important arbiters of our culture (p.131).

Methodology

As the Cambridge Analytica 2016 US electoral project (building forth on research by data scientist Michal Kosinski) was deemed successful in gathering and categorizing extensive amounts of personal information alongside users’ Facebook interactions, we felt inspired to emulate some of their strengths for our product. Thus, central to MirrorMirror will be a machine-learning algorithm that processes information of its own accord, undertaking a process of collaborative filtering to reach its conclusion of the user.

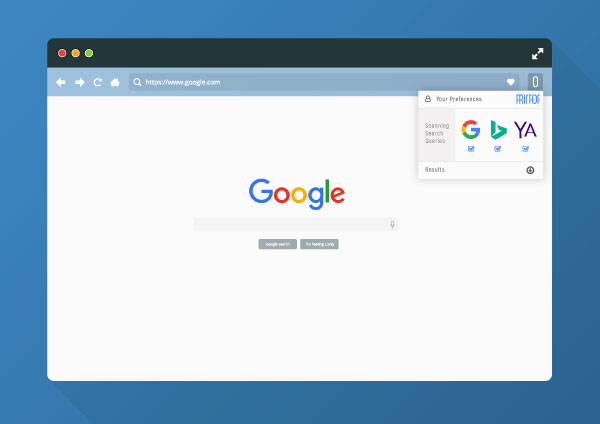

The MirrorMirror-extension after installation

MirrorMirror is a browser extension, easily installed and activated by any average internet user. It works with Chrome, Firefox, Safari, and Edge. Upon installation the user will agree to be tracked on all major search engines (Google/Bing/Yahoo). Users’ search queries will relay back to the extension and within a one-week window, they will be provided with a visual representation of their digital self. The user will be prompted to save this visualization in the form of an interactive PDF-document on their local hard drive. Updated versions can be downloaded anytime and the user will be prompted to do so on a monthly basis.

By acquiring search engine queries and its subsequent results MirrorMirror sorts data into specific categories, ranging from hobbies to career, from interests to fears, and so on. The sorting and categorizing is made possible by a machine learning algorithm, that amasses user data from all users. The more interaction, the more accurate the processes of categorization will become.

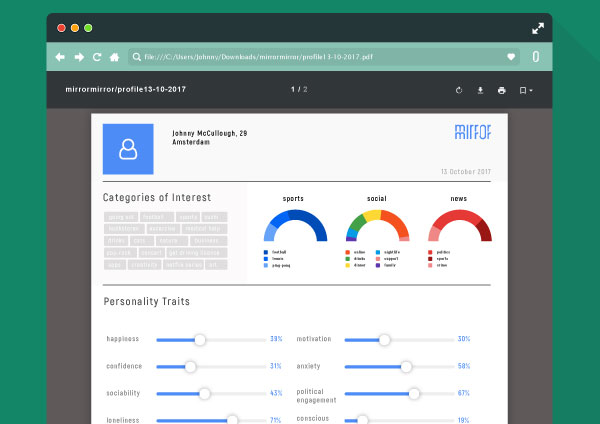

The visualisation will present a series of interactive infographics that clearly display your interests and dislikes, political and sexual preferences and so on. Another section which forms through our collaborative filtering algorithm would be a personality overview. Based on other user searches the algorithm will make suggestions of a user’s implied traits such as mood, social skills, and characteristics.

An example of an interactive PDF-file that displays user preferences and characteristics

MirrorMirror is not a commercial party and as such it is not in our interest to exploit the data of our users. Hence the reason that security is paramount in our processes. User data is never stored as one data-set on a server, nor is it ever shared with third parties. Rather, the data is fragmented and spread across many of our different encrypted servers. Much like cryptocurrency (and the previous social media examples) our extension will lend from methods of “peer-to-peer networking and public key cryptography” similar to the systems of the “blockchain” (Swan: vii). However as we are not interested in the inclusion of third parties, our P2P network will only consist of our servers each housing only some user data. In a sense we are combining the P2P with the client server model. By using a three-step verification (password, identifying question, and SMS-code) a user can request their “profile” which will then be validated by a network of nodes to determine the authenticity of request. Once determined the data will be merged, encrypted and sent to the users local drive.

Analysis

MirrorMirror aims to shed light on the black box that is a search engine

MirrorMirror gives users the opportunity to develop an understanding of how algorithms can create a personal identity of their activity online. Our work acknowledges Mattern’s notion that citizens have “a right to know what is going on inside those black-boxes” (50) and indeed our project will provide users with insight into an issue that they are normally kept in the dark about (Gradwell 249). Through MirrorMirror we are highlighting a data infrastructure that is normally inaccessible to the user. Furthermore in doing this we are demonstrating how a user’s online behaviour can be characterized.

Technology can provide benefits to one set of people yet adversely affect another.

MirrorMirror provides a divergent approach to help users become more aware of algorithms. By visualising a user’s web traffic into a digital profile, MirrorMirror can show the user how algorithms analyse their behaviour and use it to target their advertising, for example. This could help users to think more critically about their actions as well as the information they divulge online.

We understand that a user’s interest may wane month after month however the monthly prompt function will remind users their digital profile will only become more detailed (and more accurate) the longer the user has it installed. Also it is unlikely for a user to be too deterred as the extension is very low maintenance; users would continue with their searching-life unconsciously contributing to the input of data. After continued use we would hope its poignancy would become accurate enough to illuminate to a user how much information we part with digitally.

We understand that users may have issues surrounding privacy. We would firstly hope that MirrorMirror’s position as an internet “awareness” charity over that of a profit-driven corporation would instill a sense of trust between us and the user. Secondly our blatant transparency in regards to security and data storage can quash any further anxieties of users.

A limitation in our concept is that MirrorMirror only analyses data taken from search queries and their results, which means that internal actions on platforms such as Facebook and Twitter would not be included. To include the tracking on other such platforms would be a logical addition to our a extension however unfortunately it would be quite an impossible task to include such capabilities. We acknowledge that this could lead to the data profiles not being as accurate as ones created by GAFA for example however it is designed to be a snapshot. We still feel that users would gain a knowledgeable insight into their digital self.

As well as encouraging awareness we also envisage users potentially altering their behaviour both online and offline in reaction to their profiles. MirrorMirror can not only highlight a user’s online persona but also emphasize the differences with their offline personality too. If there is a considerable difference they might wonder if their personalised online experience is addressing and therefore only stimulating a certain part of themselves. While this could be a positive consequence of our extension it could be a cause for concern as the user might not be pleased with their results. It would therefore be paramount in our infographics to highlight that MirrorMirror is merely a speculative tool and the characteristics portrayed are not necessarily accurate or indeed that of companies such as GAFA.

Role of new media

By creating a web extension thats turns data into a visualized ‘digital profile’ mirroring the user, we are making use of new media elements to create an intervention into how people think about using the internet and new media all together. The way the extension operates is solely dependent on the use of new media and through creating this extension we are introducing a new critical discourse surrounding online behaviour.

References

Beer, Stafford. Platform for Change: A Message from Stafford Beer. J. Wiley, 1994.

Buchegger, Sonja, and Anwitaman Datta. ‘A Case for P2P Infrastructure for Social Networks-Opportunities & Challenges’. Wireless On-Demand Network Systems and Services, 2009. WONS 2009. Sixth International Conference On, IEEE, 2009, pp. 161–168.

Cheney-Lippold, John. ‘A New Algorithmic Identity: Soft Biopolitics and the Modulation of Control’. Theory, Culture & Society, vol. 28, no. 6, Nov. 2011, pp. 164–81. CrossRef, doi:10.1177/0263276411424420.

Crampton, Jeremy W., and Stuart Elden, editors. Space, Knowledge and Power: Foucault and Geography. Ashgate, 2007.

Deleuze, Gilles. ‘Postscript of the Societies of Control’. The MIT Press, vol. 59, 1992, pp. 3–7, www.jstor.org/stable/778828.

Gillespie, Tarleton. ‘The Politics of “Platforms”’. New Media & Society, vol. 12, no. 3, May 2010, pp. 347–64. CrossRef, doi:10.1177/1461444809342738.

Gradwell, John B. ‘The Immensity of Technology . . . and the Role of the Individual’. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, vol. 9, no. 3, Oct. 1999, pp. 241–67. CrossRef, doi:10.1023/A:1008977001294.

Haimson, Oliver L., et al. Digital Footprints and Changing Networks During Online Identity Transitions. ACM Press, 2016, pp. 2895–907. CrossRef, doi:10.1145/2858036.2858136.

Hallinan, Blake, and Ted Striphas. ‘Recommended for You: The Netflix Prize and the Production of Algorithmic Culture’. New Media & Society, vol. 18, no. 1, Jan. 2016, pp. 117–37. CrossRef, doi:10.1177/1461444814538646.

Hardey, Michael. ‘Life beyond the Screen: Embodiment and Identity through the Internet’. The Sociological Review, vol. 50, no. 4, Nov. 2002, pp. 570–85. CrossRef, doi:10.1111/1467-954X.00399.

Kosinski, M., et al. ‘Private Traits and Attributes Are Predictable from Digital Records of Human Behavior’. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 110, no. 15, Apr. 2013, pp. 5802–05. CrossRef, doi:10.1073/pnas.1218772110.

Lupton, Deborah. ‘Self-Tracking Cultures: Towards a Sociology of Personal Informatics’. Proceedings of the 26th Australian Computer-Human Interaction Conference on Designing Futures: The Future of Design, ACM, 2014, pp. 77–86.

—. Self-Tracking Modes: Reflexive Self-Monitoring and Data Practices. 2014.

Mattern, Shannon. Code and the City. Routledge, 2016. CrossRef, doi:10.4324/9781315685991.

—. ‘Infrastructural Tourism’. Places Journal, July 2013. placesjournal.org, doi:10.22269/130701.

Nakamura, Lisa. Cybertypes: Race, Ethnicity, and Identity on the Internet. Routledge, 2002.

Swan, Melanie. Blockchain: Blueprint for a New Economy. First edition, O’Reilly, 2015.

Yeung, Karen. ‘“Hypernudge”: Big Data as a Mode of Regulation by Design’. Information, Communication & Society, vol. 20, no. 1, Jan. 2017, pp. 118–36. CrossRef, doi:10.1080/1369118X.2016.1186713.