Stop trying to script my life

The colonization of the empty state and nudges as contested territory.

On another day at the office, something remarkable happens. I manage to clean up my entire email inbox. Not being the kind of person whose inbox is often empty something appears that I haven’t noticed before. The empty inbox displays an animation of a tiny hot air balloon. The colors bright and happy, the edges smooth and clean. In the background a pink, perfect circle and two little animated clouds. ‘All done for the day!’ I read. ‘Enjoy your empty inbox’.

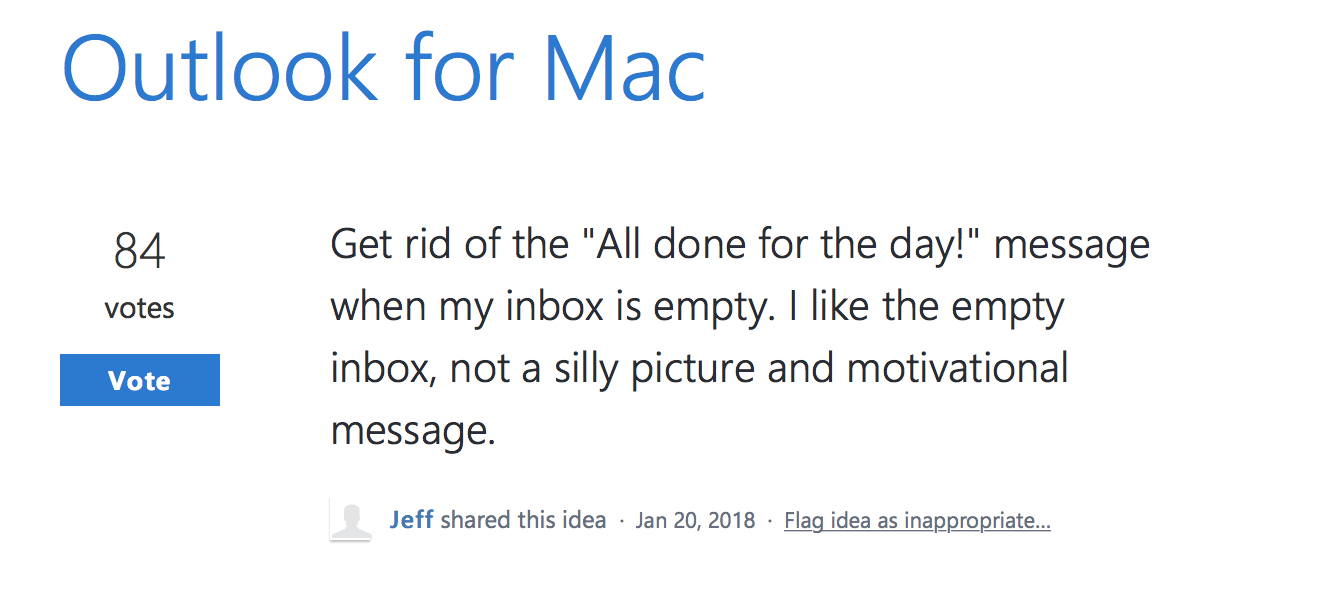

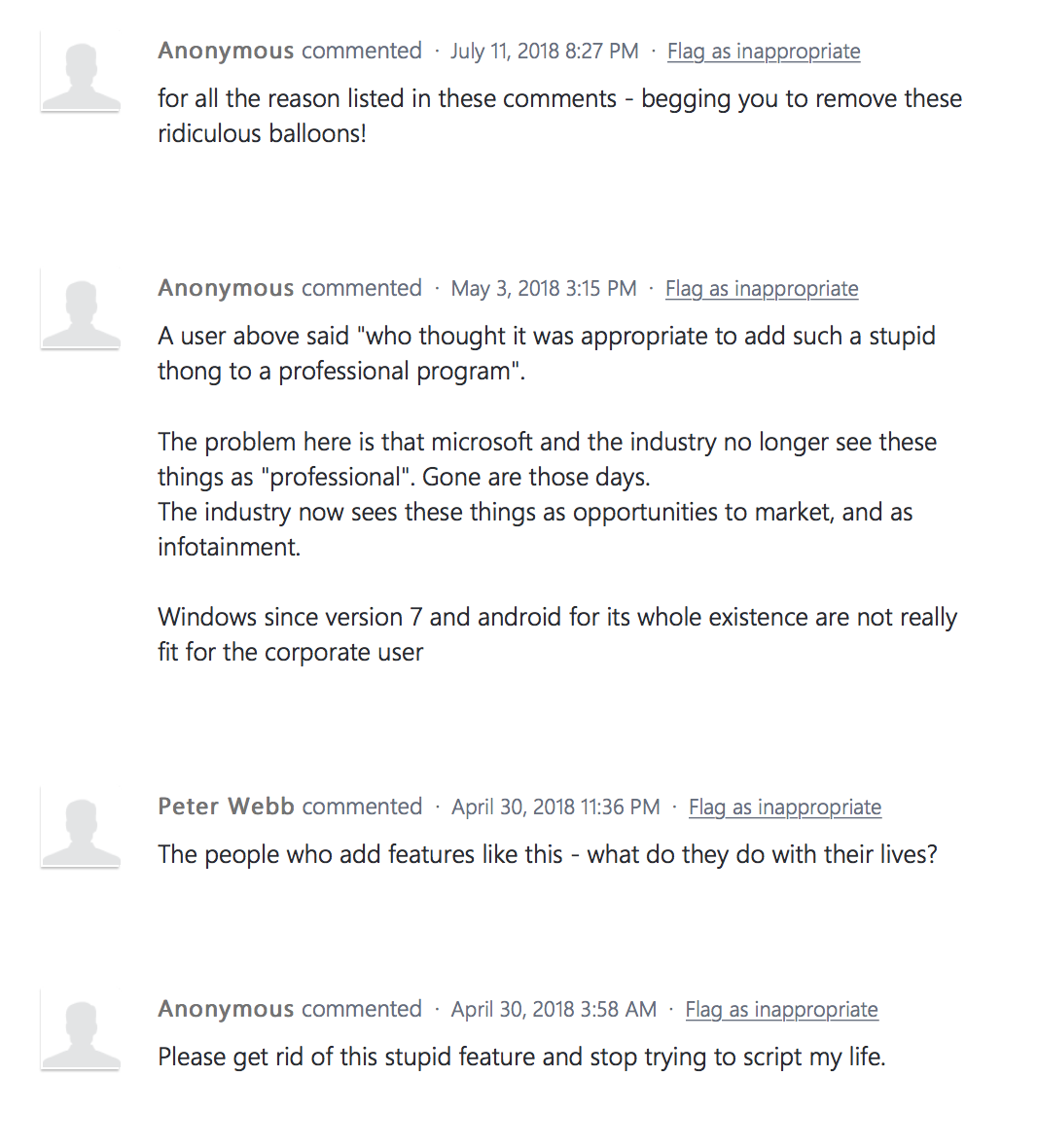

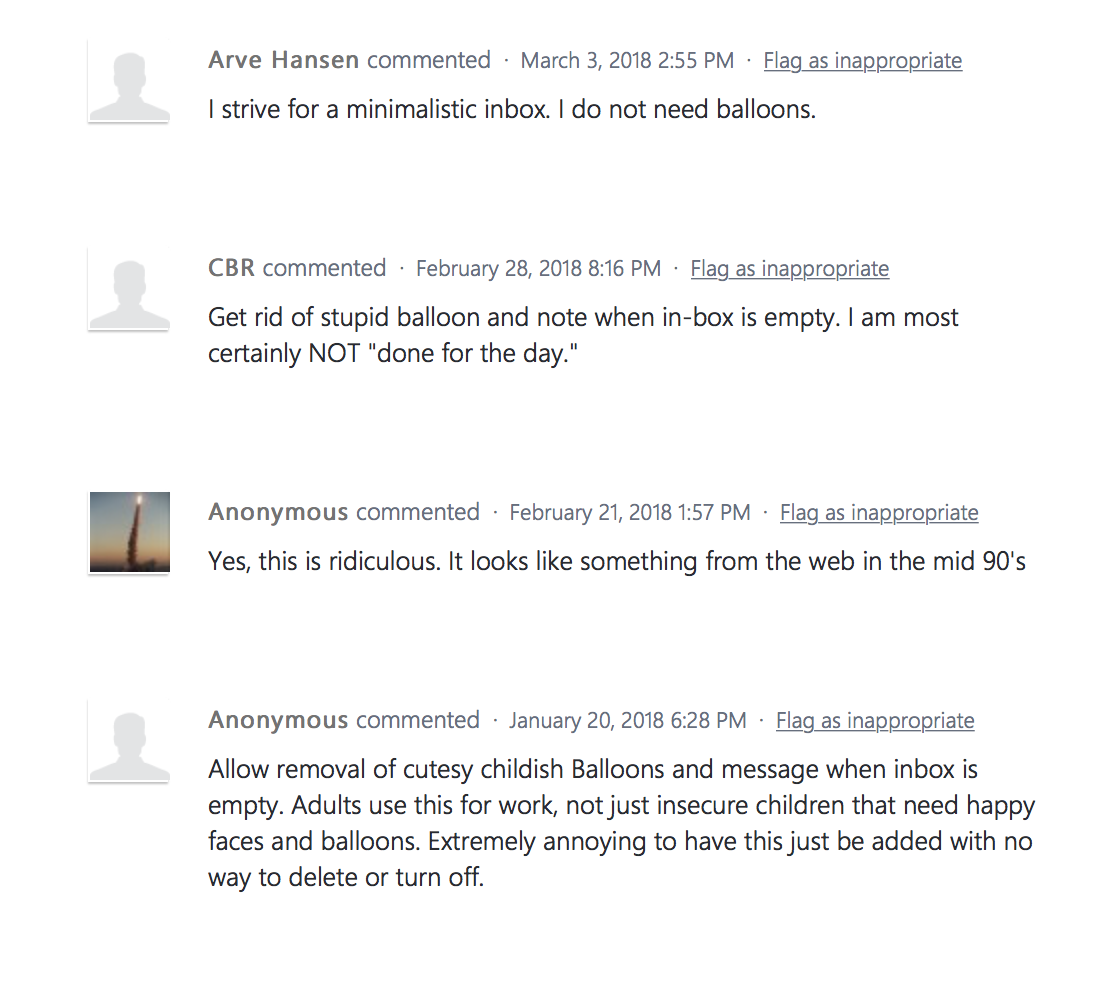

I am highly annoyed. And so are many Outlook-users with me, As I try to find out when this feature was included (beginning 2018). I find a forum full of frustrated requests to get rid of ‘the childish balloon’.

Empty states

This hot air balloon, I soon learn from a friend who is user interface (UI) designer, is an example of what is known in his field as ‘empty state design’. The ‘empty state’ referring to an empty inbox or a new account which has no posts or other data yet. As is pointed out on a UI design blog, it is an ‘opportunity to nudge users to start engaging’. Once the “godfathers” of the nudge theory Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein had to stress that ‘everything matters’ in design, for ‘small and apparently insignificant details can have major impacts on people’s behavior’ (Thaler and Sunstein, 2008, p.3) . It was taken to heart in the world of UI design. We find our interfaces crammed with nudges, trying to influence our behavior, and affordances, constantly guiding us, requesting, encouraging, discouraging. Triggering and engaging. All terrains, including the previously neglected empty states, are colonized by nudges. As the UI design blog explains:

‘As mentioned, an empty state is an excellent opportunity to encourage users to interact with the product. You don’t want to leave them in the wilderness of your UI.’

– Justinmind blog

In the overcultivated environment of the user-interface, we are clearly not meant to explore and wander around unattended.

Make it happen

But a nudge must be carefully crafted to do what it is supposed to do. In the blogpost the designer stresses how important the right level of playfulness, the right tone and copy is. In this case the balloon seems to have failed to ‘engage’ or ‘encourage’ the user. Unless the ‘all done for the day!’ shout-out is meant as an encouragement to consider work as done and go home to enjoy some free time, which is highly unlikely. And the tone of the message just seems too colorful and playful for a program that is mostly used in a professional setting. But according my friend the UI designer, informal and playful is the norm, leading to, in his words, ‘clownesque excesses’ and irritated users. As if to prove this point, that same afternoon I encounter another empty state design feature – including another balloon animation. A balloon with a smiling face drawn on it, in this case. And now I see ‘playful’ empty state design everywhere. The latest being an empty state message reading ‘Your Dropbox feels a bit lonely’.

All these nudges are, whether successful in their implementation or not, building blocks of carefully crafted and often extensively tested interfaces, with very specific aims, which in turn rests on sometimes explicit but often implicit assumptions. Mel Stanfill (2013) pointed out that interfaces can be read and analyzed as discourses, both reflecting and reinforcing social logics. Through discursive interface analysis, we can expose the underlying assumptions about the normative and ‘correct’, but also investigate their productive power. In this line, Evgeny Morozov (2015) points out that all this nudging rests on a particular assumption of how humans fundamentally work; as utility-maximizers, merely responding to direct incentives of rewards and short-term gratification. Morozov explains how this is not only a widely accepte social logic in technology design, but becomes productive, a self-fulfilling prophecy. Once people start getting rewards for tasks, their behavior changes. They become more focused on the rewards than the broader picture, more focused on their self-interest than the common goal.

Dreams of idealized futures

Morozov unravels the value system behind the nudges and rewards. Similarily, Christian Ulrik Andersen and Søren Pold are developing an interface critique, but with an emphasis on technology as a dreams, as a myth of idealized futures:

‘..to discuss how technologies perform as dreams of emancipatory or other post-semiotic idealized futures, and argue for the need for an interface mythology that critically addresses the technologies as myths; and unravels them as value systems and tools for writing – of both future functionalities and future cultures.’

– Ulrik and Pold, 2018, p. 14

This, they point out, is even more necessary as interfaces are becoming more diverse and ubiquitous. Ulrik and Pold coin the term ‘metainterface’: a multi-layered media interface, that includes voice-driven interfaces, the internet of things, smart cities, wearables and so on (Prior, 2018). This metainterface is omnipresent, and so accepted and integrated that it will become invisible. Ulrik and Pold see great potential in awareness-raising art and design, such as Benjamin Grossers ‘Demetricator’ projects, extensions that hide metrics on Facebook or Twitter. This way we become conscious of the workings metrics, a significant and effective category of nudges. José van Dijck has described in her critical theory of social media, how metrics produce a sociality based on neo-liberal principles of competition. The critique on the heavy emphasis on number of likes, friends, retweets, shares is not limited to the sphere of design-art and academia: Kayne West recently pleaded for the option of using social media without the numbers.

There are many more examples of the ‘inner workings’ of the interface being recognized and criticized. From regretful former Google-employees, to psychologists and media-platforms: if anything, the awareness of the manipulative aspects of nudges in technology design and its effects on our behavior, seem to grow. It seems that the interface, and its many nudges, are not yet fully accepted and invisible, but highly contested terrain.

Digital health

The technology companies and their UI designers are responding. Both Google and Apple now have their ‘digital health’ or ‘wellbeing’ products that mean to help us fight the addictive characteristic of their technologies. The irony is hard to overlook. Furthermore, if anything, a nudge-free safe space as an add-on and not the default, works as an exception that only solidifies the rule.

The silly hot-air balloon disappeared while new messages poured into my inbox. I am waiting for an artist building a ‘reclaim the empty spaces’ app. To offer at least some escape from the pestering sales-talk that haunts the cultivated landscape of the metainterface.

Literature

Andersen, Christian Ulrik and Pold, Søren (2018). “Interface Mythologies – Xanadu Unraveled.” In Interface Critique Journal Vol.1. Eds. Florian Hadler, Alice Soiné, Daniel Irrgang DOI: 10.11588/ic.2018.0.44738

Grosser, Benjamin (2014) What Do Metrics Want? How Quantification Prescribes Social Interaction on Facebook.Computational Culture. http://computationalculture.net/what-do-metrics-want/. Accessed 19 Sept. 2018.

Prior, Andrew. “Søren Pold and Christian Ulrik Andersen: The Metainterface: The Art of Platforms, Cities and Clouds. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2018.” Leonardo review Archive https://www.leonardo.info/review/2018/09/review-of-the-metainterface-the-art-of-platforms-cities-and-clouds, accessed 21 september 2018

Stanfill, Mel (2015) The interface as discourse: The production of norms through web design. New Media & Society,Vol. 17(7): 1059–1074

Thaler, Richard H. and Sunstein, Cass R. (2008) Nudge : improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. New Haven & London , Yale University Press

Morozov, Evgeny (2013) To save everything click here. The folly of technological solutionism. New York, Public Affairs

Van Dijck, José. (2013) The Culture of Connectivity: A Critical History of Social Media. Oxford: Oxford University Press.