Beyond-viral marketing, Nike just does it again

source: Nike.com

On September 3rd, 2018, Nike released their latest ad campaign to celebrate the 30th anniversary of their iconic ‘Just Do It’ brand. To the surprise of many, former NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick was the face of the campaign. This ad was able to create a moment of mono-culture, a single event of which most Americans were aware. This was an easier feat in the days of mass media, when broadcast programming guaranteed anyone tuning in was receiving the exact same message.

With digital media we have gone back to a model of bespoke media and experience, making it harder for a single event to reach the masses. The Nike ad achieved this by harnessing existing momentum from the controversy surrounding Colin Kaepernick, as well as launching a new meme format.

The Context of Kaepernick

The summer of 2016, directly leading up to Colin Kaepernick’s decision to kneel, was rife with racial tension and clashes between minorities and police- often including the killing of young, unarmed black men. (Roarke, Copeland 86) These events were not isolated to 2016, they also are part of a much larger and complex history in the United States of African Americans, dating back to the founding of the country.

Kaepernick first gained national attention in September 2016 when he began sitting, and then kneeling, during the US national anthem at his NFL games. Kaepernick was clear it was a conscious protest and hoped it would bring attention to issues of racial inequality. Said Kaepernick: “I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of color…To me this is bigger than football and it would be selfish on my part to look the other way.” (Hauser, 2016).

This symbolic gesture quickly spread via social media to other athletes and sports, and opened up a nationwide debate about the appropriateness of his actions. After a season of kneeling and sparking both support and criticism, Kaepernick’s NFL contract was not renewed. His Nike contract, on the other hand, was not only maintained by also renegotiated earlier this year (Abad-Santos)

The Believe in Something Campaign

The ad campaign kicked off with Kaepernick posting a photo to this Instagram campaign. It featured a close up of his face with the phrase “Believe in something, even if it means sacrificing everything.” The post, referencing the sacrifice of his NFL career, has over 1.1 million Likes with over 70 thousand comments. (AVERAGE POST METRICS?) This was quickly followed by an inspirational video ad featuring a diverse array of athletes, finishing on Kaepernick. Other prominent (Nike sponsored) athletes Serena Williams, Lebron James and Odell Beckham Jr. also promoted the campaign over their social media accounts.

The initial response seemed to be divided, with the hashtag #boycottnike trending on social media platforms. (Trending topics happen when many people are discussing the same topic at the same time.) Within the Labour Day weekend, it was clear that the moves to boycott Nike were indeed by offset by the opposition’s decidedly American approach: symbolic consumption. Sales were up 31% (Martinez) and as of the writing of this article, Nike’s market share is up $6 billion (Mosbergen).

Arguing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse on Social Media

One of the standout reasons why this ad performed so well is the inclusion of Kaepernick as a spokesperson. He was guaranteed to evoke many opinions from supporters and detractors; but no matter which side responded, they would be talking about Nike. In 1985, Neil Postman published his famous book “Amusing Ourselves to Death”, in which he observed that television programming wasimpacting public discourse. It was prioritizing short, rapid content over the engaged consumption and discourse of reading and conversation.

Brian L. Ott takes a similar look at social media (Twitter in particular), and concludes that it actually nudges users to be less empathetic, and actually communicate in meaner, more malicious tone. (60) By choosing a provocative spokesman such as Kaepernick, Nike are giving both sides the opportunity to pick a side and engage. It is opinions, not facts, which people tend to post, and they often see the most engagement (Likes, Comments, Retweets) on negative posts. (Tait) Now consider that 67% of US adults are using social media as a news source, and it can make sense why Nike would want an ad which starts passionate conversations on social media.

Memes, A Common Language

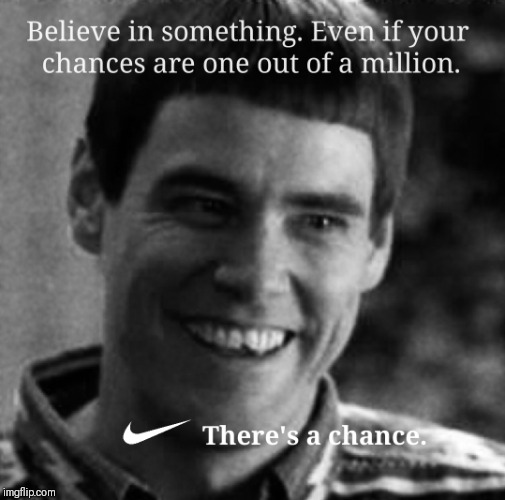

Shifting gears away from the controversial aspect of the ad, Nike actually pulled off an unrelated feat. They were able to not only get people to share their original creative of Kaepernick. Almost instantly, users began creating their own versions “Believe in _______, even if it means _______.” In this way, users stopped perceiving the advertisement as such, but rather a structure to incorporate in their digital communications. This is a little something those in the business (ok, everyone and their mother) call viral content.

Source: Imgflip.com

Considering the true meaning of the word: a virus enters a system by means of disguise, presenting itself as part of the system it wishes to infiltrate. In the human body, it will be genetic material; in computer systems, it will be code. Often advertising will work on the same principal: rely on existing an framework to connect with consumers. Nike flips the script, effectively becoming the script, or in the case of a virus: the host. When people make a meme based on the original, they’re including the assumption that the Nike ad is so prevalent everyone will have seen it. Also, whenever they share their meme versions, they are still posting a “Nike ad”, giving the company earned media as no actual cost.

Conclusion

When considering the noise in advertising today, it can be very rare when an ad holds the attention of so many, even if only for a span of days. The average American sees 4,000 – 10,000 advertisements every day (Marshall), making it very hard for a single ad to captivate a nation. Nike achieved this task by presenting a controversial ad, harnessing existing momentum and creating an ad so iconic that meme satire continued promotion beyond their managed campaign.

References

Abad-Santos, A. “Why the social media boycott over Colin Kaepernick is a win for Nike” (2018) Accessed on 20 September 2018. <https://www.vox.com/2018/9/4/17818162/nike-kaepernick-controversy-face-of-just-do-it>

Hauser, C. “Ruth Bader Ginsburg Calls Colin Kaepernick’s National Anthem Protest ‘Dumb’” (2016) Accessed on 18 September 2018. <http://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/12/us/ruth- bader-ginsburg-calls-colin-kaepernicks-national-anthem-protest-dumb.html

Marshall, R. “How Many Ads Do You See in One Day”. (2015) Red Crow Marketing. Accessed 19 September, 2018. <https://www.redcrowmarketing.com/2015/09/10/many-ads-see-one-day/>

Martinez, G. “Despite Outrage, Nike Sales Increased 31% After Kaepernick Ad”(2018) Time.com. Accessed 20 September, 2018. <http://time.com/5390884/nike-sales-go-up-kaepernick-ad/>

Mosbergen, D. “Nike’s Market Value Surges By $6 Billion After Controversial Kaepernick Ad” (2018) Accessed on 23 September, 2018. <https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/nike-market-value-colin-kaepernick_us_5ba7693ae4b0375f8f9dcb09>

Ott, B. L., “The age of Twitter: Donald J. Trump and the politics of debasement” Critical Studies in Media Communication, (2016) 34:1, 59-68, DOI: 10.1080/15295036.2016.1266686

Postman, N. “Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business”. USA. Penguin, 1985.

Rayport, J., “The Virus of Marketing” (1996) Fast Company. Accessed via digital archives on 19 September, 2018. <http://www.fastcompany.com/magazine/06/virus.html>

Rorke, T., Copeland, A. “Athletic Disobedience: Providing a Context for Analysis of Colin Kaepernick’s Protest”. Revisa de Filosofía, Ética y Derecho del Deporte (2016): page 84-107

Shearer, A., Gottfried, T., “News Use Across Social Media Platforms 2017”. (2017) Journalism.org. Accessed on 19 September, 2018. <http://www.journalism.org/2017/09/07/news-use-across-social-media-platforms-2017/>

Tait, A., “The strange case of Marina Joyce and internet hysteria” (2017) The Guardian. Accessed on 19 September, 2018. <https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/aug/04/marina-joyce-internet- hysteria-witch-hunts-cyberspace?CMP = oth_b-aplnews_d-1>