Free as in ‘labor’, not as in ‘movement’: Google’s Local Guides and Gamifying Digital Maps

In the past few years, tourism has hit an all-time high across the globe. With decreasing costs of transportation and travel, more and more countries are seeing unprecedented numbers of visitors. By May 2018, Turkey had received 11.8 million tourists, a 30% increase from 2017 (Bulovali 2018). With similar statistics in countries everywhere from Japan to Spain, it is safe to say we are in the age of Big Tourism. But who helps all of these visitors find their way around? Google suggests that you do.

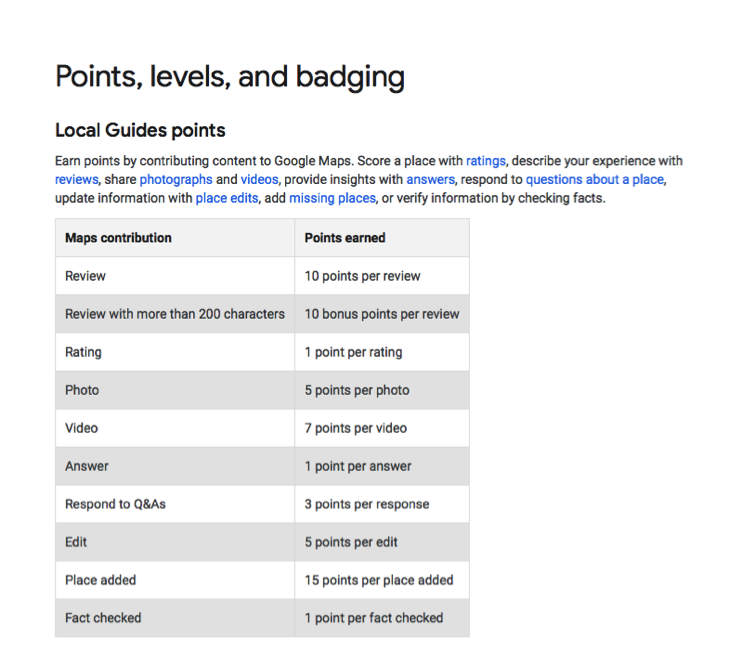

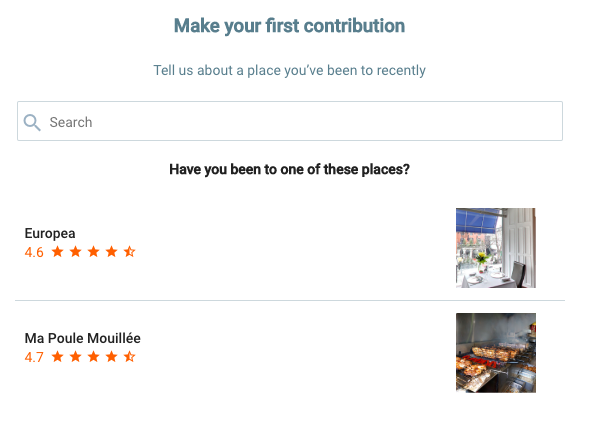

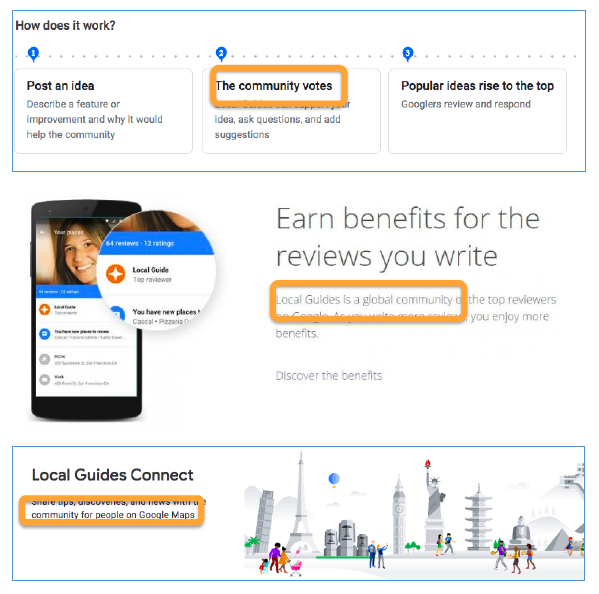

In 2012, Google Maps released ‘Local Guides’, a user contribution program that was gradually expanded worldwide. The goal behind the program was to entice long-time inhabitants of popular destinations to contribute information to Google Maps, allowing first-time visitors to navigate and discover new places easily. The biggest characteristic of the program is its gamified elements: users can earn points by submitting ratings, writing reviews, sharing photographs, and answering questions (Figure 1).

Figure 1 (Local Guides Help)

As users earn more points and reach higher levels, they can even earn certain benefits. For example, at Level 4, Guides are given the Local Guides’ badge. At even higher levels, Guides are offered rewards such as free Google Drive storage upgrades and t-shirts.

Gamification strategies attempt to increase user engagement and ensure continual use of a product by incorporating elements typically found in games (Morozov 203). These elements of game-play, such as point scoring, score keeping, and competition with other users, provide incentives to continue using a particular product for a longer period of time. The gamification of both online and offline experiences has seen a rapid growth over the past few years (Barreneche 345), so it is only natural that it has influenced digital maps as well.

The Local Guides program is Google’s attempt to encourage more people to use their Maps application; it uses rewards and incentives to encourage the contribution of quality content. By gamifying the Maps experience, Google is not only able to crowd-source map data and increase the value of its platform, but also transforms the use of maps and practices of map-making, ultimately exerting control over the way places are navigated, experienced, and made.

Methodology

In this post, we attempt a critical intervention into the gamification of mapping platforms by situating the gamification of Local Guides within the context of academic debates surrounding the politics and governance of location platforms. In our analysis, we use the platform’s interface, policies, forums, and self-promotion in order to investigate its underlying ideologies, and then situate these findings within a larger framework of platform governance and control in order to identify the specific effects gamifying user experience has on the way Google Maps are made and put to work geographically, economically, and politically.

Live to Win: Effects of Pervasive Gamification

As more aspects and areas of our lives are transitioning to online platforms, the technical engineers that design the platforms are becoming social engineers by introducing certain incentives and affordances into daily activities. The concept of affordances indicates what people are able to do with the medium, based on the particular tools and features that are embedded in its architecture (Davis & Chouinard 241). By deciding what users are able to do on a platform, programmers also affect what users can do in the real-world activities that the platform supports. But it doesn’t stop there: the programmers are also able to influence what users want to do by adding incentives through gamification.

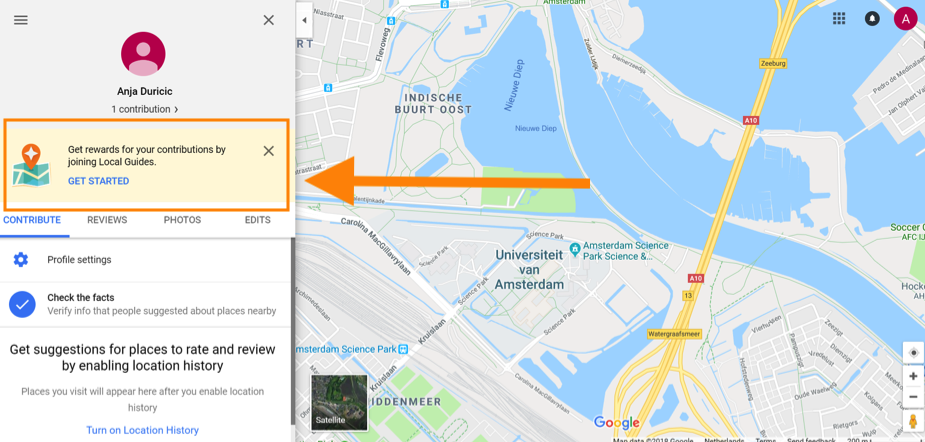

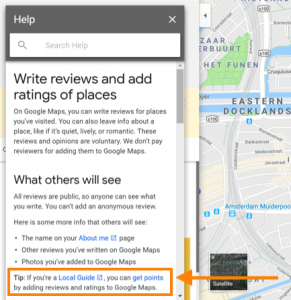

Gamification prompts users to continuously use the platform or service by introducing new incentives into the platform’s activities, such as competition or reward systems, and therefore adds value to participation (Barreneche 344). This trend of gamification offers almost infinite possibilities to programmers, who get to decide which aspects of our daily lives will be rewarded, and so also which are seen as valuable. On Google Maps, gamification is enacted through the affordances provided by the map’s interface. As a regular user of Google Maps, the most prominent message and action on your user profile is an invitation to join Local Guides and ‘Get rewards’ (Figure 2).

Figure 2 (Google Maps)

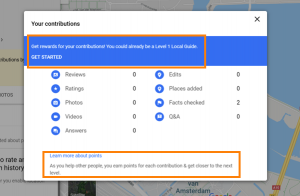

If you continue browsing the options that are offered to you, you are continuously reminded of how far you could get with your points (Figure 3 and 4). These reminders serve as nudges, pushing users into certain actions. ‘Nudging’ is defined as any aspect of the choices that we are presented with “that alter people’s behaviour in a predictable way without forbidding any opinions or significantly changing their economic incentives” (Thaler & Sunstein 6).

Figure 3 (Google Maps)

Figure 4 (Google Maps)

Google Maps nudges users to become Local Guides by posting prominent reminders of the points they could be getting through actions they might already take. Once users become Local Guides, the entire experience is gamified, where each action can earn users different points or badges (Figure 1) and nudges them towards further participation. The gamification of the Local Guides experience can then be seen as creating an environment where the user is constantly motivated to contribute content.

When combined with gamification, nudging can work as an effective tool for businesses to expand their marketing strategies and influence, as it involves subtle motivation, persuasion and manipulation (Sigala 189). Because it has such a strong influence over users, the trend of gamifying maps has raised concerns about who has the power to decide what users are nudged towards, as it may result in the exclusion of smaller retailers that lack the ability or financial resources to partner with Google (Barreneche 346).

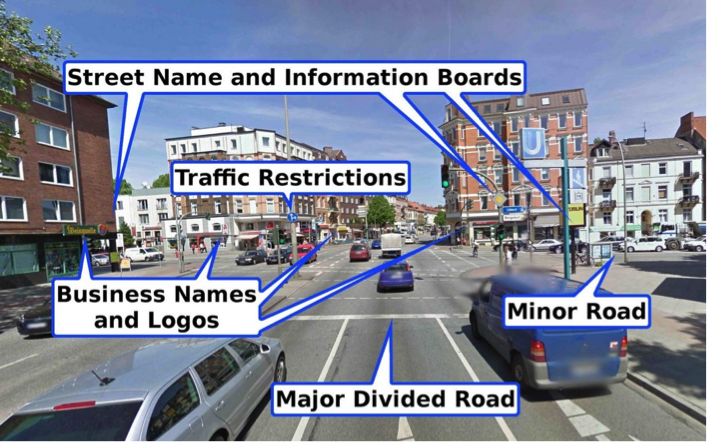

As shown in a 2015 study by Marianna Sigala, recommendations by Google’s Local Guides can heavily impact the decision-making processes of travellers when planning their trip, as user-generated content will resonate more with the users of the platform (192). Ultimately, it is the Google Maps platform that nudges Local Guides to review certain locations by making suggestions to Guides based on user history, the Georeferences ranking system (which ranks locations based on inbound references), and user location (Barreneche 335-336) (Figure 5).

Figure 5 (Local Guides Help)

The gamified nudging of Local Guides therefore shapes socio-economic relationships by determining what places are reviewed and represented on the platform.

Moreover, gamification poses the danger of distracting people from the initial purpose of the product, system, or platform (Hyrynsalmi at al. 5). This can be seen in the changing nature of maps as they are increasingly being used for marketing and advertising purposes. Although Local Guides does allow users to contribute, Google Maps is still not a user-generated platform. Businesses can still buy advertising space in the local search results or even on the map itself, which allow them to become more visible, and leads to more reviews, and more visits (Sigala 192).

Additionally, Hyrynsalmi et al. warn that gamification might replace intrinsic motivations with extrinsic ones (5). In the case of Google’s Local Guides, users may not be driven to contribute to the platform in order to help others navigate their environment, but rather to collect points and badges for the sake of ranking and competition. Hyrynsalmi et al. also argue that constant nudging and reminders to contribute to the platform in return for perks infringes on users’ autonomy (7). By offering benefits such as Google Drive storage or early access to new features (Points, Levels, and Badging – Local Guides Help), Local Guides are encouraged to constantly share their experiences on the platform, compete with other users, and add value to the platform through their contribution. In creating a user-position that is always motivated to create content, Google Maps obscures the free digital labor done by the Local Guides of collecting, refining, and verifying map details, and also makes Guides easier to manipulate by controlling their incentives.

Gamification, Representation and Control

Just as visualizations of data invite particular ways of seeing and knowing (Gray et al. 227), a map’s particular representations invite a particular way of knowing and experiencing a place. By understanding that “technology is not neutral, but rather a mediating and productive force,” (Bucher 480) we can begin to see how Google Maps, as an increasingly primary mechanism through which users encounter their environment, monopolizes the ways that environments are imagined and navigated. Google Maps becomes an “active participant,” (Bucher 482) in shaping the ways we think about and navigate a place. The Local Guides program’s interface and language demonstrate the way gamified digital maps alter how a user thinks about and encounters a place, and how these actions are guided and limited by the software and its underlying ideologies.

Figure 8 (Local Guides Forum)

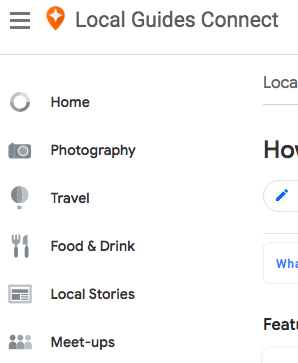

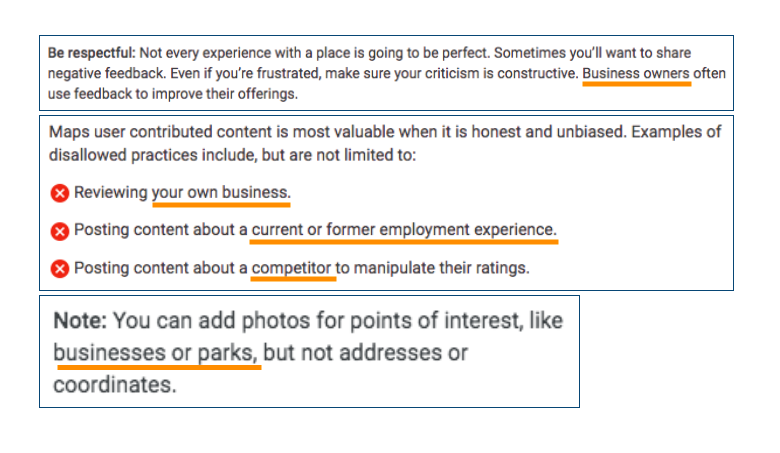

The top three action buttons on the homepage of the Local Guides forum (Figure 6)—Photography, Travel, Food & Drink—indicate what Google Maps believes the ideal Guide should be concerned with, and nudge Guides into focusing on these categories through visual hierarchy. Guides should review restaurants, cafés, bars, and tourist attractions, and should also be aware of the photogenic quality of a place. Featured ‘How-To’ articles like “How to help others find the perfect slice,” and “How to write travel guides of your city using lists,” along with the business-oriented language of the Local Guides’ policy (Figure 7) direct Guides’ collection of data towards consumerism, tourism, and entertainment.

Figure 7 (Local Guides Help)

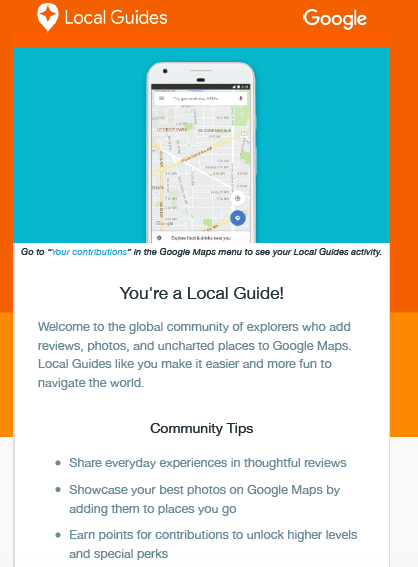

By emphasizing these kinds of activities, Google Maps not only defines the role of Guides, but also indicates the role of maps. Google’s Maps don’t just help users navigate; they conduct, support, and accentuate the flow of consumer activities. This shift in map purpose comes from the separation of Local Guides from regular maps users, and the asymmetrical implementation of gamification and rewards. Local Guides already know where they are going; they use Google Maps for “thoughtful reviews,” sharing photos, and earning points (Figure 8)—not to search for information, read reviews, or navigate.

Figure 8 (Local Guides Introductory Email)

Because they would otherwise not need Google Maps (being ‘local’ to their environment), Guides need to be rewarded for participation with points and badges. Regular users don’t need to be rewarded in the same way, because the map is reward enough—a landscape of sites for consumption, made visible by the labor of the Local Guides.

Google’s Map is one made for the tourist, and accordingly encourages users to see their environment as consumable: a collection of places to eat, pictures to take, spots to visit, and points to earn before moving on—the Maps algorithm will never suggest that a Guide review or visit the same place twice. As Lev Manovich indicates, software limits the available forms of being for users (32). On Google Maps, the available user positions are limited to the Guide, the Tourist, and the Point of Sale, all encouraged to see their environment as a place to mine for undiscovered value. Because Google Maps is the platform by which users access and create this value, all user actions on work to augment the overall value of the platform (Barreneche 340-341).

By sorting and classifying users based on their actions, Google Maps can then create “processes of identification that structure and regulate our lives,” (Cheney-Lippold 166), which make users cohere to the behavioral parameters of their chosen user-position, effectively controlling their actions. For example, the Local Guides platform emphasizes that the Guide is part of a “global community” (Figure 9) and that community is a central part of the Guide-identity.

Figure 9 (Local Guides Connect)

This community is, however, provided, accessed and maintained by Google. The ‘Meet-ups’ page on the forum is an approved community affordance made by the software, whereas listing a friend’s home address and contact information (common on paper maps) would be in violation of Google policy (Local Guides Help). In defining the user-identity of ‘Local Guide’ as community-driven and then controlling appropriate ways of being within the community, Google contains and regulates user actions so that they perpetuate forms of map- and place-making that maintain Google Maps’ authority.

The Mapped Economy: Digital Labor, Presence, and Economic Viability

No matter how advanced, the current reality of digital maps is that “satellites and algorithms only get you so far” (Miller, 2014). Though Miller notes that Google has long employed a small army of human operators to manually check and correct its maps, initiatives such as Local Guides increase this workforce by several orders of magnitude, equally increasing the available stores of low-cost environmental data.

This new workforce is important because algorithms are prone to mistakes. The qualitative data provided by Guides allows Google to both enhance the reliability and authenticity of its platform, and keep training its algorithms. In the world of online maps, accuracy is value, so it is in Google’s best interest to be as accurate as possible.

One partnership that similarly allows Google to increase its accuracy—and therefore user-trust and user-base—is with Pokemon GO, a mobile gaming application designed by Niantic. Pokemon GO is a part of the process through which “Google manages to set up a circuit of database coproduction that continuously feeds back into a cycle of production as the data contributed by users makes Google’s place database more valuable” (Barreneche, 343).

Pokemon GO users, like Local Guides, constantly generate data for Google Maps by interacting with gamified maps. Like Local Guides, Pokemon GO also introduces gamified elements into digital maps in order to influence user navigation and maximize profits through partnerships with local retailers and increased user participation. Because the game is the overwhelming focus of Pokemon GO (rather than the map), the data mining that users do is much less explicit, allowing for direct partnerships that don’t rely on user contribution or reviews to attract consumers.

Niantic’s revenue from sponsorships provides an extreme example of the power of direct advertising already possible through Google Maps. McDonalds Japan received 500,000,000 visitors as a direct result of a Pokemon Go Partnership, paying Niantic $0.15-$0.50 per visitor brought in by a Pokemon GO incentive placed in their stores (Constine, 2017). The pay-per-visitor model is functionally identical to Google’s pay-per-click, but Pokemon GO differs from Google Maps in that it has a monopoly on players, and so total control of their gaming incentives. This monopoly allows Pokemon GO to directly choose which places are visited, seen, and experienced by controlling their value through digital rewards and incentives. These digital rewards also obscure the reality that the users are doing all of this labor for free.

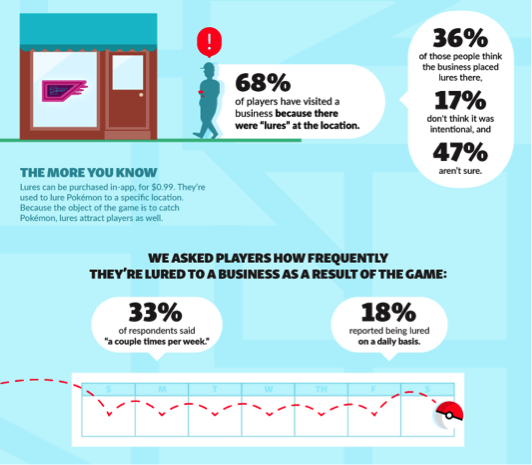

After surveying 500 Pokemon GO players, the PR firm Slant generated multiple infographics that visualize the app’s incredible influence over consumer behavior and economic trends (Figure 10 & 11).

Figure 10 (Marketing Resources Incorporated, “What Pokemon Go Could mean for your business)

Figure 11 (Marketing Resources Incorporated, “What Pokemon Go Could mean for your business)

Partnering with Pokemon Go enabled McDonalds Japan to incentivize 500 million new visits to its stores. Assuming an average expenditure of $11.30 per visitor (Slant, “Catching Customers”), McDonalds Japan would have generated a profit margin of at least 95%—an unbelievable incentive to partner with the app. Both McDonalds Japan and Pokemon GO were able to derive incredible economic capital from the gamified labor of users. This example represents the kind of power that gamification alone can have on consumer behavior when applied to digital maps, and exemplifies the kind of work that Local Guides is doing. However, Google Maps goes one step further.

The more Local Guides contribute to Google Maps, the more accurate and believable the platform becomes. Because of its primary function as a map, the more accurate and believable the representation is, the more users will turn to the platform for their directions. Once it has a monopoly on users, Google Maps will become the primary way all users access the world, “the underlying database” (Barreneche 343) of reality. But the gamification of the Local Guides platform indicates that this monopoly isn’t just navigational, it’s economic, “This model entails a database economy whereby value is extracted out of the collection and mining of the data produced in Google’s different services,” (Barreneche 343). Being visible on Google Maps will become fundamental to economic existence. With heavy profit incentives and a risk of economic exclusion, no business will be viable unless visible on the platform.

Gamification has led to a repurposing of mapping platforms. While maps before were seen as a tool to get from one place to another, today maps have become entire experiences unto themselves, constantly keeping users engaged and generating value. By gamifying the user experience, Local Guides seeks to control user behavior and navigation, while increasing the value of the Google Maps platform through incentivized digital labor. With enough users, Google Maps has the potential to become the underlying platform of the economic world, commodifying online visibility and controlling access to both consumers and retailers, thereby becoming the “obligatory intermediary” (Barreneche 342) of all economic activity.

As tourism surges worldwide, it is important to notice the ways in which visitors are guided through their destinations: is it really by locals? Or is it by Google Maps? Where are they being guided? Who profits off their movement? As more of the worlds populations are mobilized, these questions become critically important in determining the economic power of a platform like Google Maps.

Contributors: Eliza Connolly, Anja Duricic, Sohini Goswami, Tim Groot

Sources

Barreneche, Carlos. “Governing the Geocoded World: Environmentality and the Politics of Location Platforms.” Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, vol. 18, no. 3, 2012, pp. 331–51, doi:10.1177/1354856512442764.

Brown, Ben. “The Psychology of Gamification in 2016: Why It Works (& How To Do It!).” Bitcatcha – Online Presence DIY, 2 Aug. 2016, https://www.bitcatcha.com/blog/gamify-website-increase-engagement/.

Bucher, Taina. “The Friendship Assemblage: Investigating Programmed Sociality on Facebook.” Television & New Media, vol. 14, no. 6, 2012, pp. 479–93, doi:10.1177/1527476412452800.

Bulovali, Aise Humeyra. “Turkey Hosts 11.8M Tourists in First 5 Months of 2018.” Anadolu Agency, 21 June 2018, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/culture-and-art/turkey-hosts-118m-tourists-in-first-5-months-of-2018/1181653.

Cheney-Lippold, John. “New Algorithmic Identity: Soft Biopolitics and the Modulation of Control.” Theory Culture Society, vol. 28, no. 6, 2011, pp. 164–81, doi:10.1177/0263276411424420.

Constine, Josh. “Pokémon GO Reveals Sponsors like McDonald’s Pay It up to $0.50 per Visitor.” TechCrunch, http://social.techcrunch.com/2017/05/31/pokemon-go-sponsorship-price/. Accessed 9 Oct. 2018.

Davis, Jenny L., and James B. Chouinard. “Theorizing Affordances: From Request to Refuse.” Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, vol. 36, no. 4, Dec. 2016, pp. 241–48. Crossref, doi:10.1177/0270467617714944.

Garcia, Stephen M., et al. “The Psychology of Competition: A Social Comparison Perspective.” Perspectives on Psychological Science, vol. 8, no. 6, Nov. 2013, pp. 634–50. SAGE Journals, doi:10.1177/1745691613504114.

Google Ads Help. About Local Search Ads. 2018.

Gray, Jonathan, et al. “Ways of Seeing Data: Toward a Critical Literacy for Data Visualizations as Research Objects and Research Devices.” Innovative Methods in Media and Communication Research, Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.

Hyrynsalmi, Sami, et al. The Dark Side of Gamification: How We Should Stop Worrying and Study Also the Negative Impacts of Bringing Game Design Elements to Everywhere. 2017, p. 9.

“Local Guides – Google’s Gamification Strategy to Crowd Source Maps Data.” Free Review Monitoring, 19 Nov. 2015, http://blog.freereviewmonitoring.com/local-guides-googles-gamification-strategy-to-crowd-source-maps-data/.

Local Guides Help. Community Policy. 2018, https://support.google.com/local-guides/answer/7358351?hl=en.

Manovich, Lev. “Media After Software.” Journal of Visual Culture, vol. 12, no. 1, 2013, pp. 30–37, doi:10.1177/1470412912470237.

Miller, Greg. “The Huge, Unseen Operation Behind the Accuracy of Google Maps.” Wired, Dec. 2014. www.wired.com, https://www.wired.com/2014/12/google-maps-ground-truth/.

Morozov, Evgeny. “Gamify or Die.” To Save Everything, Click Here: The Folly of Technological Solutionism, Public Affairs, pp. 203–05.

MRI editor, Inc. “Pokémon Go Creates New Customers for Businesses.” Marketing Resources, Inc., 9 Aug. 2016, https://marketingresources.com/pokemon-go-mean-business/.

Points, Levels, and Badging – Local Guides Help. https://support.google.com/local-guides/answer/6225851?hl=en. Accessed 2 Oct. 2018.

Sigala, Marianna. “The Application and Impact of Gamification Funware on Trip Planning and Experiences: The Case of TripAdvisor’s Funware | SpringerLink.” Springer Berlin Heidelberg, vol. 25, no. 3, Jan. 2015, pp. 189–209, doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-014-0179-1.

Thaler, Richard, and Cass Sunstein. Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness. Yale University Press, 2008.