EcoScanner: Self-tracking Sustainability

Piloting the EcoScanner: A Self-tracking Solution to Sustainability

Annika Heinemeyer, Daniel Jurg, Molly Doell, Ziwen Tang

Abstract

|

Introduction

There are two main trends observable in our contemporary society. First, topics like sustainability, environmental protection, and green products are becoming more ubiquitous. Research has shown that green products claiming to be “sustainable”, “environmentally friendly”, or “eco-friendly” have become ‘cool’ in today’s society (Ottman 13, Dangelico and Pujari 471). According to Ottmann (XIX), these changes rely primarily on the association of green products with values like better health, superior performance, good taste, and cost-effectiveness. Secondly, people are using their smartphones and mobile applications for almost every daily activity. People use ‘self-tracking’ devices and mobile applications to track their behavior and accomplishments regarding health, fitness, personal mobility, and wellbeing. These self-tracking apps are created to nudge people into better and more healthy decision making by creating a technically produced self-awareness (Pomputius 178; Jethani 41).

Taking the aforementioned trends into consideration, one could ask why people track most activities of their lives but not their behavior regarding sustainability. This blog post proposes an intervention into the sustainability market drawing on the self-tracking trend: the EcoScanner. This blogpost then (1) situates this intervention within current academic debates, (2) establishes a methodology to operationalize the project, (3) presents the current and future sociability and design of EcoScanner, and finally (4) critically analyzes the possible shortcomings of this intervention.

New Media and the Green Market

In The New Rules of Green Marketing: Strategies, Tools and Inspiration for Sustainable Branding, Ottman sets out new digital strategies to engage green consumers and stimulate the purchase of sustainable products. Using new media to engage consumers in shopping behavior can be observed in the self-scanning technology in supermarkets, for example. It is quick and easy, and gives consumers the feeling of “more control” about their goods and spending (D’Innocenzio n.p.). Opening up to the question: Why not try to give consumers even more control, or awareness as a start, of their sustainable habits?

There are multiple ways for consumers to take more control of their in-store shopping experiences. Customers can download apps of the supermarkets, look at the prices, and process to checkout. The deployment of self-scanner machines also contributes to the convenience of the shopping process. We propose with easily accessible information and nudges, these behaviors could be extended to include concerns around waste and sustainability. Several apps were made to address this, including OpenLabel and GoodGuide (Cheeseman n.p.). However, switching between apps and devices makes the experience complicated and clunky. A main problem for these mobile applications is that they focus on the interaction with consumers, leaving the producers out. Cheeseman (n.p.) argues that as a result, it is unclear to what extent consumers’ decisions can efficiently change the production lines. For instance, CodeCheck is an existing application developed in 2017, providing information about ingredients and additives in food or cosmetics (Apple Store: CodeCheck). However, the functionalities are not directly integrated into the purchasing process and rely primarily on people’s individual motivation to use them (Atkinson 391). Consequently, a new functionality is needed that engages consumer and trade companies and relies on already established behavior.

As a pilot, we propose Albert Heijn, the large, sustainability-oriented Dutch grocery store to launch a functionality to track basic waste from packaging on goods sold in their store. This function could be integrated with their self-scanner and shopping app; providing a sustainability report to customers in form of a colored icon. In addition to providing general information about wastage, the functionality could nudge people to purchase products that are more sustainable. Simultaneously, our intervention would not only nudge the consumer, but also eventually to motivate producers to develop more environmental-friendly materials and production methods. In the long run, it could be developed into a more robust and complex solution based on the preliminary experiences with the initial function.

To assure that our EcoScanner is appealing and is conveyed in an understandable manner to consumers, mechanisms of gamification will be incorporated. Game incentives, like rewards, scores and levels, have motivational impacts on consumer behaviors (Deterding 28). In light of this, EcoScanner will use game technologies to maximize impact and engagement on our environment. As Marc Pincus, CEO of Zynga that produced for example the Facebook-Game FarmVille, said: “Games should do good. We want to help the world while doing our job” (qtd. in Morozov 204).

Methodology

In order to operationalize our pilot, we turn to Chohan et. al., who in their paper “A Methodology to Develop a Mobile Application Model to Appraise Housing Design Quality” set out a methodological structure in order to establish an app rating the quality of housing design. The EcoScanner project draws on the same methodology, appropriating it to track waste generated when buying groceries. Chohan et. al. (9-13) distinguish three stages in creating an app: (1) Data Collection, (2) Data Flow and (3) Mobile Application Development.

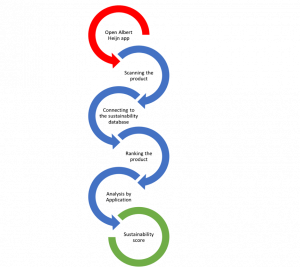

The first stage is to set-up a good database structure for measuring sustainability. We will not build this data-base ourselves, but draw from Eurostat, the statistical office of the European Union. It “offers a whole range of important and interesting data that governments, businesses, the education sector, journalists and the public can use for their work and daily life” (Eurostat n.p.). At the start, the EcoScanner will focus on sustainable packaging, but while this database forms an important start of the project it will be necessary to extend this focus in the future. It might be useful to look at other factors in the future such as production and transportation, for example. In the second stage the “available data will be reviewed in the context of quality indicators” (Chohan et. al. 10). Eurostat proposes six waste categories to measure sustainability in order to come up with a sustainability score: (C1) Paper and cardboard packaging, (C2) Plastic packaging, (C3) Wooden packaging, (C4) Metallic packaging, (C5) Glass packaging, and (C6) Other packaging (Eurostat n.p.).

The final stage is the actual development of the application. This stage is subdivided in seven phases of development: (D1) Application planning, (D2) Application needs, (D3) Application design and sociability, (D4) Application development, (D5) Application Testing, (D6) Application Security & Privacy, and (D7) Application Analysis. The first two steps of the development have already been addressed so far, setting out the context of the EcoScanner and the need for a database. Our project limits its scope to the theoretical planning of the EcoScanner, meaning that the phases D4, D5, and D6 will be outsourced. Our blog will go deeper into the design and sociability and will close with a critical analysis of our intervention.

Design and Sociability

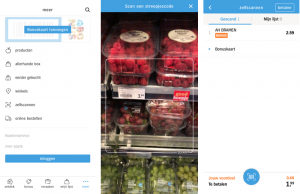

Our intervention is applied to two media platforms, the AH mobile app and its in-store self-scanners. Both media afford consumers the ability of scanning products, and therefore when people scan the products in supermarkets, the sustainability database would rank the products based on the six categories by Eurostat (n. p.), and then it gives each product a score from 0 to 100. Here, 0 represents the worst to sustainability, and 100 means the optimal score.

Diagram 1: Data flow in our project

For better visualization and due to limited space on the screens, we would then use a colored sustainability icon to represent the score: red, yellow and green. Correspondingly, these colors respectively refer to a bad, moderate, and good sustainable purchase. The icon will be displayed next to the price after one product is scanned either on the app or self-scanners.

![]()

Figure 1: Colored icons for sustainability

We want to pilot our EcoScanner on two different media: (1) the Albert Heijn Application and (2) the self-scanning machines. As can be seen on figure 2, the interface only displays the information of product names and prices. Without a dramatic change, our project adds an icon besides the price, showing customers the sustainability of the scanned product. At the bottom where the sum total lists, we also give consumers an overall colored icon of their scanned products. Furthermore, instead of shaming the consumer, we use positive and encouraging phrases to compliment and gamify their contribution to sustainability (Deterding 28). The ‘green’ icon will say to people ‘great job’, the ‘yellow’ calls to ‘keep going’, and the ‘red’ icon indicates that the consumer ‘has room for sustainability’. The added sustainability information intervenes in the purchasing process, stimulating the consumers’ focus on nutrition and prices, and encourages people to pay more attention to social responsibility. Figure 3 visualizes these changes.

Figure 2: The current interface of self-scanning function in Albert Heijn app

Figure 3: New interface of self-scanning function in Albert Heijn app with intervention

Figure 4: Current interface of AH self-scanner

Figure 5: New interface of a self-scanner in AH stores through our intervention

The second medium we intervene in is the in-store self-scanner machines (Figure 4). The infrastructure of self-scanners has currently been employed in 240 AH-stores in the Netherlands, of which 88 are located in Amsterdam (Albert Heijn n.p.). The scanner functions in a similar way as the self-scanning app. Consumers will obtain not only the prices, but also the packaging waste information about the scanned products (Figure 5).

Assuming that this project will be widely accepted by both the store and the consumer, we imagine the following roadmap of adding more appealing elements to the EcoScanner:

- Implementing waste values into the function of recipes (Dutch: recepten) of the AH app. Albert Heijn app already includes the recepten function, listing every ingredient you need for a recommended nice dinner. At the end of each recipe page, it shows nutritional values (voedingswaarden). In the future, the waste value of each recipe can become one of the crucial indicators affecting people’s eating habits and shopping behavior.

- Implementing waste values into online grocery shopping. Being aware of the online groceries shopping trend we want to make the packaging waste values available on shopping websites. As a consequence, we can extend the market for people who use the logo to make sustainable decisions.

- Sharing waste values on social media platforms. Like the other self-tracking apps, we would like to insert the function of sharing people’s waste values upon their grocery shopping on social media. The application of gamification can be optimized on this step, and hopefully this tracking function becomes one of the mediated essentials in everyday life.

Critical analysis

While we would love to solve immediately address all aspects of sustainability with the introduction of EcoScanner, unfortunately we will also need to anticipate a few limitations. Not everyone shopping at Albert Heijn will be in the position to choose products based solely on sustainability. And what is more, some consumers may lack specific expertise when weighing purchasing decisions, making choices more like guesses (Thaler et. al. 9). EcoScanner aims to educate and nudge, but the first version will give context solely on waste reduction. In this final section we address three main concerns: (1) the limits of sustainable packaging, (2) exclusion of consumers, and (3) predicting future behavior.

Firstly, our initial offering in no way accounts for the health or sustainability of the contents within the packaging. A donut from the bakery might appear a ‘sustainable’ choice due to its minimal packaging. However, this could actually be a harmful option for a diabetic (or anyone, given your stance on sugary treats). Beyond health, we also do not currently rank sustainability of ingredients. Palm oil for instance, a prevalent staple found in roughly half of all supermarket products (Sandhu, n.p.) is also a contributor to deforestation in Indonesia. As EcoScanner develops, we would like to include deeper ethical context and sustainable details for each product.

Secondly, with the broad range of shoppers at Albert Heijn, we recognize not all will be in a position to make decisions based solely on sustainability. 4 in 5 Consumers think Eco-Friendly products cost more (PRNewswire, n.p.) making this an immediate barrier to attract anyone concerned foremost with price. Another group which we would not like to shame or isolate are those who require increased packaging. Whole Foods pulled peeled and packaged oranges following an outcry on Twitter. While a win for sustainability, this did not take into account people who lack fine motor skills to peel and orange.

It is never our aim to shame or isolate those who are not in a position to make sustainable choices, financially or otherwise. In order to make this more accessible to all incomes and desired investment, we propose discounts and financial incentives to motivate and offset the effort. Additionally, in our roadmap we intend to advocate producers to improve/reduce packaging, at no increased cost to consumers.

And finally, EcoScanner is developed according to the way which people have been buying groceries and not to the way which they will be. Often in media, societies have look at new environment through the lens of the old one. (McLuhan 96). Our project has foundations in a declining shopping model: physically going to the store and collecting food from various aisles.

Around two million Dutch residences shopped online for groceries in 2017, a 20% increase from 2016, according to ECommerce News. If this trend continues, as we expect it will, we propose future iterations should consider machine learning to apply the rich Albert Heijn data to promote sustainability. Targeting capabilities, profile of sustainable shoppers and hypernudge recommendations could all be included in an shopping application.

Conclusion

Our project envisages a future in which the technological capabilities of self-tracking apps converge with a sustainable mindset. Our EcoScanner sets itself apart from existing suitability trackers by intervening directly in the purchasing behavior of the consumer nudging both consumer and producer. By visualizing a sustainability score on the existing self-scanner and AH app, we want to make the consumer aware of her consumption before the purchase. However, while the EcoScanner might provide the consumer with access to more sustainable information, it is the consumer herself that in the end has to make the sustainable decisions. It is our hope that the blog about our pilot will not read as a future solution to a current problem. If any, it is hopefully a first step in creating consumer awareness, paving the way to scan ourselves to a more sustainable market.

References

Atkinson, Lucy. “Smart shoppers? Using QR codes and ‘green’ smartphone apps to mobilize sustainable consumption in the retail environment.” International Journal of Consumer Studies 37.4 (2013): 387-393. Wiley Online Library, <10.1111/ijcs.12025>. Accessed 22nd October 2018.

Cheeseman, Gina-Marie. “Bar Codes Apps allow Consumers to make informed Choices.” Triple Pundit, 25.April 2012,

<https://www.triplepundit.com/2012/04/bar-codes-apps-allow-socially-conscious-consumers-make-informed-choices/>. Accessed 21st October 2018.

Chohan et. Al. “A Methodology to Develop a Mobile Application Model to Appraise Housing Design Quality.” International Journal of Interactive Mobile Technologies. 11.6 (2017): 4-17.

Dangelico, Rosa Maria and Devashish, Pujari. “Mainstreaming Green Product Innovation: Why and How Companies Integrate Environmental Sustainability.” Journal of Business Ethics 95 (2010): 471–486.

Deterding, Sebastian. “The Ambiguity of Games: Histories and Discourses of a Gameful World.” The Gameful World: Approaches, Issues, Applications, by Steffen P. Walz and Sebastian Deterding, The MIT Press, 2014, 23–64.

D’Innocenzio, Anne. Why Scan-and-Go Technology Is Surging in More Grocery Stores. Inc., 23.February 2018, <https://www.inc.com/associated-press/supermarket-chain-stores-new-technology-scan-go-customers-amazon-phone-app.html>. Accessed 21st October 2018.

Earl, Jennifer. “Whole Foods responds to $6 pre-peeled orange Twitterstorm” CBS News, <www.cbsnews.com/news/whole-foods-responds-to-6-pre-peeled-orange-twitterstorm/>. Accessed 12th October 2018.

Eurostat. “Packaging waste by waste management operations and waste flow.” 18 August 2017. <https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cache/metadata/en/env_waspac_esms.htm>. Accessed 15th October 2018.

Fogg, B.J. Persuasive Technology Using Computers to Change What We Think and Do. San Francisco: Morgan Kaufmann Publishers, 2003.

Jethani, Suneel. “Mediating the Body – technology, politics and epistemologies of self.” Communication, Politics & Culture 47.3 (2015): 34-43.

McLuhan, Marshall. “The Emperor’s Old Clothes.” The Man-Made Object. Ed. Georgy Kepes. New York: George Braziller, 1966. 90-95.

Morozov, Evegeny. To save everything, click here. New York: Public Affairs, 2013.

Ottman, Jaquelyn A. The New Rules of Green Marketing: Strategies, Tools and Inspiration for Sustainable Branding. Oakland, California: Berrett-Koehler, 2011.

Pomputius, Ariel F. “Mind over Matter: Using Technology to Improve Wellness.” Medical Reference Services Quarterly 37. 2 (2018): 177-183.

Sandhu, Serina. “What is Palm Oil and why is it so bad for the environment?” iNews, <www.inews.co.uk/news/environment/what-is-palm-oil-why-so-bad/>. Accessed 12th October 2018.

Thaler, Richard H. and Cass R. Sunstein. Nudge : improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. London: Penguin Putnam Inc, 2008.

“AH Zelfscannen.” Albert Heijn, 2018, <https://www.ah.nl/winkels>. Accessed 20th October 2018.

“4 in 5 Consumers Think Eco-Friendly Products Cost More ‘Green’” PRNewswire, 7th April 2015, <www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/4-in-5-consumers-think-eco-friendly-products-cost-more-green-300061649.html>. Accessed 20th October 2018.

“1 in 6 Dutch will order groceries online in 2017” Ecommerce News Europe, 26th September 2016, <www.ecommercenews.eu/1-6-dutch-will-order-groceries-online-2017/>. Accessed 20th October 2018.

Images

Figure 2: Screenshots of Albert Heijn app. The current interface of self-scanning function in Albert Heijn app. 2018. 17 October 2018.

Figure 3: Screenshot of Albert Heijn app. New interface of self-scanning function in Albert Heijn app with intervention. 2018. 17 October 2018.

Figure 4: Kunde, Dirk. Current interface of a self-scanner in AH stores. 2018. 17 October 2018. <https://www.captain-gadget.de/supermarkt-einkauf-scannen/>.

Figure 5: Picture of Albert Heijn self-scanner and mock-up design. New interface of a self-scanner in AH stores through our intervention. 2018. 17 October 2018.