Swiping Right vs. Finding Mr. Right: Facebook Attempts to Reinvent Online Dating

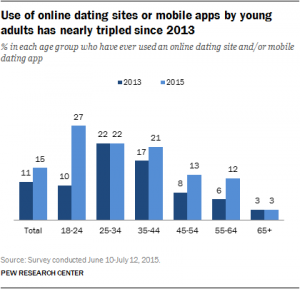

Online dating is becoming an integral part of how people meet each other. According to Pew Research Center, nearly all age groups show a higher percentage of usage of online dating in 2015 compared to 2013 (Smith and Anderson n.pag.).

Figure 1: Usage of Dating Sites and Apps

Additionally, it seems acceptance of this type of dating is also growing (Smith and Anderson n.pag.). Although these studies were conducted three years ago, there are sufficient clues that it is still a trend, as new dating apps continue to enter the scene. Facebook is an influential social media platform, on which the concept of friendship is already being reconfigured (Bucher 485). The following project is about how Facebook Dating may shape discourses around online dating.

At the time of writing, the feature is not yet launched globally, but only in Colombia (Wolverton n.pag.). Nathan Sharp, Facebook Dating´s product manager, claims that they chose Colombia for the testing round because online dating is culturally accepted and data feedback can be given faster since a high percentage of the population is using dating apps daily (Constine n.pag.). As this project is done in the Netherlands, we have used a VPN that situates our network activity in Colombia to be able to access the feature through a fake account. It allowed us to analyze its affordances and high-level affordances (Bucher and Helmond 12) or discourses (Stanfill 1061) the different actors together constitute. Consequently, this project is based on the idea that multiple actors contribute to and shape research of digital artifacts (Marres 146).

Firstly, we will discuss why our project is relevant by situating it in current academic debates. This literature is found using google scholar, but also the university library as these sources can have different literature that is deemed ‘relevant’ by both institutions (Van Dijck 5). This literature study later helps us in our case study, as it provides the necessary framework. Secondly, a short interface analysis is given of Tinder, one of the world’s leading dating apps, to subsequently compare this standard to the upcoming feature of Facebook. Afterward, we will discuss how Facebook has promoted this feature by doing a discourse-analysis of promotional and press material. Lastly, a discursive interface analysis of ‘Facebook Dating’ in beta-testing mode is conducted, to see how the ‘vision’ (Light et al. 9) of Facebook found in the discourse analysis of surrounding material compares to the actual interface.

Facebook´s Steps to Having a Dating Feature

App development goes through countless amounts of steps such as research, wireframing, design and final deployment. Facebook did not introduce their ‘Facebook Dating’ feature out of the blue. Facebook discovered that users already connected romantically (F8 2018 Day 1 Keynote), without the platform explicitly encouraging this process through its affordances (Davis and Chouinard 243). Facebook then decided to design a new feature. This shows how digital content, in the time of constant change, includes aspects of user feedback and creative participation. Many steps are needed to find the winning formula. Facebook Dating is currently in its testing phase where the goal is to identify how users interact and adapt to it, thereby mutually shaping its affordances. This is then used to improve the product before it launches globally (Ashwini n.pag.).

Why Facebook Might Lead the Dating Industry

The most significant advantage that Facebook has over the other already existing dating apps is access to an established user base. On the one hand, there is Tinder with 50 million users per month and on the other hand is Facebook with two billion users, 200 million of whom indicate to be single (Martin n.pag.). This may result in an effect of generative entrenchment (Bratton 47), since these users have already invested their time and energy in Facebook, thus making it easier to use Facebook for dating purposes as well. In the business of online dating, companies try to make it as comfortable as possible for people to engage with a new feature (Carman and Newton n.pag.). As Toma contends, “Facebook has become a one-stop shop for […] informational, social, and romantic needs” (424).

Moreover, by utilizing the trove of data it already has about users, it can generate matches on the basis of this data. To sum up, the company can reduce the startup costs and avail their widespread accessibility for their benefit. All this gives Facebook the ability to become a powerful competitor to other dating apps. While many dating apps have relied on Facebook data for years, such as Tinder, they have never been able to leverage everything.

Another huge advantage Facebook Dating has is that most of the people have registered on Facebook with their real name, gender, and age since they want to connect to friends and give them the opportunity to find them easily on the platform (Sengupta and Chaturvedi n.p.). Obviously, there is a downside as well. The aspiration for love on such platforms usually goes along with “scams, loss of privacy, and public shaming” (Toma 423) and that opens up another interesting debate that is not going to be touched upon further in this project.

Here our focus is on how the environment of Facebook may shape and enable a new process of online dating. To be able to do this, this project first analyzes the interface of Tinder. This discursive interface analysis is being used as the standard which Facebook tries to change, as will be clear from the discourse analysis of promotional and press material. This project will compare Tinder and Facebook and analyze the differences in how the platforms afford different kinds of actions to attempt to ‘capture’ dating.

Tinder: Gamified Dating

Launched in 2012, Tinder became a popular application among young people (numera.com). In 2015, the application already counted more than a billion swipes daily according to figures released at a conference on the annual results of IAC. The application is intuitive and easy to use: swipe right if you like a profile, left if you do not. If two people liked each other’s profile, it is a match. The conversation can start via messages and can, perhaps, lead to a date. It is essential to keep in mind that as users log in to Tinder via Facebook, all the data used by the dating app are coming from Facebook.

Tinder Interface

Tinder’s swipe interface encourages (Davis and Chouinard 243) users to review lots of profiles and offers the freedom to pursue numerous relationship initiations simultaneously. In comparison to traditional dating sites such as meetic or adopte un mec, Tinder looks modern and innovative, since it is ´mobile first` designed. The popularity of Tinder is further supported by the “app’s simplistic card-playing user-friendly interface design” (LeFebvre 1214). Indeed, Tinder interface is straightforward and presents only basic information. For instance, users can upload up to 9 photos to their profile as well as a biography of 500 words maximum. Recently, Tinder’s initial platform interface has expanded since profiles can be linked to Instagram and Spotify. Everything is made to facilitate the user experience. Not only the service itself is innovative: users are connected to others via suggestions based on their friends and common interests determined through the Facebook network. It also relies on geographic proximity as the app uses the latest location data stored in the user’s smartphone. Thus, the more the service is being used, the more the experience will improve (Bertier n.pag.). “Swap, match, talk and repeat” summarizes what Tinder expects from its users.

Addictive Game

Figure 2: Tinder Profile

On top of its inventive interface, Tinder has an addictive aspect. The interface of the application contributes to its success, with a design that encourages interaction with the ergonomics of the ‘swipe’. It is providing a fun user experience for a new form of casual flirting, which can be addictive (Bertier n.pag.). The application plays on a psychological technique originally developed around gambling, also known as the ‘variable rewards’, where rewards increase as the user spends more time on the platform. On Tinder, this means that users will tend to swipe continuously to maximize their chances of hitting the jackpot (Bertier n.pag.). The action of ‘Tindering’ then becomes as important as the potential date itself (Chamorror-Premuzic n.pag.). The fear of missing out on this coveted ‘prize’, added to the playful side of the application, then encourages users to return to the app regularly, thus guaranteeing long-term success. “It’s not uncool to scroll through Tinder with friends, and your non-single friends are all dying to ‘play’ for you”, wrote Issie Lapowsky in Wired. The term ‘play’ really shows how much Tinder can look like a game. “A lot of the gratification itself is from just using the app and playing with it” (James qtd. in Matsakis). The success of Tinder’s interface has been proven by the fact that many other apps, such as SomHome, Pitcher, Jobr or Flic, copied the swipe navigation and its playful approach. Other elements also make Tinder special: users do not need to create an extensive profile as they would on dating sites, the large number of profiles visible in a short amount of time, the low risk of frontal rejection since two people can only come into contact in the case of mutual approval, the balanced presence of men and women on the service or the possibility of cutting off a conversation by deleting a match.

Even though the creator of Tinder tends to say that the application is made to find true love (Ballet n.pag.), its interface encourages playing the game to get more matches. The interface produces a discourse where interactions can be interpreted as casual, one-time-only, rather than putting in the effort and building a sustainable, meaningful relationship.

Facebook Dating: Not Just Hook Ups

Figure 3: Swiping

Facebook wanted to enter the dating scene with its own feature. However, as Zuckerberg claimed in his keynote speech, it would differ from other dating apps out there. “This is going to be for building real long-term relationships, not just hook ups” (F8 2018 Day 1 Keynote). It could be seen as an indirect sneer at Tinder, as popular media have written extensively about it being a hook up app. For example, an article on vanityfair.com sparked a tweetstorm on the one-night-stand culture Tinder would have helped to establish (Brogan n.pag.). Facebook thus has a different ‘vision’ (Light et al. 9) for what dating should be. How the company itself frames the function of its upcoming feature is an important factor in how it will be designed. This project will therefore briefly touch upon the discourse the company has created on Dating.

Meaningful Relationships

Facebook Dating’s product manager Nathan Sharp says they “wanted to make a product that encouraged people to remember that there are people behind the profiles and the cards that they’re seeing. We wanted a system that emphasizes consideration over impulse. We want you to consider more than that person’s profile photo” (Constine n.pag.). By not just swiping right the second you see someone’s profile picture, but instead spending the time to get to know the person behind it, Facebook wants to create meaningful relationships that start online on its platform.

Chris Cox adds to Sharp´s argument that Facebook Dating will be more about personalities rather than appearances. “We like this [groups and events] by the way because it mirrors the way people actually date, which is usually at events and institutions they are connected through” (F8 2018 Day 1 Keynote).

As Facebook is mimicking how people meet offline, it is ‘capturing’ that activity (Agre 744) – transferring and reconfiguring it digitally and thus “materializing new forms of sociality” (Ruppert et al. 3). This may then alter the meaning of that activity (Agre 746). This project aims to investigate how such a rendering of offline dating takes shape on Facebook, by taking into account multiple human and nonhuman actors that together create its meaning online (Bucher 481). To see how the idea behind the feature has made it into the design, and how this differs from the discourse constituted by Tinder’s interface, this project now continues with a discursive interface analysis of Facebook Dating.

How Does Facebook Dating Work?

Figure 4: Icebreakers

Instead of displaying all users that are close-by, such as Tinder and Grindr, Facebook Dating will only list people who have similar interests as you have. This includes places, events, and Facebook friends. This decreases the number of random encounters and increases the likelihood of meaningful ones according to Facebook (F8 2018 Day 1 Keynote). Users can choose what they show about themselves on the platform, giving the users more control over how they portray themselves to potential partners. By suggesting people based on their likes, they hope to design a platform that is geared toward creating lasting relationships instead of hook ups and one-night-stands.

Facebook has implemented multiple features to encourage lasting relationships. Facebook Dating departs from the swiping interface that is seen on Tinder and other popular dating apps and presents profiles in a list instead. This shift away from Tinder’s game-like interface establishes Dating as the platform for serious relationships. The interface encourages users to deliberate on the profile they see before deciding whether they are interested or not. They can then click on a part of the profile, for instance, a photo or one of the places a user has been, and use that as an icebreaker. This differs from Tinder because it offers a rich profile that users can ponder upon and determine compatibility with the other user.

It is important to Facebook that Dating becomes a safe environment, as Tinder has been plagued by bots in the past (Nazer et al. n.pag.). First of all, Facebook has a strict policy regarding fake profiles. If a profile does not seem genuine, it will be banned until the user can confirm their identity. Secondly, Facebook does not allow users to send multiple messages before the other user has responded. This restriction has been made to prevent users from being harassed by receiving an endless stream of messages. The Dating platform is also completely unpopulated by links and pictures, in order to prevent users from receiving unsolicited material.

Limited Self-Expression

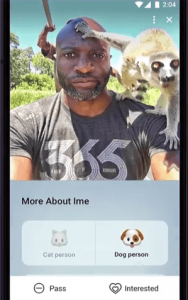

Figure 5: Lemur

Facebook presents Dating as a way for people to find lasting relationships. Facebook can find new connections for its users by having them answer 20 questions about themselves. What is contradictory about these questions, is that people are not free to answer how they see fit, but instead have to choose between two or more set options. For example, users are asked to answer if they are a dog or a cat person. Firstly, this creates a false dichotomy; suggesting that enjoying the company of cats or dogs is mutually exclusive. Secondly, this severely limits the expression of people who do not fall into the categories set by the false dichotomy. What about people who love lemurs? This may seem like a silly question, but when a platform aims to create lasting, meaningful relations, it may become an issue.

(No) Time For Love

Facebook executives already contended that the new feature will be more about quality than quantity. Unlike Tinder, Facebook Dating focuses more on who the person is rather than how one looks (Wills n.pag.). Facebook gives users the option to express themselves, to attract more potential life-partners and to get to know other users better before choosing to engage with them. Tinder users are discouraged to write long biographies on their profiles. In addition, it seems that on Tinder there is a higher probability of having random encounters as the matching process is not based on similarities other than location and Facebook friends. Facebook Dating wants to offer its users a safer place where the risk of being ‘spammed’ is lower. Where Tinder is often described as a platform for hook ups, Facebook Dating aims to form lasting, meaningful relations between its users.

Tinder focuses on playing the game. Swiping and matching is not meant to create relationships. After all, winning the game, thus finding love, means Tinder loses two users at once. By integrating Dating into the greater Facebook platform, the outcome of using the app is not diminishing its user base. Facebook ensures its longevity, as users are still generating and sharing data, though in a different stage of their lives, on a different part of the platform. Facebook stays with the happy couple throughout their lives, building a long-term relationship with its users itself.

Figures

Figure 1: Usage of Dating Sites and Apps. Source: Pew Research Center

Figure 2: Tinder Profile. Source: Tinder App

Figure 3: Swiping. Source: Don´t Believe the Hype

Figure 4: Icebreakers. Source: F8 2018 Day 1 Keynote

Figure 5: Lemur: Source: F8 2018 Day 1 Keynote

Bibliography

Agre, Philip. “Surveillance and Capture: Two Models for Privacy.” Information Society 10.2 (1994): 101–127.

Ashwini, Amit. “What Are The Various Phases Of Mobile App Development?” Medium. 2017. The Startup. 14 October 2018. <https://medium.com/swlh/what-are-the-various-phases-of-mobile-app-development-4f0a1748e619>.

Ballet, Virginie. “Accusé de tuer la romance au profit des coups d’un soir, Tinder se fâche tout rouge.” Next.libération.fr. 2015. Libération. 17 October 2018. <https://next.liberation.fr/sexe/2015/08/12/accuse-de-tuer-la-romance-au-profit-des-coups-d-un-soir-tinder-se-fache-tout-rouge_1362383>.

Bertier, Anne-Sophie. “Comment Tinder a construit sa croissance explosive?” Don’t Believe The Hype. 2015. Don’t Believe The Hype. 15 October 2018. <http://www.dontbelievethehype.fr/2015/08/comment-tinder-construit-sa-croissance-explosive-application/>.

Bratton, Benjamin. “Platform and Stack, Model and Machine.” The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2015. 41-72.

Brogan, Jacob. “Swipe Left.” Slate. 2015. The Slate Group. 17 October 2018. <http://www.slate.com/articles/technology/future_tense/2015/08/tinder_s_tweetstorm_over_nancy_jo_sales_vanity_fair_dating_apocalypse_article.html?via=gdpr-consent>.

Bucher, Taina. “The Friendship Assemblage: Investigating Programmed Sociality on Facebook.” Television & New Media 14.6 (2013): 479-493.

Bucher, Taina, and Anne Helmond. “The Affordances of Social Media Platforms.” The Sage Handbook of Social Media. Eds. Jean Burgess, Alice Marwick and Thomas Poell. London: Sage Publications, 2017. 233–253.

Carman, Ashley, and Casey Newton. “Facebook Dating Launches Today with a Test in Colombia.” The Verge. 2018. Vox Media. 8 October 2018. <https://www.theverge.com/2018/9/20/17871690/facebook-dating-release-colombia-test>.

Chamorro-Premuzic, Tomas. “The Tinder Effect: Psychology of Dating in the Technosexual Era.” The Guardian. 2014. Guardian News. 18 October 2018. <https://www.theguardian.com/media-network/media-network-blog/2014/jan/17/tinder-dating-psychology-technosexual>.

Constine, Josh. “Inside Facebook Dating, Launching First in Colombia.” TechCrunch. 2018. Oath Tech Network. 8 October 2018. <https://techcrunch.com/2018/09/20/how-facebook-dating-works/>.

Davis, Jenny, and James Chouinard. “Theorizing Affordances: From Request to Refuse.” Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society 36.4 (2016): 241–248.

“F8 2018 Day 1 Keynote.” Facebook for Developers. 1 May 2018. 13 October 2018. <https://developers.facebook.com/videos/f8-2018/f8-2018-day-1-keynote/>.

Lapowsky, Issie. “Tinder May Not Be Worth $5B, But It’s Way More Valuable Than You Think.” Wired. 2014. Condé Nast. 18 October 2018. <https://www.wired.com/2014/04/tinder-valuation/>.

LeFebvre, Leah. “Swiping Me off My Feet: Explicating Relationship Initiation on Tinder.” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 35.9 (2018): 1205–1229.

Light, Ben, Jean Burgess, and Stefanie Duguay. “The Walkthrough Method: An Approach to the Study of Apps.” New Media & Society 20.3 (2018): 881–900.

Marres, Noortje. “The Redistribution of Methods: On Intervention in Digital Social Research, Broadly Conceived.” The Sociological Review 60.S1 (2012): 139–165.

Martin, Alan. “Colombia Is Getting to Test Facebook’s Dating Experiment.” The Inquirer. 2018. Incisive Business Media. 8 October 2018. <https://www.theinquirer.net/inquirer/news/3063184/colombia-is-getting-to-test-facebooks-dating-experiment>.

Matsakis, Louise. “Facebook Dating Is Rolling Out. Here’s How It Differs From Tinder.” Wired. 2018. Condé Nast. 18 October 2018. <https://www.wired.com/story/facebook-dating-how-it-works/>.

Nazer, Tahora et al. “A Close Look at Tinder Bots.” 2017. n. pag.

Numera.com. “Tinder : Historique, Présentation, Chiffres-Clés.” Numerama. N.d.. 15 October 2018. <https://www.numerama.com/startup/tinder>.

Ruppert, Evelyn, John Law, and Mike Savage. “Reassembling Social Science Methods: The Challenge of Digital Devices.” Theory, Culture & Society 30.4 (2013): 22–46.

Sengupta, Devina, and Anumeha Chaturvedi. “Is Our Data Safe There? Clients Ask App Makers.” The Economic Times. 2018. Bennett, Coleman & Co.. 8 October 2018. <https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/tech/internet/is-our-data-safe-there-clients-ask-app-makers/articleshow/63651167.cms>.

Smith, Aaron, and Monica Anderson. “5 Facts About Online Dating.” Pew Research Center. 2016. Pew Research Center. 13 October 2018. <http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/02/29/5-facts-about-online-dating/>.

Stanfill, Mel. “The Interface as Discourse: The Production of Norms Through Web Design.” New Media & Society 17.7 (2015): 1059–1074.

Toma, Catalina. “Developing Online Deception Literacy While Looking for Love.” Media, Culture & Society 39.3 (2017): 423–428.

Van Dijck, José. “Search Engines and the Production of Academic Knowledge.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 13.6 (2010): 574–592.

Wills, Todd. “Social Media Giant Tests the Waters with Facebook Dating in Colombia.” The Bogotá Post. 2018. The Bogotá Post. 18 October 2018. <https://thebogotapost.com/2018/09/26/facebook-dating-launches-colombia/>.

Wolverton, Troy. “Facebook is Taking on Tinder with the Official Launch of Its Dating Service — But It’s Only in Colombia For Now.” Business Insider. 2018. Business Insider Nederland. 8 October 2018. <https://www.businessinsider.nl/facebook-launches-facebook-dating-in-colombia-2018-9/>.