Facebook Gaming: Live Streaming the Perils of Data Privacy

The ability to record and live stream video games has completely reformed the gaming industry as it became the birthplace of popular online live streaming communities. Why do younger people today spend more time watching gaming content than playing video games? The rise of gaming content not only created new opportunities for gamers to share their interests and gameplay to a large network of gamers, but also social network platforms to take part in the tug of war for users and most importantly data.

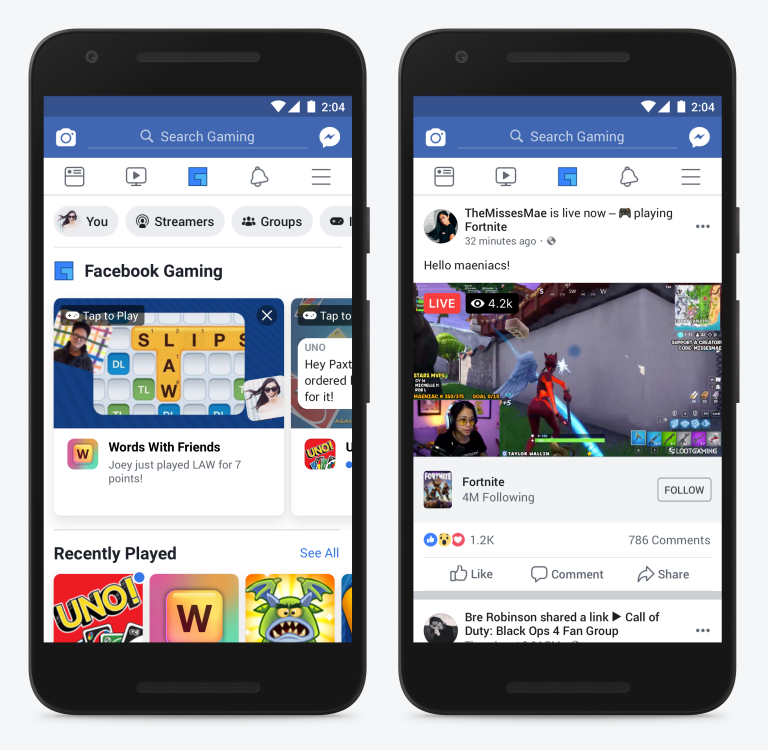

Recently, Facebook decided to take a slice of Twitch’s pie launching its own “gaming” tab located in the main navigation of the Facebook application. Facebook’s new “gaming” tab is separated into three categories of gaming content including instant games (simple HTML5 games), gaming videos (includes recorded and live content of streamers and E-Sports channels), and gaming groups (Dellinger). Facebook will only display the gaming shortcut tab through an algorithm that determines which users are regularly engaged in gaming-related activities (Price). Other users may access the feature through the hamburger button (≡).

“Identity” on a Social Network

Facebook’s approach to gaming is unique, because like no other platform it integrates the user’s established social media profile into the public gaming community creating discourse about data and privacy. On other platforms viewers remain semi-anonymous, concerning concepts of “online identity” and how someone acts or behaves on online platforms. A typical gamer casually redefines their identity on online communities/platforms in a form of an avatar or through usernames that represent their online identity (Costa Pinto, Reale and Segabinazzi). Facebook breaks these rules and encourages the user to log in with their personal Facebook account to connect with a larger network of friends. However, some users might consider using fake Facebook accounts to stay semi-anonymous, although it goes against Facebook’s policy.

Facebook as a well-established social network of 2.41 billion monthly active users (as of June 30, 2019) aims to reward streamers with their very own monetization program, while luring in younger audiences to be victims of Facebook’s advertisements. Although, Facebook is not a common platform for gamers to watch and host live streams, the number of active users and connected network of friends makes it much easier for streamers to standout and gain viewers compared to other platforms like YouTube and Twitch (Tracy).

Counting Stars for a Living

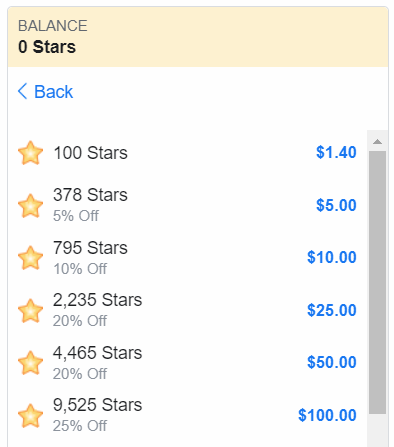

Along with the ease of access to gaming content, Facebook also included a Level Up Program designed to award gamers with incentives for livestreaming content on the platform. To be eligible for the program, the streamer needs to have at least 100 followers on their personal “Gaming Video Creator” page and streamed at least four hours within at least two days in the past two weeks. Once partnered, the streamer will have access to “Facebook Stars”, which is a feature for viewers to financially support a streamer by purchasing stars. Viewers can directly send stars to their favorite streamer bundled with a message, which displays to both the streamer and other viewers. For each star, Facebook pays the streamer roughly $0.01 USD. To attract more streamers to the platform, Facebook only takes a maximum share of 30% and minimum of 5% depending on how many stars the viewers purchase, which is more profiting compared to Twitch that roughly takes 50% of the cut (Perez). With more competition among streaming platforms, it always benefits streamers and ultimately viewers, while platforms are forced to innovate to maintain viewership.

Who will become Facebook Gaming’s rising Star?

An emerging trend not only among streaming platforms, but also social platforms are famous “influencers”, endorsers who have persuasive powers to shape audience attitudes and the direction of a platform (Freberg, Graham and McGaughey). Facebook gaming currently lacks famous gaming “personalities” (influencers) who already have a mass follower base, to build awareness and familiarity of Facebook’s own streaming platform (Aaker). One perfect example is Tyler “Ninja” Blevins, who recently moved to “Mixer”, Microsoft’s own streaming platform from Twitch. The exclusive deal was worth around $10-50 million and within the first week of the announcement Ninja gained more than 1.5 million subscribers on Mixer (Gravelle). The move did drive traffic and raised awareness to Mixer’s platform, but the question is how many users took time to browse through other streamers on the platform? Facebook took another approach and partnered up with major E-Sports organizations like ESL One to exclusively broadcast E-Sports games on the platform, temporally drawing in large crowds of E-Sports fanatics to the platform (Statt).

Facebook as a Data Mining Infrastructure

Why is Facebook interested in gaming content, when they are the largest social media platform? Facebook is more than just a platform, but an infrastructure integrated with ecosystems of connective media (van Dijck). Through an evolutionary perspective, Facebook’s programmable architecture allowed it to gain infrastructural properties, through integrations and the processes of “platformisation and infrastructuralisation” that promoted Facebook’s technological expansion (Helmond). As an infrastructure, Facebook has the ability and technology to convert raw data of users engaged with gaming content into means of control and surveillance.

Although developments in technology allowed gamers and streamers to engage in new types of content in the form of collaborative play, it does come with a cost. Gamers might be giving up their identity in the form of data both inside and outside of games. To fully experience Facebook’s gaming platform, it forces users to login, which in some sense invades privacy. This opens new segments in Facebook’s pool of data among younger audiences who become victims of corporations that take data to mediate and direct actions (Walker). The complex nature of Facebook’s algorithms allows it to combine new data with existing data gathered from established Facebook profiles to predict user patterns and behaviors. Users now become the resource for data collection as Facebook consumes user identities based on the ethics of “dataveillance” (Gitelman 10).

Facebook’s involvement in the gaming industry, therefore, makes it a new actor within the landscape of gaming that could affect the direction of users and gaming content. The affordances of Facebook gaming do not only build on social benefits of building gaming communities, but also benefits Facebook in terms of profitability and the race for user data. Facebook has become more of a monopolized infrastructure as it mines for user data from various segments in emerging forms of new media.

Works Cited

Aaker, David Allen. Managing Brand Equity : Capitalizing on the Value of a Brand Name. New York: Free Press, 1991. Print.

Costa Pinto, Diego, et al. “Online identity construction: How gamers redefine their identity in experiential communities.” Journal of Consumer Behaviour 14.6 (2015): 399-409. Web. <https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1556>.

Dellinger, AJ. Facebook’s redesigned app gets a dedicated gaming hub. 14 March 2019. Web. 9 September 2019. <https://www.engadget.com/2019/03/14/facebook-gaming-dedicated-tab/>.

Facebook Company Info. n.d. Web. 13 September 2019. <https://newsroom.fb.com/company-info/>.

Facebook Level Up Program. n.d. Web. 13 September 2019. <https://www.facebook.com/fbgaminghome/creators/levelup>.

Freberg, Karen, et al. “Who are the social media influencers? A study of public perceptions of personality.” Public Relations Review 37.1 (2011): 90-92. Web. 13 September 2019. <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2010.11.001>.

Gitelman, Lisa. “Raw Data” Is an Oxymoron. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2013. Print.

Gravelle, Cody. Microsoft Has Paid For Over 1.5 Million Subscriptions to Ninja’s Mixer. 21 August 2019. Web. 13 September 2019. <https://screenrant.com/ninja-mixer-subscriptions-1-5-million/>.

Helmond, Anne. “Facebook’s evolution: development of a platform-as-infrastructure.” Internet Histories 3.2 (2019): 123-146. Print.

Perez, Sarah. In a challenge to Twitch and YouTube, Facebook adds ‘Gaming’ to its main navigation. 14 March 2019. Web. 13 September 2019. <https://techcrunch.com/2019/03/14/in-a-challenge-to-twitch-and-youtube-facebook-adds-gaming-to-its-main-navigation/>.

Price, Rob. Facebook is launching a new gaming hub and app to try and lure gamers to the social network. 14 March 2019. Web. 13 September 2019. <https://www.businessinsider.nl/facebook-announces-new-gaming-tab-streaming-groups-casual-2019-3?international=true&r=US>.

Statt, Nick. Fb.gg is Facebook’s game streaming hub for stealing Fortnite streamers away from Twitch. 7 July 2018. Web. 13 September 2019. <https://www.theverge.com/2018/6/7/17439928/facebook-game-streaming-hub-fortnite-streamers-twitch-youtube>.

Tracy, Phillip. Facebook makes a rival out of Twitch with fb.gg streaming platform. 8 June 2018. Web. 9 September 2019. <https://www.dailydot.com/debug/facebook-fbgg-game-stream-fornite/>.

van Dijck, José. The culture of connectivity: A critical history of social media. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013. Print.

Walker, Austin. “Watching Us Play: Postures and Platforms of Live Streaming.” Surveillance and Society 12.3 (2014): 437-442. Web. <https://doi.org/10.24908/ss.v12i3.5303>.