A Rhetoric of WeWalk-ing. Smart Canes and “feeling of freedom” in the urban environment

The new uses of smart technology are being constantly introduced, and unlike a cat selfie device or a cute planter that aim to add some fun to our humdrum existence, WeWALK smart cane attempt to make a difference. This new electronic walking stick for visually impaired people aims to alter the way they navigate and interact with the city.

According to the World Health Organization, there is over 250 million visually impaired people globally, among which about 50 million use a cane. This is the target group of the WeWALK smart cane, created by Kürşat Ceylan, an engineer, the CEO and co-founder of Young Guru Academy (YGA), the non-profit that helped to create the device.

Cane vs full participation

Visually impaired people face everyday difficulties in independent mobility. However, the use of the “traditional” cane as a mobility aid detecting obstacles has two major limitations. Firstly, it can only spot obstacles up to the knee-level. Secondly, the cane can only inform about obstacles within one metre from the user. Also, moving vehicles cannot be detected until getting dangerously close to the person (Meinhardt and Engel). While Ceylan, being blind himself, is perfectly familiar with the need for “full participation”, from which many visually impaired people are being held back, he knew that he had found his niche. “In these days we are talking about flying cars, but these people have been using just a plain stick” ( Scott-Clarke and Lewis).

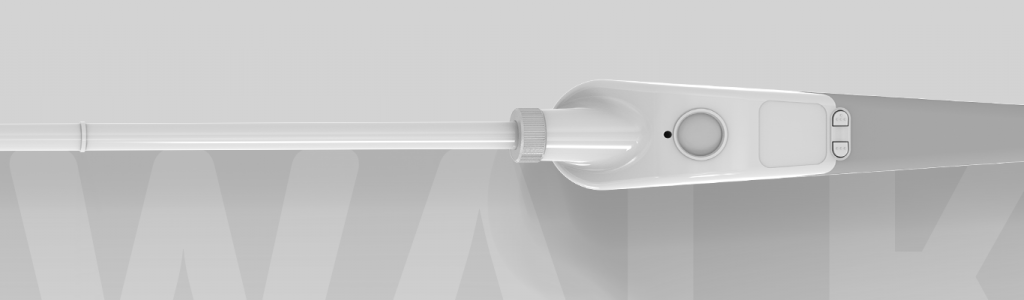

WeWALK combines both a style of a traditionally looking cane, completed by a handle with a touchpad and the user-centred design. It has built-in speakers and Voice Assistant that cooperates with Google Maps. It is also compatible with a smart phone via Bluetooth. The special sensors alert the user with vibrations when an obstacle appears both at the ground and above the chest level within 160 cm. WeWALK also features an LED light to help partially sighted people. While Google Maps offers navigation system when walking, it is also possible to integrate apps such as Uber Lyft to access urban mobility. As the company gains interest, Ceylan hopes to add more innovations in the future, including partnership with ride-share apps and other transportation services. Each new integration would bring new developments and new features, requiring a regular software updates (Panda; Richman-Abdou; WeWALK). Therefore, with the constant grow of the WeWALK, it will become more and more a market “platform”, although there is no information about possible fees of the new applications.

However, due to the growing interest in the sector, WeWALK faces competition with other products such as Smart Cane Device, BAWA cane or SmartCane. SmartCane, for example, presents itself as a simple, “affordable” device, easy to learn and use. And it is the use and the practice the creators put the greatest emphasis on. In order to become an expert user, a person needs to undergo a short training to learn the correct ways of using the device in real-life scenarios (SmartCane). While WeWALK focuses on the traits of the cane that are supposed to solve the problems and add more to it through smartphone integration (WeWALK).

To understand both walking and WeWALK-ing

Thus, WeWALK aims at making the urban environment more friendly and accessible with the support of technology. The smart cane is therefore important to integrate the visually impaired people into the urban life and mobility as experiences of mobility-challenged pedestrians (MCPs) should not only be considered in terms of simply the limitations of those people, but also: principles of pedestrian experience, pedestrian environment and pedestrian characteristics (Jeong et al.).

Yet, when it comes to MCPs, the “traditional” approach to mobility, creation of space and interaction with the urban environment does not necessarily apply. Ontogenetic conceptions of space and awareness of the role of representation and meaning show that urban design is much more than a context for social action. It is both relation and political (Brenner et al.). For instance, de Certeau argues that those whose voyeuristic perspective conforms to the general “concept city” (95) (eg. architects, urban planners, politicians, etc.) are guilty of “misunderstanding of practices” (93).They cannot fully comprehend reality of street life below from the vantage point of the (mobile) pedestrian. De Certeau ‘s “rhetoric of walking” explores the overlap between walking and composing. Hence, it introduces walking (and interaction with the city) as both an object of study and a method of investigation (Brenner et al.). However, the users of WeWALK are not “regular” pedestrians. They do not interact with, for example, the “capitalist” layer of the city as these dimensions are mostly fixed by semiotic (hence usually “visual”) information. The visually impaired people also do not interact with the city like de Certeau’s “walker”, and probably will not do it when using the WeWALK that provides them with a fixed route prepared by Google Maps.

Feeling of freedom for everyone?

“No one should be deprived of feeling of freedom,” says Kürşat Ceylan. And his WeWALK, advertised as “The World’s Most Innovative Smart Cane”, aims at giving new opportunities to visually impaired people, to walk more confidently and to interact with the urban environment in the new ways that were out of reach to them before. The device itself also opens new areas of analysis for scholars as the “traditional” theories have not particularly considered the MCPs, and especially not those using smart technology to interact with the urban environment.

Nevertheless, almost 90% of the blind people live in the developing countries, with majority below the poverty line. Over half of them is unemployed because of the limited number of jobs they can do (Branig and Engel). Hence, their mobility restrains them from interacting with people and social activities. However, this “feeling of freedom” is still far away from the vast majority of the WeWALK target group when costing almost $500.

References:

Branig, Meinhardt, and Christin Engel. “SmartCane: an active cane to support blind people through virtual mobility training.” Proceedings of the 12th ACM International Conference on PErvasive Technologies Related to Assistive Environments. ACM, 2019, https://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=3322742 (Accessed 21 September 2019).

Brenner, Neil, Peter Marcuse, and Margit Mayer. “Cities for people, not for profit.” City 13.2-3 (2009): 176-184.

Certeau, Michel de. The Practice of Everyday Life. University of California Press, 1984.

Jeong, Dong Yeong, et al. “A pedestrian experience framework to help identify impediments to walking by mobility-challenged pedestrians.” Journal of Transport & Health 10 (2018): 334-349, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214140518300434 (Accessed 18 September 2019).

Panda, Sukanya. “WeWALK: Smart-Cane for the Blind with Mobile Integration.” DesignWanted, 25 June 2019, https://designwanted.com/tech/wewalk-smart-cane/ (Accessed 19 September 2019).

Richman-Abdou, Kelly. “Blind Engineer Invents a Smart Cane That Guides Using Google Maps and Sensors.” My Modern Met, 6 Sept. 2019, https://mymodernmet.com/wewalk-smart-cane/ (Accessed 19 September 2019).

Scott-Clarke, Edd, and Nell Lewis. “The Tech Empowering Disabled People in Cities.” CNN, Cable News Network, 31 May 2019, https://edition.cnn.com/2019/05/29/business/disability-technology-transport/index.html (Accessed 19 September 2019).

Smartcane, 2019, http://smartcane.saksham.org/overview/ (Accessed 19 September 2019).

“Vision Impairment and Blindness.” World Health Organization, World Health Organization, 11 Oct. 2018, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/blindness-and-visual-impairment (Accessed 21 September 2019).

WeWALK Smart Cane, 2019, https://wewalk.io/ (Accessed 22 September 2019).