Digital Audio Workstations—The Infrastructure of Music Production

Digital Audio Workstations, or DAWs, have become ubiquitous in the landscape of contemporary music production. The development of DAWs has not only revolutionized studio production workflows, but also put the tools to create sophisticated music and sound projects into the hands of a greatly expanded market. Modern DAWs are relatively affordable and will run on your average laptop PC. The impact of these software has been especially salient in the world of electronic music, where entire genres have been spawned in the bedrooms and living rooms of amateur producers the world over.

A Brief History of DAWs

The first attempt at creating a DAW came from Soundstream in 1975. The Soundstream Digital Editing System allowed users to work on tracks using a tape recorder and analogue to digital converter, software allowed for digital fading and splicing of the tracks.

More attempts at developing a comprehensive audio workstation followed in the next decade. The continuous gains in processing power and greater uptake of personal computers in the 1980s allowed for more complex functions and made DAWs more accessible.

A massive boost for the DAW movement came with the development of MIDI technology announced by Moog in 1982. MIDI is a technical standard and communications protocol for instruments and computers. When in 1985 Atari released the 520 ST computer which had built-in MIDI ports, the stage was set for music production to break out of the studio.

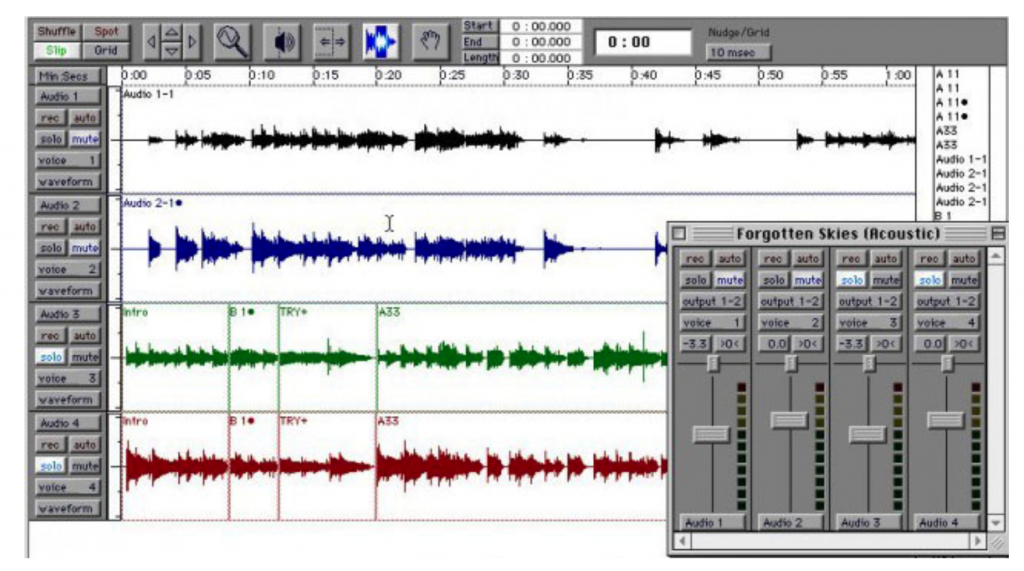

1985 also saw the release of Digidesign’s audio editing software “Sound Designer”, by 1989 this had developed into Pro Tools, the most comprehensive DAW to date. In 1994, a feature was added to Pro Tools that allowed for third party plug-ins and many companies started developing custom effects to use alongside the DAW. The ability to run additional plug-ins is one of the predominant features of DAWs today.

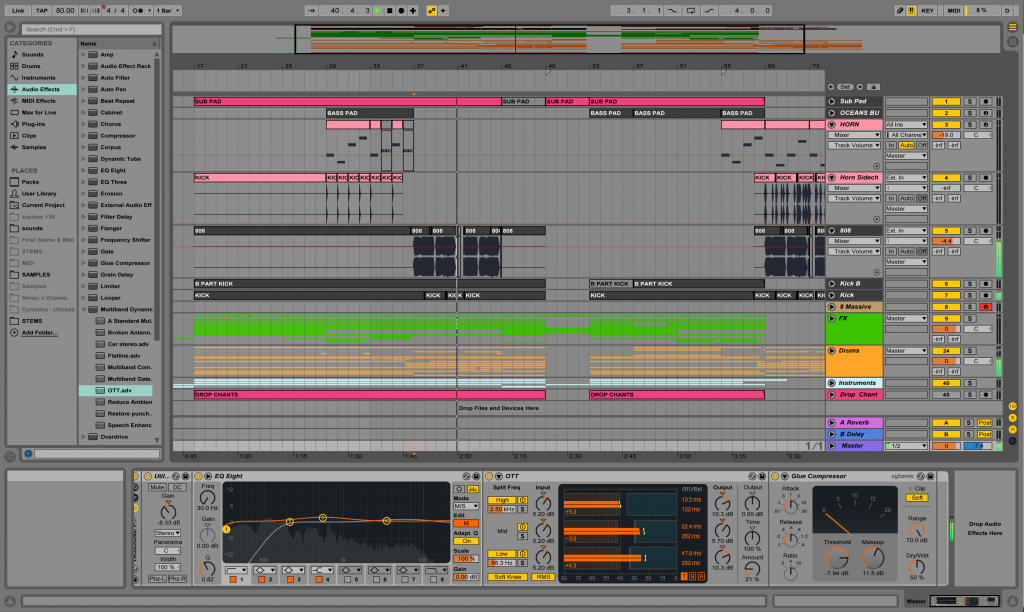

By the turn of the millennium most the main features of DAWs as we know them today were present and the number of functions continued to increase as computers grew in power. These days the requirements to run the latest version of the most popular DAW—Ableton—are easily reached by most computers. Add to this their relatively low price and possibility for illegal downloading, and we can observe that DAWs have entered the mainstream.

Research Methodology

In order to investigate the role of DAWs in current music production practices, both professional and amateur, we designed a two-pronged research model, gathering both qualitative and quantitative data.

As part of our qualitative approach we interviewed several professional music producers to establish how they used and viewed audio workstations and what they thought about their position in the contemporary music industry.

To collect quantitative data we created a questionnaire which sought to investigate and analyze people’s DAW usage and establish the relation of these software to other aspects of music production.

The full questionnaire can be seen here.

When conducting our survey, our main goal was to understand the significance and substance of Digital Audio Workstations in today’s music production landscape. Our questions were predominantly formulated to get a bigger picture of the users’ traits and background – why were they using the DAW, and in what circumstances? Did they rely solely on the interface, or were hardware instruments still important to their production process?

To disseminate our questions, we shared links to the questionnaire on several prominent music production Reddit subs and Facebook groups. We also sent the survey to the many producers we know personally in different pockets of the music industry.

The rise of social media platforms can be seen to mirror the democratizing effect of DAWs for music production—once the exclusive domain of a small and sometimes insular group of music industry professionals, to the more accessible world of music-making we see today. Online communities foster a culture of education and mutual support and have been vital to the musical growth of budding producers the world over, as we will show in the next section.

Rise of the Self-Taught Producer

One of the first things we noticed upon analysing our data was how many respondents (77.4%) learned to use their DAW through experimentation and learning by ear and even more (84.2%) classed themselves self-taught, utilizing video tutorials and free online resources.

Conversely, only 6.2% learned through formal classes or private tutoring. This illustrates just how much DAWs have impacted the way people learn music production. Before they became so widespread, formal training in audio engineering was often necessary to undertake many of the tasks that DAWs streamline.

As DAWs have become more accessible, and personal computers more powerful and widespread, the data shows many amateur producers have mastered the software through experimentation, the use of online tutorials, online support communities and self-teaching.

The large volume of self-taught DAW users might be connected to another observation drawn from the survey responses. Many DAW users are not music professionals (83%) and 40% of survey respondents have never even been in a professional music studio.

Clearly, high-end production studios and expensive equipment are not readily available to ordinary people. In the days before the popularization of home music production software, mixing a “commercially-viable song was difficult” (Peters), the technical work “required investment” (ibid) and the cost of physically producing records was out of reach for most musicians not signed to a record label.

It is not uncommon for “bedroom producers”, like Mura Masa—who started producing on DAWs at a young age— to become a major artist in the music industry. At 15, he started self-producing on Ableton, ripping samples from Youtube and other sites, then posting his tracks on Soundcloud (Stone). The young producer was soon discovered by BBC Radio 1 and later signed through his own label with the support of Interscope Records. In 2017 his debut album featured major pop-artists like A$AP Rocky and Ariana Grande and was nominated for several Grammy Awards.

Despite not having any formal music production education, using Ableton, Mura Masa has achieved massive commercial success. He is just one example of many producers who have done the same.

When 83% of respondents to our survey do not work in the professional music industry, it reinforces the notion that DAWs are giving amateurs and hobbyists the opportunity and platform for creating music. Many of these producers have even used DAWs as a springboard to break into the music business without the support of labels or industry professionals.

Computers… Plus What?

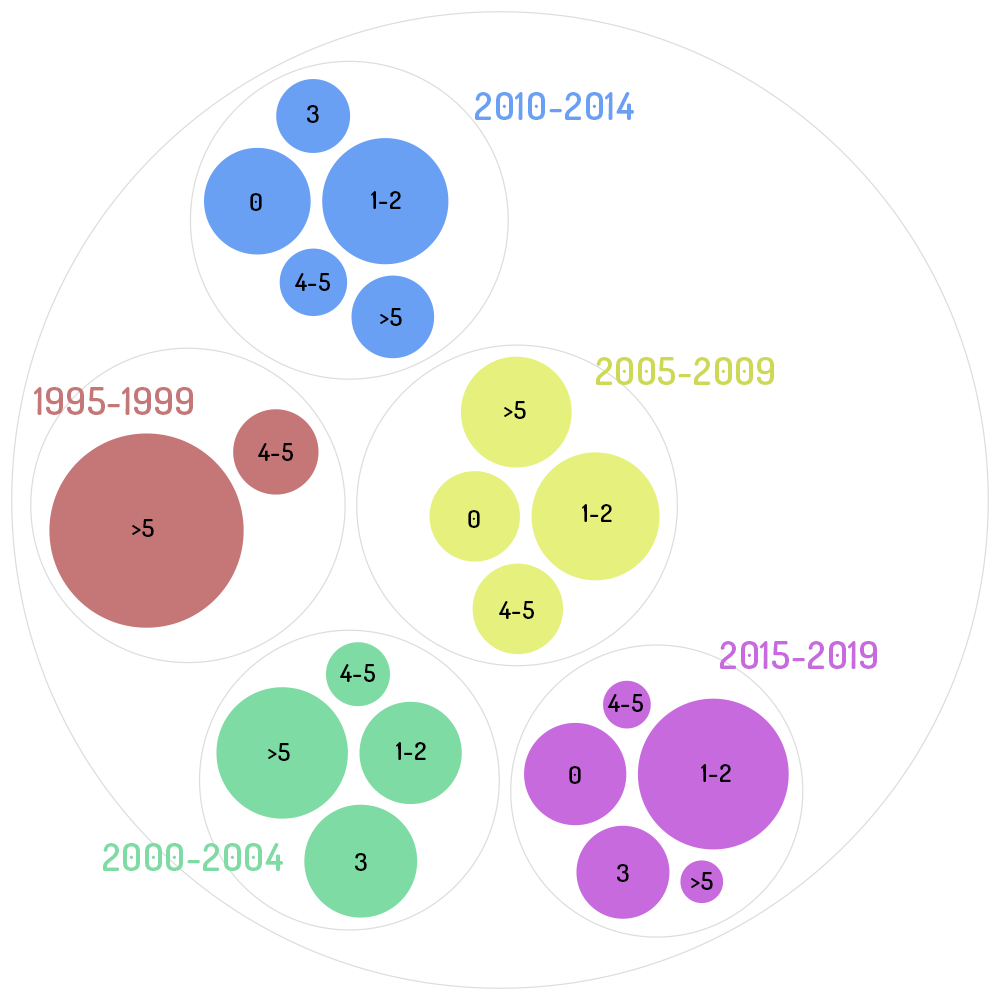

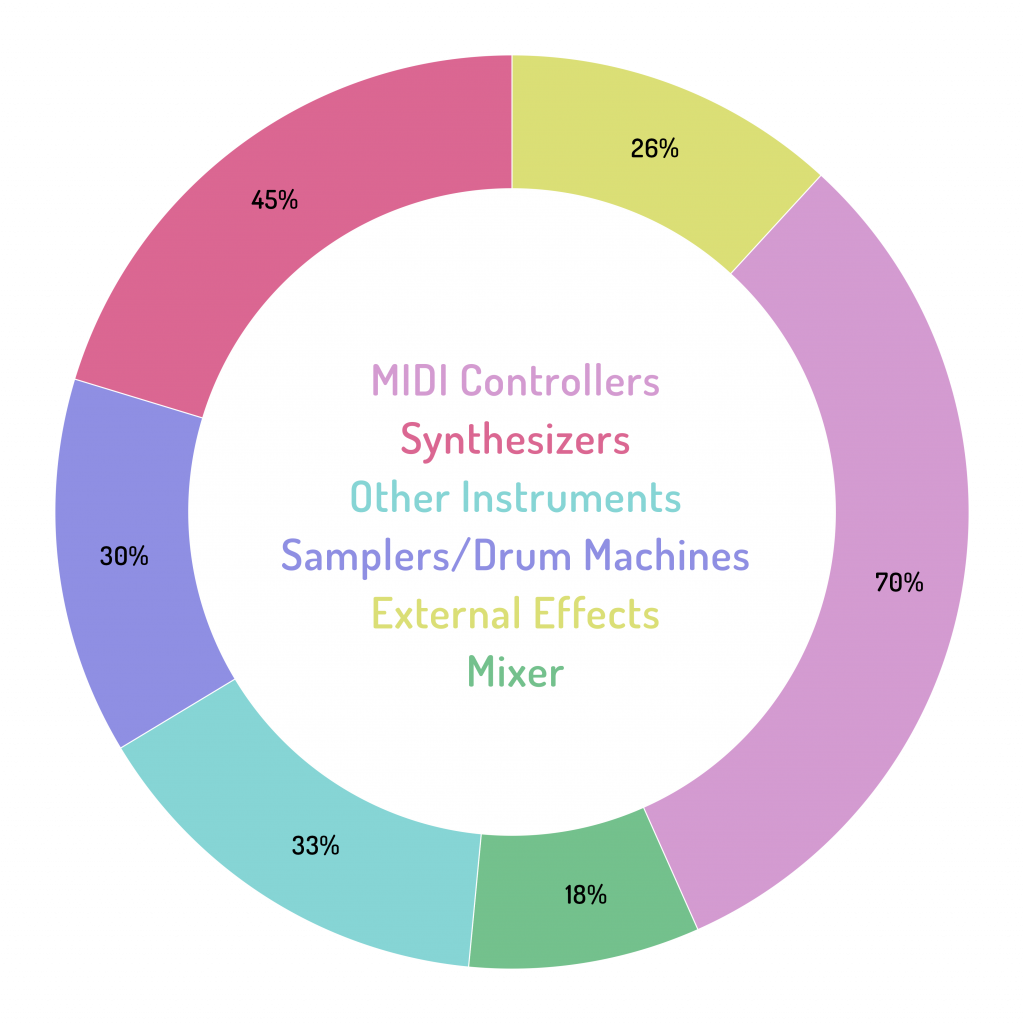

A second observation that can be drawn from our data is the dynamic role that electronic instrumentation plays in the DAW-centric music production process and the place in which these software sit within the wider suite of production tools both hard and soft. We found a direct correlation between how long survey respondents had been using DAWs and the number of different bits of equipment they used regularly in their production (Figure 4).

Considering the wealth of functionalities available on modern DAWs one might expect to find that software had all but replaced tangible instrumentation, and indeed, 65.8% of survey respondents said they never used hardware synths or drum machines in their production process.

We spoke to self-taught producer Chad Palmer (Artist name—Attic Beats) about how he first came to make music thanks to Ableton, eventually making it his full-time career: “I didn’t play an instrument growing up, so working in a DAW was really the first thing I was exposed to when it came to making my own music.”

Chad highlights that “in 2019, all you need is a computer, a DAW, and headphones or speakers” adding that “there is a virtual version of almost every instrument and synth you can think of… so unless you have the luxury of being able to purchase expensive equipment it is not necessary to do so to have a successful career.”

However, he also mentions that for him, using a DAW actually acted as a stepping-stone towards learning a new instrument, the guitar.

Chad started production using the most basic setup of a computer, a DAW, and basic MIDI keyboard—something our data suggests is widespread among many producers, especially those who have been making music for less time.

Although he started his production career thanks to Ableton, Chad stresses that starting to produce music on a computer actually led him towards a greater appreciation of what is extra to the computer interface when it comes to making music. As his career progressed, he found that he used a greater variety of instruments and plug-ins on top of Ableton. This trajectory mirrors that of many electronic musicians. It is not uncommon to start out with the most basic of music technology, creating mainly digital, sample based music. Following success, artists often graduate to become accomplished composers who orchestrate many different elements and incorporate them into their production.

Our survey data testifies to the widespread use of software plug-ins, collectively known as Virtual Studio Technologies (VSTs). As DAWs have grown more popular, the possibility of building upon their interfaces has become central to music software enhancement. In the present day, VST plugins have emerged as an essential component of the virtual audio workstation.

A plugin is “a type of software that works inside another piece of software” (Laukkonen, 1), and usually takes shape as an instrument or effect plugin. Popular VSTs like Xfer Serum, Native Instruments Massive, or Lennardigital Sylenth vastly enhance the production experience, bringing outside instruments and effects into conveniently packaged software that can be applied on most DAWs.

These plugins were “developed to replace, or compliment, physical” (1) hardware that was not only very expensive, but also took up a lot of space due to the size of hardware instruments, effects, and compression systems.

VSTs revolutionized the virtual studio and strengthened the position of DAWs within the new, more participatory music production industry. As software which is built on the platform of DAWs, the two work hand-in-hand, giving the users more autonomy and creativity without needing extra hardware or equipment.

The open source configuration of VSTs even enable producers to build their own plugins. Sausage Fattener, a two-knob compression and distortion plugin, was built by the producer duo Dada Life and has become one of the most widely used plugins in recent years. The ability for producers to enhance their own virtual studios is driving the bottom-up transformation of the music industry and leading to all kinds of user-generated innovations.

A final point here should be that many participants in our research played instruments that they did not use frequently in their music production, most often some form of strings. From this we might deduce that many of the survey respondents produce more consciously electronic music, that relies on synthesizers and quantized percussion.

We could ask “Shall art orient itself toward the digital? Or shall art merely live inside the digital, while concerning itself with other topics entirely?” (Galloway, 1). For recorded music in the 21st century, there is no option but to to reside in a digital world, at least if the artists wants to reach any sizable 21st century audience. Today, DAW technology saturates this world so that even genre’s far-detached from any explicit digital aesthetic will most likely encounter a virtual workstation at some point.

The Infrastructuralization of Audio Production Platforms

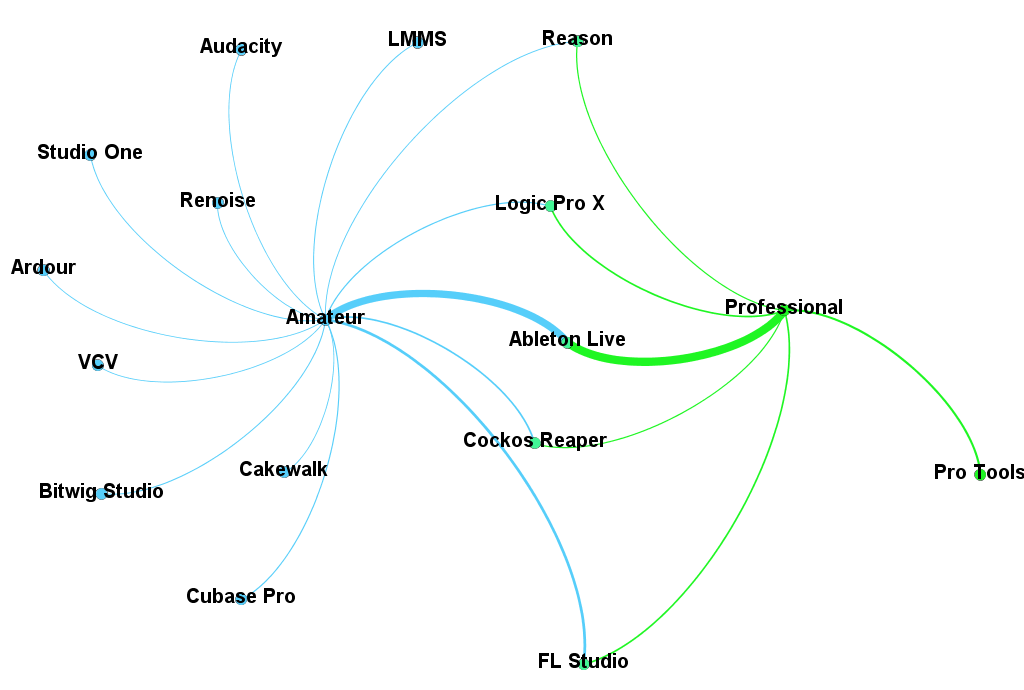

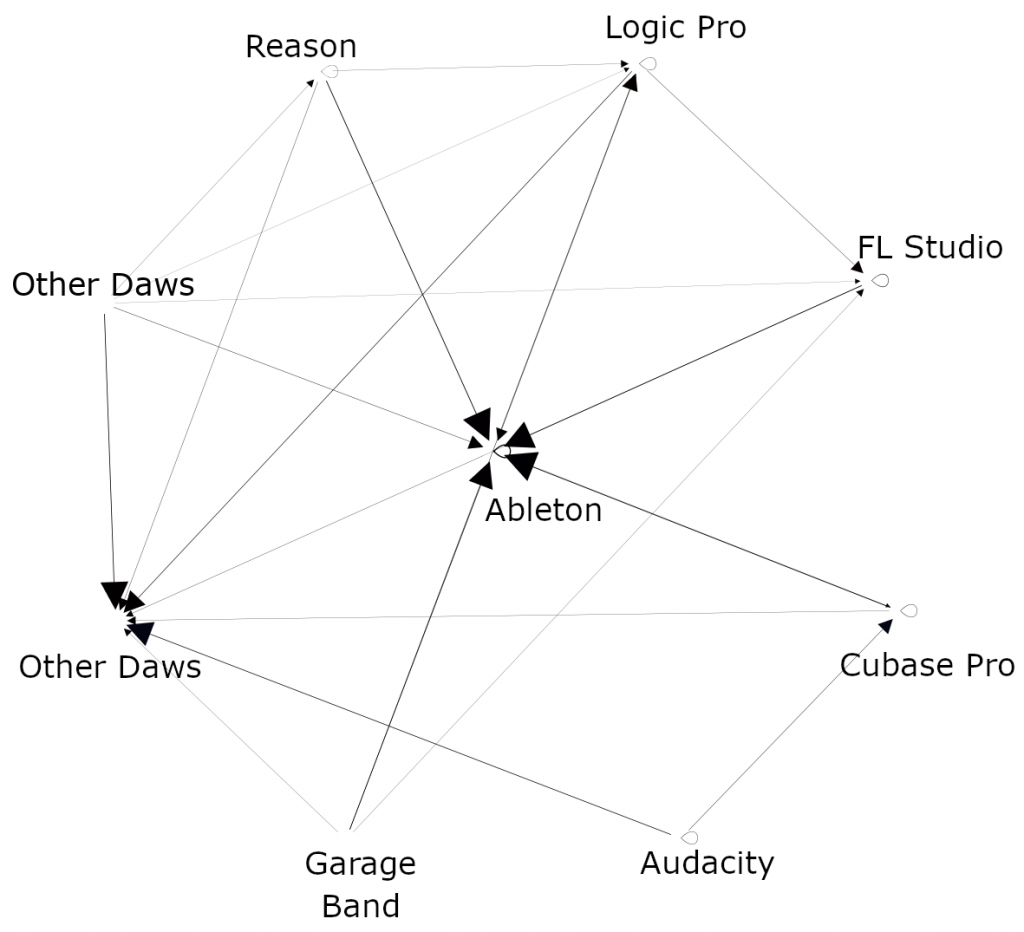

The results of our survey show that respondents overwhelmingly prefer Ableton to other DAWs and use it a lot more. This finding is backed up by other surveys, for example this one of over 30,000 respondents by ask.audio. As we can see, however, when the survey is scaled up, Ableton loses its clear lead with Logic Pro hot on its heels in second place.

We also found that music industry professionals use a smaller range of workstations than amateur or hobby producers (Figure 7). And that there were certain trends in DAW migration that can be seen in Figure 8. This demonstrates that although there are many DAWs around, industry standard has congregated around just a small number of these.

Given the ubiquity of DAW software and even the emergence of a single DAW as the market leader that our research suggests, might it be useful to think of DAWs as a kind of infrastructure? From personal experience we can attest to the appeal of a single standard for music production. As the industry moves towards ever greater standardization of file-formats and the greater inter-usability of different software, the potential for collaboration is only enhanced.

A long tradition of infrastructure studies has analysed the structures that undergird the social, cultural and economic functioning of society, from railway networks to the wires and cables through which the majority of the world’s dataflows pass today. Sociologists remind us that the term can also extend to organization operations such as the establishment of standards, conventions, classification systems and technical protocols (Star and Bowker).

DAW’s share many of the properties of infrastructures as defined by this tradition. They have become pervasive and even somewhat disappeared into the background of music production—most listeners rarely think about the kinds of software used in the making of a song; if all DAWs stopped working tomorrow, it would throw a significant spanner in the works of the global music-making machine.

Another term that has become especially popular with new media scholars is “platform”. Platforms can be understood as modular systems that allow for dynamic use by a variety of actors. DAWs are often marketed as platforms for music production given their operability with third party plugins and the MIDI protocol.

Plantin et al have highlighted the similarities between the platform concept and the more traditional idea of infrastructure. We propose to think about the growing ubiquity of DAWs in terms of infrastructuralization, a term Plantin et al employ to suggest the ways that platforms begin to look more and more like infrastructures as it becomes harder to imagine life in 2019 without them.

The infrastructuralization of DAWs has meant that currently it is extremely rare to produce music without them.

We spoke to Luigi Monteanni, an artist who co-founded the Milanese label Artetetra with Matteo Pennesi, the other half of production duo Babau. Babau approach music in a dynamic manner, mobilizing different recording techniques, analogue and digital instruments, and a range of software.

In many ways Babau and other artists signed to Artetetra explicitly reject the hegemony of DAWs. Luigi states that “the design of Ableton makes you obsess over controlling parameters and re-listening to your composition, forgetting about the expression of the track as a whole”. Where possible, he avoids DAWs and prefers the more spontaneous production process that alternative interfaces provide rather than the micro-design approach encouraged by Ableton.

But even for the artists at Artetetra, a given project will usually be run through one of the main DAWs at some point in the production process.

We hope you can see by now just how widespread the usage of DAWs has become for making music (especially “electronic” music) today. To begin making, say, a house track without a DAW you would need, at the very least, a drum machine, a synthesizer, a mixer and some kind of recording device, as well as the right wires and know-how to connect all this kit together. As Chad told us, it is “nearly impossible to get a modern song recorded, mixed, and mastered without running it through a DAW.”

Conclusion

We can see that the widespread uptake in the last two decades of Digital Audio Workstations like Ableton have seen them become essential infrastructure for contemporary music production. The combination of MIDI technology and the ability of third parties to create software add-ons for the most popular DAWs has embedded these workstations deep within the culture and practice of music-making in 2019.

As with most infrastructures, it can be hard to distinguish where infrastructure ends and what is simply built on top of it. Today, the average music producers toolbox is a constellation of various hardware and software. This has been true for a while but increasingly, the advent of DAW technology mas made computers the central command centre through which everything else runs in your average modern studio or home production suite.

One final note, however, should be that there is a trend that runs parallel but in a different direction to the ever-increasing computerfication of music. In what has been called the post-digital age, vinyl sales are up year-on-year and interest in more old-school, analogue music technologies is rising.

Major artists like Daft Punk have spoken out about the standardization they perceive as an effect of the increasing ubiquity of digital software (their 2013 album Random Access Memory, which featured songs like Give Life Back to Music can be seen as an embodiment of this critique).

Of course, resistance to the digital is as old as the digital itself—in the 90s J Dilla, one of the most influential hip-hop producers of all time, shaped the sound of the genre for years to come by switching off the quantization on his Akai MPC3000. The lazy, undeniably human texture of the resulting beats became his signature. Technology is always marching forward, but art and music just as often look back—and are by very definition a human affair.

References

Emusician. “Dada Life Sausage Fattener.” EMusician, 16 Sept. 2011, www.emusician.com/gear/dada-life-sausage-fattener

Galloway, Alexander. “Jodi’s Infrastructure.” E-flux, no. 74, June. 2016 https://www.e-flux.com/journal/74/59810/jodi-s-infrastructure/

Laukkonen, Jeremy. “VST Plugins Can Take Your Audio Mixes To The Next Level.” Lifewire, Lifewire, 24 June 2019, www.lifewire.com/what-are-vst-plugins-4177517

Leigh Star, Susan, and Geoffrey C. Bowker. “How To Infrastructure”. Handbook Of New Media, Leah A. Lievrouw and Sonia Livingstone, Sage Publications, London, 2006, Accessed 24 Oct 2019.

“Top 12 Most Popular Daws (You Voted For)”. Macprovideo.Com, 2019, https://www.macprovideo.com/article/news/top-12-most-popular-daws-you-voted-for.

Peters, Luke. “How Evolving Tech Has Changed Music Production.” Tech.co, 25 Jan. 2016, tech.co/news/music-production-evolution-2016-01

Plantin, Jean-Christophe, et al. “Infrastructure Studies Meet Platform Studies in the Age of Google and Facebook.” New Media & Society, vol. 20, no. 1, 2016, pp. 293–310., doi:10.1177/1461444816661553

Sethi, Rounik. “Top 12 Most Popular DAWs (You Voted For).” MacProVideo.com, 17 Apr. 2018, www.macprovideo.com/article/news/top-12-most-popular-daws-you-voted-for

Stone, Avery. “Mura Masa Will Teleport Your Brain into the Future of Pop.” Vice, Vice, 10 July 2017, www.vice.com/en_us/article/evdb4z/mura-masa-will-teleport-your-brain-into-the-future-of-pop

Yamaha, “The History Of The DAW”. Hub.Yamaha.Com, 2019, https://hub.yamaha.com/the-history-of-the-daw/