What is VK and why could it be a social media platform of the future?

What is the best and most well-known social network of all times? Most of the people would say Facebook. But what if somewhere in the land of forests, snow, and, of course, bears exists a social media platform, which has more than 100 million active users[1] and could be used not only for chatting with friends but also for listening to music, watching films, ordering food, paying bills and much more? Well, it might sound unbelievable, but this platform does exist. It is the Russian largest social network and it is called Vkontakte or VK.

What is Vkontakte?

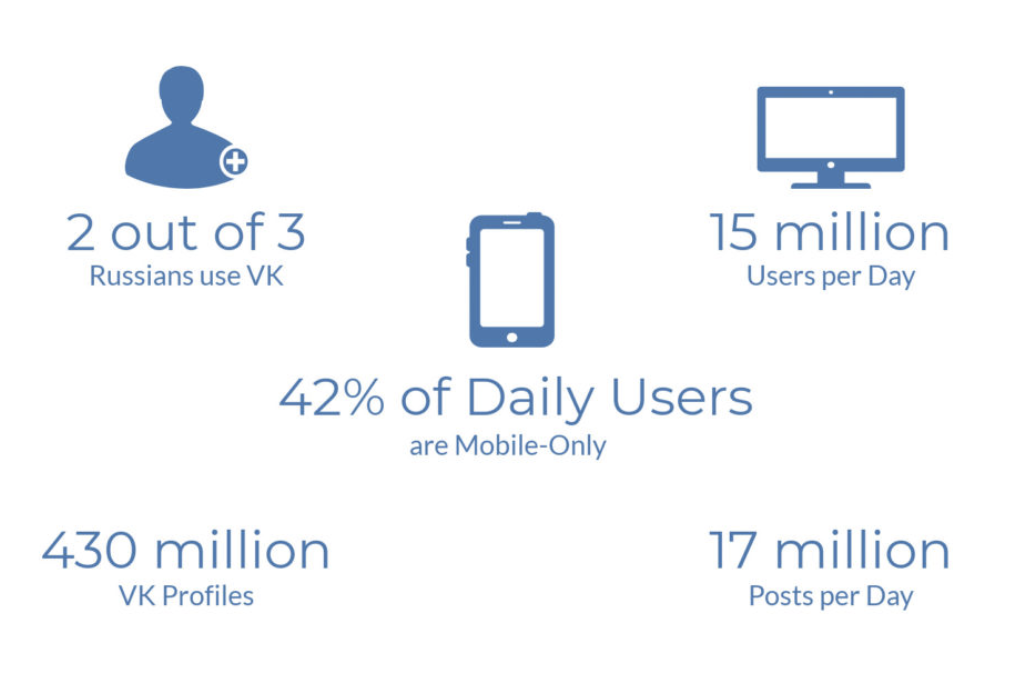

Vkontakte (Russian: ВКонта́кте, meaning “to be in touch”) was launched in September 2006 by Pavel Durov as a website, mirroring Facebook. With years it became extremely popular not only in Russia but also in other Russian-speaking countries and former Soviet Union republics: Ukraine, Belarus, Kazakhstan and Moldova. VK is one of the most popular websites in Russia[2] and is available in multiple languages, but it is predominantly used by Russian-speakers.

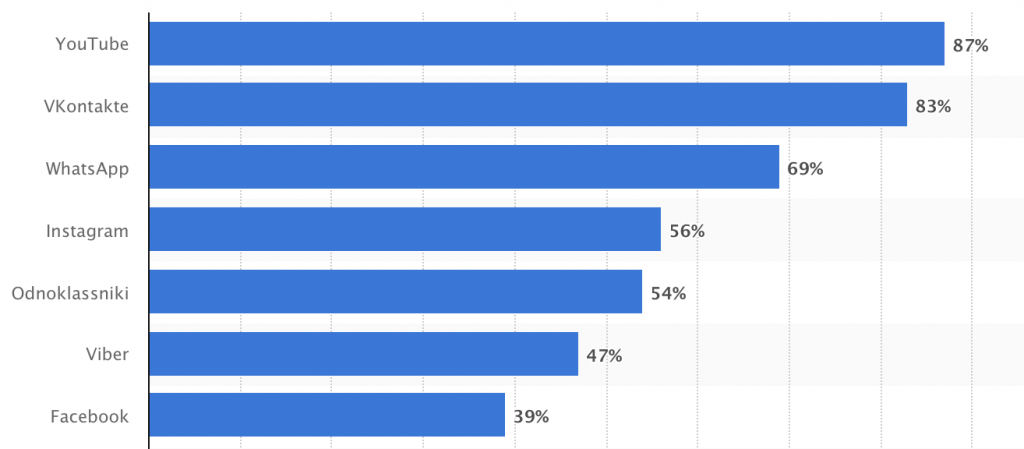

The website can be mistaken for Facebook because of its color scheme and design. It also shares the same services as most social networking sites from message contacts to browser-based games. However, according to the statistics, VK is used by Russian people more often than Facebook.

Why is it so and could VK be a social media platform of the future?

https://www.statista.com/statistics/1102127/russia-most-popular-social-media-for-news/

Shaping your web reality

Unlike Facebook, VK doesn’t insist on putting information about yourself. While creating an account a user has multiple standard things to fill up, for example, gender, age, relationship status. But there are also fields for whether you smoke, or if you’re military. You can even list your personal priority in a number of important areas: family and children? career and money? entertainment and leisure? fame and influence? improving the world? But none of these are compulsory, so the media platform doesn’t “discourage” you to have an empty profile (Davis and Chouinard, 2016). You can have your profile done even without giving the platform this information.

After registration Vkontakte will not annoyingly throw a list of possible friends to you in contrast to Facebook (Bucher, 2013) until you go to a special section on the website, where the Friend of a friend (FOAF) algorithmic technique (Bucher, 2013) could work to help a user make new connections via the social media platform. When a user already has a couple of people in his/her friend list, the friendship requires maintenance, as Bucher states in her text, which is true for VK’s friendships as well. All the interactions such as texting, liking and commenting on the activity of other users help the algorithms of VK to place this exact friend very first on your friend list and show you his/her activities more often.

Design

VK’s design could be understood intuitively and users don’t need to waste time finding necessary buttons. The interface design of Vkontakte does not change frequently (as Facebook does) and remains stable for years. “Website design we do not have to change, we like the minimalistic and simply constancy way it has looked at the beginning and also looks now,” as the supporting team of the Vkontakte approves (Baran and Stock, 2015).

Messaging

A user can text another user just in a frame of the VK mobile app or using a desktop version. No additional messenger apps are needed.

Private messages in VK can be exchanged between 2 individuals or within a group of 30 people. If photographs, audio files, videos, GIFs, documents and maps need to be attached, the sender can add up to 10 attachments.

Like Buttons

Here comes another thing lying in algorithms of the media platform, which functionality differs VK from Facebook. First of all, VK has only a “like” button and no expression faces as Facebook has. And secondly, when someone likes a post, comment, media, or link, the content will not automatically get pushed on the user’s wall but is first saved in the Favorites section, keeping it private until the user decides to make it public. This can be done by clicking on the “share with friends” button. A “like” button has “nothing to do with a specific button, rather than with the kinds of communicative practices (e.g. liking friend’s post) and habits they enable to constrain (e.g. liking and saving this post to Favorites section)” (Bucher and Helmond, 2018).

Privacy

Like most social networking sites, VK likewise empowers users to determine which content can be made available on the Internet or within the network. Pages and individual content are protected by granular security settings.

However, VK is not that good at protecting personal data. Several conflicts took place, for example, the leakage of data in 2016[3] or the scandal with Belarussian activist Kristian Shinkevich, who blamed the platform for storing the history of changing user’s name, list of deleted files and messages, IP addresses, removed posts and much more[4].

In addition, the platform stores images on a userapi.com domain and they remain there even after a profile is deleted.

“Just because the content is publicly accessible does not mean that it was meant to be consumed by just anyone” (Boyd and Crawford, 2012). However, unfortunately, it seems like it’s not applicable to the Russian biggest social network.

In 2019 a tool called SearchFace.ru was created by unknown authors. SearchFace allowed a user to upload a photograph, then it recognized a face in the image, and matched this face to its “twins” on VK.[5]

VK collects and stores user’s data to share it with third-party companies so as Facebook does. The platform “transforms virtually every instance of human interaction into data” (Poel, Nieborg, Dijck, 2019) which leads to specially created advertisements for each user popping out in a news feed. Basically, VK operates how Lisa Gitelman described: users and their actions became “a resource for data collection that vampirically feeds off of our identities and our “likes” (Gitelman, 2013). However, if use VK in a language other than Russian, the platform will barely show a user any advertisements at all!

Searching engine

VKontakte is well-known for its detailed profile information, which allows users to find each other easily and quickly. Users can be broken down and filtered by basic info, contact info, interests, education, work, military service and personal views. It’s possible to drill down as deep as views on smoking, views on alcohol or even political views. This helps not only users to find each other, but also the third-party companies to learn a lot about the audience and provide them with campaigns that they’ll be interested in.

Music and movies

VK lets you stream and share media files. And not only your personal photos and videos but also third-party music and videos. Normally, this kind of free file sharing is considered to be illegal, but no significant steps have been taken against these functions at this point in time. This is part of what initially set VK apart from other sites like Facebook – when Facebook is mostly focused on profile pages and status updates, VK is basically functioning as a Facebook-Spotify-YouTube hybrid!

Conclusion

Vkontakte contains a lot of engaging content, i.e., they provide a platform not only for communication but also for entertainment. Vkontakte is considered to be a “highly centralized platform” (Poel, Nieborg, Dijck, 2019) which develops really quickly. Besides extensive databases of audio and visual content, since 2019 it also gives access to users to activities of third-party companies (e.g. searching for a job with Worki service, order an Uber taxi, buy goods from Adidas, Apple, etc.) without leaving the VK platform. The incorporation of these and other stated above features makes Vkontakte a social media platform of the future more like YouTube, Netflix, Spotify, and WhatsApp all in one, with an interface highly reminiscent of Facebook.

On the other hand, the privacy of users’ data still remains uncertain and makes some users quit the network because of its insecurity.

To sum up, I would say that VK is a Russian product and definitely a source of some national pride. Russian people are used to using this super handy and user-oriented platform for many purposes besides communicating with friends and privacy problems probably don’t overweight the pros of the network. As well as, nowadays there can be seen an evident tendency for centralization (having many providers on one platform) and that is why VK can be consedered to be the social media platform of the future. Or at least a great model for that, which still needs some improvements.

With all that being said, I think, that in the world of new media VK is an underestimated and sadly yet unknown Russian social media giant with more advantages than disadvantages which the world is still to discover.

[1] https://expandedramblings.com/index.php/vk-statistics-facts/

[2] https://www.alexa.com/topsites/countries/RU

[3] https://thehackernews.com/2016/06/vk-com-data-breach.html

[4] https://advox.globalvoices.org/2018/08/30/is-russian-social-media-giant-vkontakte-sidestepping-the-gdpr-one-user-is-trying-to-find-out/

[5] https://www.bellingcat.com/resources/how-tos/2019/02/19/using-the-new-russian-facial-recognition-site-searchface-ru/

Bibliography

Davis, Jenny L and James B Chouinard. 2017. Theorizing Affordances: From Request to Refuse. Bulletin of Science 36(4): 241-248

Bucher, Taina. 2013. The Friendship Assemblage: Investigating Programmed Sociality on Facebook. Television & New Media 14(6): 479-493.

Katsiaryna S.BARAN, Wolfgang G. STOCK. Acceptance and Quality Perceptions of Social Network Services in Cultural Context: Vkontakte as a Case Study, 2015 https://www.phil-fak.uni-duesseldorf.de/fileadmin/Redaktion/Institute/Informationswissenschaft/heck/Baran___Stock_Vkontakte.pdf

Bucher, Taina and Anne Helmond. 2018. The Affordances of Social Media Platforms. In: Burgess, J, Poell, T, Marwick, A (eds.) The SAGE Handbook of Social Media. London and New York: Sage, 233-253. (preprint)

Boyd, D. & Crawford, K., 2012. Critical Questions for Big Data. Information, Communication & Society, 15(5), pp. 662–679.

Poell, Thomas, David Nieborg and José van Dijck. 2019. Platformisation. Internet Policy Review 8(4): 1-13.

Gitelman, L. (ed.) 2013. Raw Data Is an Oxymoron. Cambridge: MIT Press. Introduction chapter.