Artland: A platform-analysis on the democratization of the art world fostered by an online art market

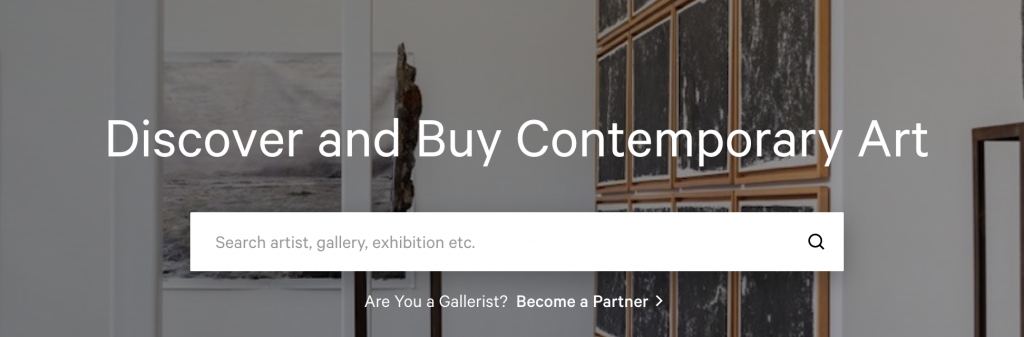

In a more and more digitalized world and with the rise of COVID-19, cultural institutions like galleries and museums have been constrained to explore alternative digital areas, and so does the art market. But how does this digitalization of the art market contribute to democratization of the art world? Can online art platform Artland be perceived as a blueprint towards future art platforms?

Introduction

Nowadays a lot of practices have shifted from an offline environment to an online environment. Nevertheless, cultural institutions, like galleries and museums, have stayed predominantly physical atmospheres where in-person connections are highly valued. But with the rise of COVID-19, these institutions have been pressured to delve into alternative digital areas.

In the art gallery sector, there has been a substantial response to the virus outbreak through the enhanced use of online viewing rooms (Pogrebin). Whereas some question the use of online platforms to see and buy art, as it would perhaps diminish the experience, relative to a live encounter (DebatingEurope), this time of crisis brings forward the benefits that online art platforms have and how they foster potential democratization in increasing access and valuing openness and transparency (Vukovic).

An online art market that based their company on these latter principles of creating more democracy and transparency is Artland. Founded in 2016, Artland wanted to build a social marketplace for the contemporary art world and their key players, namely galleries, professional collectors, art-lovers, while also hoping to address new generations of art buyers, where online art is viewed, shared, bought and sold, through means of 3D-scans and VR, amongst others (Lomas).

By taking Artlandplatform as the object of study and conducting a platform-analysis, we aim to look at the achievable contribution of Artland and the “platformisation” of arts and galleries, to the democratization of art fostered by the online art market. We therefore analyse the following research question:

Does the app Artland and the platformisation of arts and galleries contribute to the democratization of the art market?

Our understanding of “platformisation” is based on the definition by Poell et al. “the penetration of infrastructures, economic processes and governmental frameworks of digital platforms in different economic sectors and spheres of life, as well as the reorganization of cultural practices and imaginations around these platforms.” (5-6)

Methodology

Examining how a platform such as Artland could have an effect on the democratization of art requires a robust framework, due to the complexity of the medium. We will use the “platform-analysis” by van Dijck which combines the Actor Network Theory with Political Economy (25), to examine how the specific actors and economic and technical choices of Artland shape the power dynamics of the platform. This approach will help us form an understanding of whether the art market is effectively democratized on Artland.

The first part of van Dijck’s model, the “techno-cultural construct”, examines “technology, users and content” (28). Examining these three concepts will help us to explore how these different actors of the platform interact with each other. The second part of the model focuses on the “socio-economic structures” of the platform and examines “ownership status, governance and business models” (van Dijck, 36). This section of the analysis will examine what is behind the materiality of the platform, and how the systems of power behind the platform are shaped. From this discussion, we will develop a nuanced understanding of Artland as a platform, draw conclusions, answer our question, and pose new ones for further study.

Analysis

Technology

According to Gillespie the term platform carries different sets of meanings: platforms are computational and architectural concepts, but they can also be understood in a socio-cultural and political sense: as stages and technological performative infrastructures (349-350). Scholars have described how platforms have become intermediaries, setting the stage for actions to unfold through ordered emergence and shaping the performance of social acts instead of only facilitating them (Bratton 17). The technology of a platform plays an important role in this process, as Van Dijck describes it: “Platforms are the providers of software, (sometimes) hardware and services that help code social activities into a computational architecture” (Van Dijck 29). To define the intermediary role of Artland, it is helpful to analyse the software and services of the platform.

Artland does not provide insights into the accounts of the galleries with memberships, so we will focus on the user experience (art lover, collector and buyer). Artland has a website and mobile application for discovering and buying art online, that can both be used with or without an account. As aforementioned we will touch upon the (meta)data, algorithm, protocol, interface and the defaults of the platform.

(Meta)data

Different types of data are collected in the app. When registering users have to provide personal information such as their names and country of residence, while also linking their account to either their email or e.g. their Facebook-account. Other types of data are images, selected art-preferences and metadata such as the artists and art-style of a painting.

Algorithm

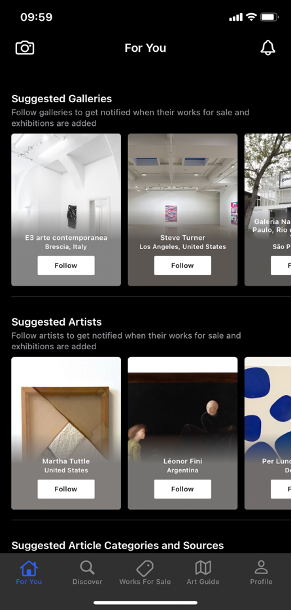

The algorithm of Artland is visibly at work as soon as users log in. All the suggested categories on the homepage change from for instance the latest exhibitions to suggested exhibitions or exhibitions that you follow. These suggestions are based upon the set preferences in the user’s profile, the galleries they follow, the art they view and other user behaviour.

Protocol

Within the app, there are certain protocols to follow. For example, when users register, they have to fill in their names and choose their preference in art style. It is also expected from users to follow and connect with galleries, other collectors and artists. On every shown profile of a gallery or collector, there is a large follow button. Users also get notifications that will encourage users to follow other users to improve their personalized feed, steering them to connect and provide more data about their preferences.

Interface

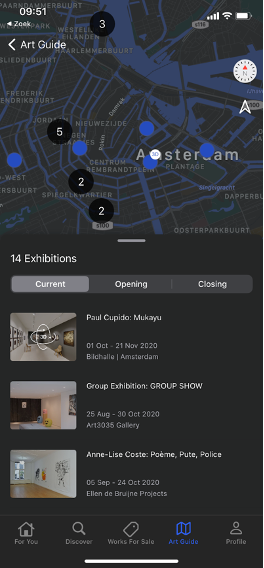

Van Dijck describes interfaces as an area of control where “coded information gets translated into directives for specific user actions” (31). The interface of Artland is divided into five categories, that all focus on another feature of the app: For You, Discover, Works for Sale, Art Guide and Profile. From these categories and their interface four main user actions can be disseminated: connecting with other users, discovering galleries and buying and uploading art. For example, in the app users constantly see a camera icon that invites them to upload pictures of their own art collection.

Default

There aren’t many settings that are automatically assigned when installing the application, because most technical features can be used by non-members. The set art preferences are one of the few defaults that are pre-set, where no preference has been selected thus showing all different types of art.

Users

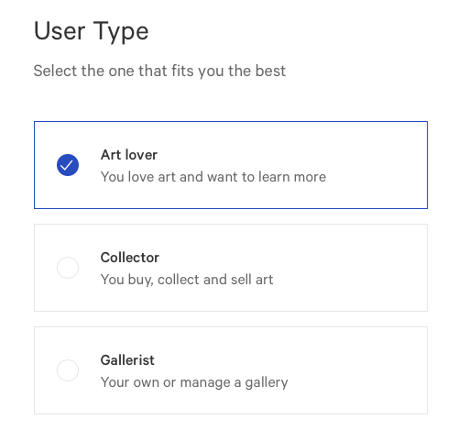

The users of a platform are a vital factor for a corporation to grow and operate. In 4 years, Artland has gained over 65,000 users across the globe (Artland). The platform provides people to connect, discover, sell, and buy art pieces. In fulfilling their goal to connect and create the world’s largest community of collectors, Artland targets three types of users: Art lover, Collector, and Gallerist. Upon signing up, users are to choose which user type fits them best. Unlike most platforms that curate their audience to either one particular niche such as Facebook, having the same feature and accessibility for user types, Artland offers a more tailored option. The user’s activity on Artland may differ, but all users have the commonality of appreciating art.

The first user type, Art Lover, is dedicated to users who want to explore and discover art through online art exhibitions, locate close by galleries, and follow art-related news. The sign-up process includes a selection of art style preferences for the user’s personalized feed. The Collector seeks to find art pieces, potentially buy it, and is given the platform to sell their art as well. Lastly, Gallerists are for galleries who want to gain more exposure and accessibility globally. The business model will further explain the service.

Content

The content of Artland revolves around artworks and online exhibitions. On Artland users can buy various types of art: from books and animation to sculptures and paintings. The way these different forms of art are presented has been standardized, meaning that all of the artworks are captured in pictures (even the videos). This standardization of content helps with setting the technical infrastructure of the app, making it easier for the developers to categorize and filter and helping users to find their content. Other forms of content are the online exhibitions, which can be viewed by users in pictures, 3D or in virtual reality. Whether an exhibition is viewed in 3D or VR depends on the membership that a gallery has. Finally, the feature Art Guide can also be seen as a form of content, used by some members as a calendar and map for current exhibitions to visit in real life.

Ownership

Artland is a venture capital with the latest investment of $1,000,000 from angel investors. One of the investors, Mikkel Hansen, was motivated to be involved as his vision aligns with the founders. He states that “the art world seems to be so complicated — especially if you’re a newcomer who wants to buy an art piece, it’s a challenge to find information about the artist, the price range and so forth.” (qtd in Ohr). The gap in the digital art niche fuels investors to financially support the missing component of the art world. Through the investment of $1,000,000, Artland is also viewed as a potential flourishing venture.

Nevertheless, the concept of selling art online is not unique. Christie’s and Sotheby’s are both British found art auctioning corporations who have extended their physical auctions to digital platforms (Graddy). Neither is the notion of virtual museums nor finding art inspiration online unique. Partnerships between museums and Google Street View have been increasing since their agreement in 2011 (Haigney). In addition, platforms such as Pinterest and Instagram have satisfied most users looking for inspiration. Yet, Artland has been able to break through from existing platforms due to the successful integration of various elements in one platform.

Governance

Governance examines rules that are drawn up for users on the basis of social and technical protocols (van Dijck, 38).

Artland uses different forms of governance based on two types of users: non-members and members. Non-members can visit the platform without signing up but do have to agree with Artland’s cookie policy: data on location and IP-address will be processed. When requesting information about or purchasing an artwork as non-members several additional data will be gathered, such as telephone number and payment information. Members sign up through email, Facebook, Apple or Google account. When signing in, the user is automatically agreeing with the Term of Service (ToS). Subsequently, the user is asked to create an account, personalized by requirements (e.g. name, country of residence) and non-requirements (e.g. style, artists, galleries). This personal data is processed, along with any other activity the user might perform like, comments on a post, followers, etc.

When it comes to the usage and transfer of the user data,Artland states it may disclose or transfer personal data to vendors, business partners or other collaborators for business purposes, when relevant. Transfer personal data to third countries outside of EU/EEA will be carried out according to applicable data protection legislation.

Additionally, Artland has implemented measures to protect personal user data and ensure user rights. The legal base for converting of personal data, used here, is the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) framework.

Business model

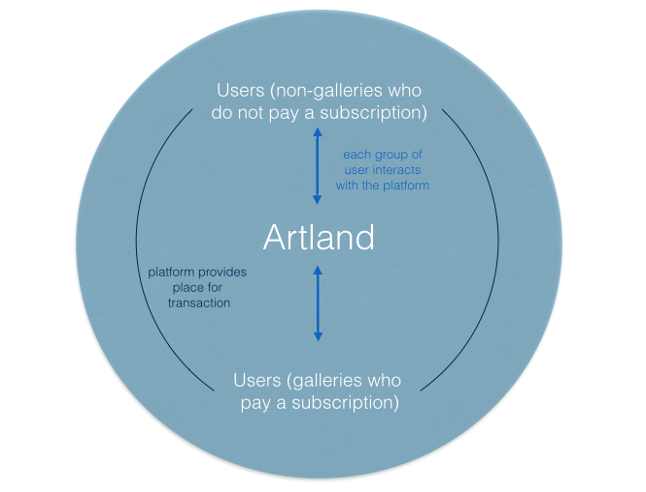

Artland’s role in democratising art is limited and propelled by the fact that it is a platform with a platform business model. Poell et al. note that platforms gain a strong market position through being “multi-sided markets”, where they process transactions between other parties (Poell et al.). Indeed, Artland characterises its role as simply a “venue” in its User Agreement: “While Artland helps facilitate transactions that are carried out on the Artland Platform, Artland is neither the Purchaser nor the Seller of the Seller’s items” (“User Agreement”).

Fig 1: The multi-sided market model of Artland’s platform.

Graph based on “Multi-sided platforms”. Harvard Business School. 16 March 2015, p 6.

Multi-Sided Market of Artland

Multi-sided markets rely also on the process of “network effects”, where platforms offer access to the platform for free, to grow a user base who can be marketed for future transactions (Poell et al.). As the platform is free, and transactions are made easy, the number of users on the platforms grows, increasing the platform’s influence in their market (Poell et al.). Artland’s business model is to collect subscriptions only from gallery users, while other users use the service for free. Galleries must pay between sixty and five hundred and twelve euros a month to put their works on Artland (Artland). Through this business model Artland appears to offer art for free, but they actually offer their users as a marketable audience to galleries.

Discussion & conclusion

Techno cultural construct

Within the Artland application the algorithm, protocol and interface are the most defining technical features. These features direct the users of the platform to carry out a certain conduct, that is focused on discovering and buying of art and creating an online art community. The platform therefore plays a role in shaping the performance of discovering and collecting art, also translating these social activities into computational forms. A limiting aspect in our research into the technology of the platform is that we haven’t been able to gain insight into the accounts and the technologies used by the galleries, which also detracts the transparency claim of the platform.

Users are able to decide how they want to operate and use Artland as a platform. The three different options give users the freedom to curate the platform to their own needs. However, this is also a limitation as users can only be categorized into one of the three groups. Instead of diversifying, an identity construct remains and is reinforced with users who have become members through signing up and non-members. It is also critical to acknowledge that this research was only limited to a user point of view and not galleries. Therefore, further research on all different aspects of Artland needs to be scrutinized before claiming the democratization of the digital art world.

Artland offers two sorts of content: the artworks and the online exhibitions. On both forms of content, a certain standardization has been applied, that helps developers to categorize and filter, also making it easier for users to find what they’re looking for. For online exhibitions Artland also offers 3D or VR visualizations to galleries, including it in their business-model. In terms of the ownership of the content, Artland claims that all texts, images and graphics on the platform are owned and controlled by Artland (Terms of Services 2020). It’s not clear what this exactly entails for galleries and artists in terms of ownership, because Artland doesn’t disclose anything about their contracts with them.

Socio-economic structures

Even though the aim of Artland was to involve a large scale of people into the art world. Artland remains to appeal to art enthusiasts in the realms of users and investors. The start-up company is predominantly financially supported through aesthete, which may become a challenge when Artland chooses to further expand. The openness of Artland to partnership and angel investors illustrate their keenness into supporting the democratization art, nevertheless, the specific niche Artland represents may lead to de-democratization.

Technology can enhance or undermine democracy depending on the use and who controls it. Despite the data on Artland being processed based on the GDPR, the ToS, as Van Dijck (38) argues, construct a grey area. Helen Nissenbaum identifies here the ‘transparency paradox’ (in Yeung 126). In this case, the GDPR requires that individuals must be informed about their data being collected and shared and users have to agree before they can use the website but providing the level of detail needed for these terms can be quite overwhelming and detailed. But then, simplifying these terms would perhaps fail to provide sufficient detailed information and undermine people to make informed decisions.

Van Dijck notes that platforms have become “mediators in the engineering of culture”, through business models which focus on extracting profit from their role as a place to access a product (39-40). Thus, Artland’s apparent democratization of art is fundamentally linked to the sale of art, and platform economics, which presents the user as a marketable audience to Galleries. Artland gives users access to art they may otherwise not have had, in a highly commodified space, where they too, are commodified as a market to other users.

Art has shifted from a more private sphere to a somewhat more public sphere through digitization, and the art market follows with more openness and democratization. As shown in the case study we can see how platform technologies can reshape and reimagine what the art world can be, including increasing accessibility. Through examining Artland’s techno-cultural construct and socio-economic structure, we can conclude that Artland is an exemplary blueprint towards future art platforms. The centralization and inclusion of many different features create new opportunities for a larger and remote audience. Nevertheless, it is also crucial to consider the limitations, such as the ‘transparency paradox’ of governance and questions regarding who owns the art, platform economics, and how accessible it is for artists to showcase their art.

. . .

Bibliography

Artland. Artland Announces U.S. General Availability, Bringing the Art World Closer and Making It More Accessible than Ever. 5 Feb. 2020, www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2020/02/05/1980210/0/en/Artland-Announces-U-S-General-Availability-Bringing-the-Art-World-Closer-and-Making-it-More-Accessible-than-Ever.html.

Bratton, Benjamin H. The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2015. Print.

Debating Europe. “Does viewing art online diminish the experience?”. 2016. Debating Europe. 7 October 2020. https://www.debatingeurope.eu/2016/03/31/viewing-art-online-diminish-experience/#.X4b0kngzblw.

Gillespie, Tarleton. “The Politics of ‘Platforms.’” New Media & Society, vol. 12, no. 3, May 2010, pp. 347–364, doi:10.1177/1461444809342738.

Graddy, Kathryn. “Sotheby’s and Christie’s Expand Private Sales.” VOX, CEPR Policy Portal, 21 Sept. 2019, voxeu.org/article/sotheby-s-and-christie-s-expand-private-sales.

Haigney, Sophie. The Dizzying Experience of Visiting Virtual Museums. 1 Apr. 2020, www.artnews.com/art-in-america/features/virtual-museum-tours-google-1202682783/.

Lomas, Natasha. Artland Is a Social Art Market That Connects Galleries and Buyers. 17 Nov. 2017, techcrunch.com/2017/11/17/artland-is-a-social-art-market-that-connects-galleries-and-buyers/.

Hagiu, Andrew and Julian Wright. “Multi-sided platforms”. Harvard Business School. 16 March 2015.

Ohr, Thomas. “Copenhagen-Based Artland Receives $1 Million to Further Boost the User Base of Its Art App.” EU, 13 Mar. 2018, www.eu-startups.com/2018/03/copenhagen-based-artland-receives-1-million-to-further-boost-the-user-base-of-its-art-app/.

Poell, Thomas. & Nieborg, David. & van Dijck, J. “Platformisation.” Internet Policy Review 8.4 (2019): 1-13. 21 September 2020. https://pure.uva.nl/ws/files/43149747/Poell_Nieborg_Van_Dijck_Platformisation_2019_.pdf

Pogrebin, Robin. “Art Galleries Respond to Virus Outbreak With Online Viewing Rooms.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 16 Mar. 2020, www.nytimes.com/2020/03/16/arts/design/art-galleries-online-viewing-coronavirus.html.

“Terms of Services”. Artland. 2020. 20 October 2020. https://www.artland.com/legal/tos#using

“User agreement”. Artland. 2020. 19 October 2020. https://www.artland.com/legal/tos

van Dijck, Jose. The Culture of Connectivity: A Critical History of Social Media. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013. Web.

“Visual Traceroute”, Digital Image. GSuite Tools, GSuite.Tools. Web. 18 October 2020. https://gsuite.tools/traceroute

Vukovic, Jovana. “Will Online Art Viewing Rooms Survive Coronavirus?”. 2020. Widewalls. 14 October 2020. https://www.widewalls.ch/magazine/online-viewing-rooms-art-galleries

Yeung, Karen, “‘Hypernudge’: Big Data as a mode of regulation by design” Information, Communication & Society 20.1 (2017): 118-136. 12 October 2020. https://www-tandfonline-com.proxy.uba.uva.nl:2443/doi/full/10.1080/1369118x.2016.1186713