“Stop licking the boots and start marching them” – An exploratory research proposal into peer-to-peer political discussion on TikTok

by: Samuel Vitikainen, Max Buzzell, Loulou de Regt, Lotte Timmermans

For people over 24, and some people under 24 too, TikTok constitutes a phenomenon as alien as Narnia: a strange world where the rules are difficult to understand. To an outsider, TikTok is probably known as the dance app where adolescent boys and girls can share their moves. However, since its worldwide debut in 2017, more users flocked to the app and TikTok evolved into more than a platform to shake your booty. In the light of the 2020 US elections, TikTok users managed to sabotage Trump’s rally in Tulsa by signing up for seats and not showing up. The prank was entirely organised by K-Pop fans and TikTok users. For this project, we decided to step through the wardrobe, and delve deeper into political TikTok to uncover some of its mysteries.

Once you take that step through the wardrobe, you will notice that TikTok is inhabited by a lot of heterogeneous peoples. One of these hubs is political TikTok, where young people use the platform to speak up about their views on contemporary political debates. Within this sector, there is again a lot of difference in ideologies, topics, and trends. However, political TikTok remains largely uncharted territory in academics.1 Hence, the aim of this blog is to explore some of the mechanisms in the land of political TikTok and to carve a path towards more research into TikTok’s affordances, the logic of connective action, and the political culture on social media in general. Therefore, we would like to propose a preliminary research question for this investigative blog: How does TikTok afford peer political information sharing? As a case study, we will focus on US-based leftist TikTok.

First, we will introduce you to the academic context concerning this topic and highlight the connection between affordances, political activism and the logic of connective action. Then we will explain TikTok’s relevance as a political arena, and continue with proposing possible methods for researching this matter. The methods chosen are the walkthrough method by Light et al, which will create insight in the affordances of TikTok, and Machin and Mayer’s multimodal discourse analysis in order to examine the connective action and vernaculars on TikTok.2

Political Activism on the Internet

Political activism online, like any form of the human communicative and interactive agency, is governed by the materiality of the platform that facilitates it.3 A specific kind of dynamic, condition and culture is enabled by the deliberate structure of seemingly taken-for-granted assortments of technical features.4 Mundane low-level affordances, such as ‘follows’, ‘shares’ and ‘comments’, contribute to the cultivation of those profound high-level affordances which shape the user’s experience of sociality within a platform.

A fundamental shift in online political engagement was prompted by the simple affordances that enabled one to ‘share’ their ideas through ‘personalised’ digital communication.5 While groups were at one point largely mobilised as a collective under traditional political authority, Bennett and Segerberg point out a shift toward groups of motivated individuals organised by digital media as loose networks. By forming horizontal-oriented social networks, digital media effectively removed the need for hierarchical political coordination. Individuals retain their enthusiasm for social issues as they are able to participate in political information sharing within their own personalised expression. Instead of operating as collectivist movements, this logic of connective action allows for the emergence of individualised flexible social networks.6 Technologically-enabled, their effectiveness as organisations of individuals emphasizes the role of digital media as an organising agent as well as a specific environment that contributes to the emergence of specific socio-political dynamics.

However one should not understand this tension between human agency and materiality as entirely asymmetric.7 While technology functionally enables and constrains, communicative affordances recognise that these confines may apply differently between individuals. One’s ability to perceive, competently execute, and legitimately perform possible actions is within the agency of the individual.8 While these possible actions and conditions are still shaped by affordances, our attention to platform design should consider the identities and intentions of the users. Both of these concepts shape political communication on social media and will be considered in our research as we explore political activism online.9

TikTok and Politics as Entertainment

The social media app TikTok, designed for creating and sharing short-form videos, is becoming increasingly popular. The app was launched by the Chinese company ByteDance in 2017, and in September 2020 it was the most downloaded non-gaming app worldwide with over 61.1 million installs.10 TikTok has a reputation for being popular among teens, with 32.5% of its users ageing between 10–19. The app offers a unique format, best described as memes-as-videos, backed with music and other soundbites. The content can be standalone videos, with trends and challenges that are endlessly reproduced, or users respond to other videos in the form of greenscreen effects, or duets, where the reaction appears next to the original video.11 When scrolling through the ‘for you’ page, TikTok’s algorithmically determined, infinite-scroll feed, you get the sense of a community of irreverence with a particular focus on adorableness and lighthearted humour.

NOTE: clicking on the image will refer you to en external site (YouTube)

However, the For You page is different for every user. TikTok explained in a blog post how its algorithm works: based on your interactions with the app, your likes, follows, preferences, and hashtags, the algorithm recommends videos you may be interested in in your feed. If you show any interest in politics, you will discover a large political world in TikTok’s ecosystem.12 The company wants to stay out of politics, banning political campaigns and focusing on their mission to “inspire creativity and bring joy.”13 It is however unavoidable that users will express their views, engage in political discussions, or update their peers on daily political news on a large social media platform.14 Young people can be politicized on TikTok in both directions of the bipartisan US political spectrum, as they are “searching online for a political identity.”

As TikTok is relatively new, not a lot of research has been done on how political discussion is organized on the app. In line with the logic of connective action, young people seem to engage with politics online in a highly individualized and ad hoc issue-based way.15 On TikTok this mechanism is emphasized strongly. The interactions are organized horizontally, so instead of interacting with politicians or experts, TikTok users stay informed through peer-to-peer contact.16 Cross-partisan interactions do happen but tend to have a polarizing effect.17 As Medina Serrano et al. demonstrate, TikTok users perform politics based on personal opinion and interaction through reactions and duets.18 Political performativity becomes filtered through and shaped by the mechanism of entertainment—politics as entertainment.19 On TikTok, users are vying for our attention to become the next political star.20

For this project, we will do exploratory research (with a call for further investigation based on this research proposal) into a specific sector of political TikTok in order to investigate the online phenomenon of politics as entertainment. By investigating how TikTok affords peer political information sharing, we hope to contribute to an understanding of the logic of connective action, as well as the meaningful communicative symbols and interactions of political TikTok users. In order to narrow down the scope for this project, we focus on US leftist TikTok videos as a case study.

Methodology

This project will employ two different methodological approaches: the “walkthrough method” and multimodal discourse analysis.21, The walkthrough method is particularly valuable for this project, as limited research on the affordances of TikTok require us to examine the app in its mutual shaping possibilities in order to begin to understand how users of the app might utilize digital vernaculars to educate peers and demonstrate a logic of connective action.

The walkthrough method encourages a definition of affordances that understands the cultural and political implications of what is allowed, encouraged, and discouraged within the possibilities of user action on an app. In the process of “walking through” an app (from registration to mimicking daily use, to closure) Light et. al. proposes that researchers focus on three aspects of the app: the vision (purpose, target base, scenarios of use), the operating model (business strategy and revenue sources), and governance (rules and guidelines that restrict or allow user interaction).22 By using this method in the context of this project, we can establish what TikTok affords its users. Rather than being a purely descriptive depiction of TikTok, the walkthrough method will help us contextualize the affordances of TikTok within the sociocultural environment of its creation and use.

Once we have established this cultural understanding of the affordances of the TikTok platform, we will approach the second part of our research question, peer political information sharing, through a multimodal discourse analysis of select leftist TikTok videos. Multimodal discourse analysis focuses not just in denaturalizing textual data, but also in examining audio-visual elements as part of the “text” of new media.23 We will be using multimodal discourse analysis to examine how TikTok users speak about certain topics (how they use the vernaculars of the platform), how they present ideas visually, and what memetic audio or visual elements are included

The use of multimodal discourse analysis in examining peer political information sharing will allow us to follow up on the mix of cultural and technological understandings of TikTok’s affordances gained by the walkthrough method. These two methods will provide us with a holistic approach wherein we examine how the app affords certain actions to the user, how those affordances are culturally created, and how users create content while interacting with those affordances, using specific vernacular linguistic and audio-visual tools to educate and connect.

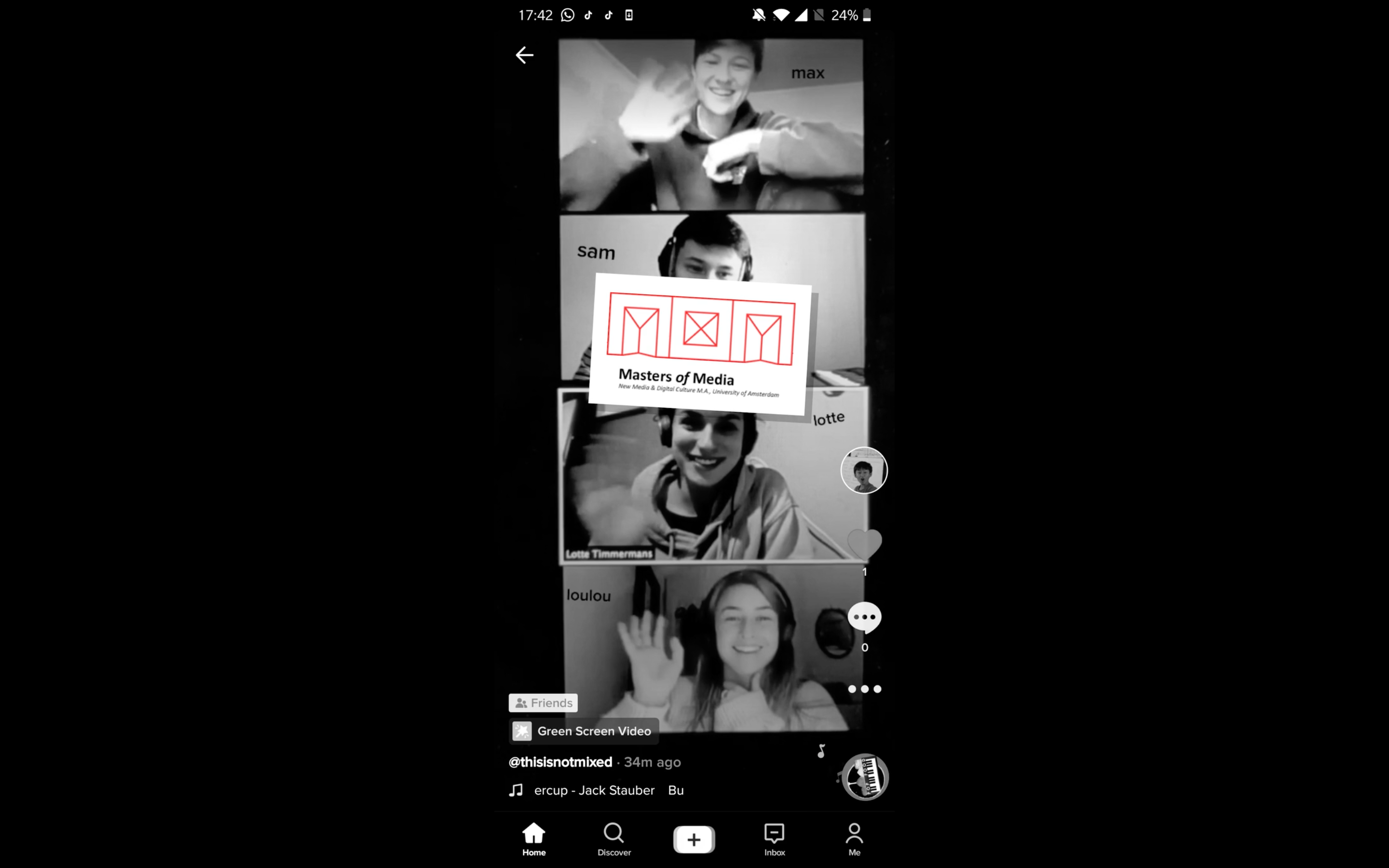

NOTE: clicking on the image will refer you to en external site (YouTube)

Analysis

The walkthrough method by Light et al. consists of several elements in order to examine what TikTok affords its users. In this section we will discuss the analysis of TikTok with the help of this method, then we will use the outcome of this analysis to continue with the multimodal discourse analysis. First, the environment of expected use needs to be determined, which includes gaining insight into TikTok’s vision, operating model and governance.24 TikTok’s vision is stated on their website: “TikTok is the leading destination for short-form mobile video. Our mission is to inspire creativity and bring joy.”25 Hence, the platform should afford creativity and joy. Looking at the operating model of TikTok entails diving into the business strategy and revenue model of TikTok. TikTok generates revenue through ads and from the sale of virtual goods such as emojis and stickers to fans. TikTok also has its own digital currency, namely coins, which are purchased with actual money and TikTok takes a percentage of that transaction. Lastly, the governance of the application entails the managing and regulation of users.26 So, what does TikTok allow its users to do on the platform? For example, it allows (or affords) its users to post videos, however, they cannot share pictures.

Besides the environment of expected use, Light et al. also introduces a technical walkthrough. “The technical walkthrough is the method’s central data-gathering procedure. It involves the researcher engaging with the app interface, working through screens, tapping buttons and exploring menus.”27 This requires the researcher to take on the role of a TikTok user with an analytical eye. Features that we should pay attention to can be categorized within these four ‘mediator characteristics’: user interface arrangement, functions and features, textual content and tone, and symbolic representation.28 For TikTok, this includes liking, sharing and comment buttons, where they are placed, and what is easy to access (for example).

The sample that was selected for this proposal consists of TikToks that all four group members collected by browsing specific leftist hashtags (#leftist, #socialist, #socialism, #politics, #biden, #bernie, #liberal, #settleforbiden, #communism, #lgbtq, #queer theory, #progressive, #left) and curating our For You Page. Each group member then added their findings to a spreadsheet. This allowed us to come up with a diverse sample (each of our For You Page algorithms being different) and pick out five videos that represented the range of what we collected in the spreadsheet.

In this section, we will summarise our analysis of the five selected videos according to the criteria of the multimodal discourse analysis. We found some preliminary themes that we can use to show that this research proposal should be further extrapolated. These themes are not mutually exclusive.

Theme 1: Sarcasm (tone)

The first theme that presented itself within our sample relates to the ‘tone’ of the videos. Tone refers to the general character or attitude portrayed in the TikTok content. Attributes that belong to the category ‘tone’ are sarcasm, irony or a lighthearted tone, on which we will focus on this theme. These rhetorical devices are used to give light to a heavy (academic or political) topic. An example of this we found in our sample is a TikTok by user @helloiamanegg. In the video, the user addresses capitalist exploitation in the form of a song accompanied by her playing the ukulele. The ukulele can be associated with happiness due to its sound, however, the user addresses serious political issues. Hence, this can be interpreted as ironic to stress the importance of the matter and what is currently ‘wrong’ with society according to the user.

Theme 2: “Internet Ugly Aesthetic”

In Literat and Van den Berg’s explorations of the sub-Reddit r/memeeconomy, they highlight the “internet ugly aesthetic” that characterizes “authentic” (less mainstream) subcultural memes.29 For Literat and Van den Berg, the look and feel of the “ugly internet aesthetic” are juxtaposed against normie memes—those memes that reach the mainstream and are therefore less valuable as a marker of Internet subcultures. The visual and memetic tools used by the creators of our small sample of five select leftist TikToks reference this style of subcultural vernaculars. User @anarchava sits in the car, recording on the phone with one hand while explaining, lecture-style, how anarchy and parenting line up historically. Users @antifa_greg_heffly, @deuce309, and @thebroliatriat address viewers by handheld phone in mirror reflections. The technical affordances of TikTok, allowing users to greenscreen another video or photo and add text for titles is also used widely by these five creators, positioning the aesthetics of the videos as part of the platform, while also, content-wise, being less mainstream than the TikTok dance crazes.

Theme 3: Memes (references to Internet tropes)

These technical affordances of TikTok work to create aesthetics, tropes, and memes that position the videos on the platform as unique. The five users we selected sarcastically play with the style of Internet (and specifically TikTok) memes to surprise viewers with hefty academic or political concepts. For example, user @antifa_greg_heffly uses the “hey, friendly reminder” TikTok trope, and in an ironic turn, reminds viewers that they “are closer to being homeless than you are to being a billionaire and that’s on the absorption of the petit-bourgeois and the proletariat and the tendency of the rate of profit and wages to fall,” encouraging them to “stop licking the boots and start marching them.” User @thebrolitariat uses the technical affordance of TikTok’s audio meme trend to share riot packing essentials (encouraging defunding the police), while the “Gravity Falls Intro (Electro) – Blaze Blue,” a song tied to the “___ 101” trend plays in the background.

Conclusion

This brief research proposal allows us to consider how understanding the technical affordances and the cultural setting of TikTok as a platform can help us understand how specific vernacular and memetic themes are used by leftist creators to spread information in an almost subversive way—following meme formats with the sarcastic twist of a hefty academic touch. If this research proposal is expanded, the combination of defining affordances through the walkthrough method with a multimodal discourse analysis can be used to better understand how TikTok affords peer political information sharing. With this blog, we found that there is still a lot of research to be done into left-centered TikTok. We propose more systematic research into this phenomenon, specifically a rigorous multimodal discourse analysis to understand the mechanisms and culture of leftist TikTok. Such a research would need a large corpus, but luckily more and more content is being made every day. We hope that with such research, we would gain more insight into the real world effects and societal impact of TikTok.

References

[1] Juan Carlos Medina Serrano, Orestis Papakyriakopoulos, and Simon Hegelich, “Dancing to the Partisan Beat: A First Analysis of Political Communication on TikTok,” in 12th ACM Conference on Web Science (WebSci ’20, Southampton, UK: ACM, 2020), 257,https://doi.org/10.1145/3394231.3397916.

[2] Ben Light, Jean Burgess, and Stefanie Duguay, “The Walkthrough Method: An Approach to the Study of Apps,” New Media & Society 20, no. 3 (March 2018): 881–90, https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816675438;

David Machin and Andrea Mayr, How to Do Critical Discourse Analysis: A Multimodal Introduction (Los Angeles: SAGE, 2012).

[3] Medina Serrano, Papakyriakopoulos, and Hegelich, “Dancing to the Partisan Beat,” 257–66;

Taina Bucher and Anne Helmond, “The Affordances of Social Media Platforms,” in The SAGE Handbook of Social Media (London: SAGE Publications, 2018), 245, https://www.annehelmond.nl/2016/08/01/the-affordances-of-social-media-platforms/.

[4] Bucher and Helmond, “The Affordances of Social Media Platforms,” 245;

Neil Postman, “The Humanism of Media Ecology,” in Proceedings of the Media Ecology Association, vol. 1 (First Annual Convention, New York, NY, 2000), 10, https://media-ecology.org/resources/Documents/Proceedings/v1/v1-02-Postman.pdf.

[5] W. Lance Bennett and Alexandra Segerberg, “The Logic Of Connective Action: Digital Media and the Personalization of Contentious Politics,” Information, Communication & Society 15, no. 5 (2012): 748–54, https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2012.670661.

[6] Bennett and Segerberg, “The Logic Of Connective Action,” 748–54;

Ariadne Vromen, Michael A. Xenos, and Brian Loader, “Young People, Social Media and Connective Action: From Organisational Maintenance to Everyday Political Talk,” Journal of Youth Studies 18, no. 1 (2015): 82, https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2014.933198.

[7] Bucher and Helmond, “The Affordances of Social Media Platforms,” 243.

[8] Jenny L. Davis and James B. Chouinard, “Theorizing Affordances: From Request to Refuse,” Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society 36, no. 4 (2016): 244–46, https://doi.org/10.1177/0270467617714944.

[9] Medina Serrano, Papakyriakopoulos, and Hegelich, “Dancing to the Partisan Beat,” 257.

[10] Medina Serrano, Papakyriakopoulos, and Hegelich, 258;

Julia Chan, “Top Apps Worldwide for September 2020 by Downloads,” Sensor Tower Blog, accessed October 16, 2020,https://sensortower.com/blog/top-apps-worldwide-september-2020-by-downloads.

[11] Sarah Perez, “It’s Time to Pay Serious Attention to TikTok,” Tech Crunch, January 30, 2019, https://techcrunch.com/2019/01/29/its-time-to-pay-serious-attention-to-tiktok/.

[12] Medina Serrano, Papakyriakopoulos, and Hegelich, “Dancing to the Partisan Beat,” 264.

[13] “About TikTok | Our Mission,” TikTok, accessed October 16, 2020, https://www.tiktok.com/about?lang=en.

[14] Medina Serrano, Papakyriakopoulos, and Hegelich, “Dancing to the Partisan Beat,” 257.

[15] Vromen, Xenos, and Loader, “Young People, Social Media and Connective Action,” 82.

[16] Vromen, Xenos, and Loader, 82.

[17] Medina Serrano, Papakyriakopoulos, and Hegelich, “Dancing to the Partisan Beat,” 262;

John Herrman, “TikTok Is Shaping Politics. But How?,” The New York Times, June 28, 2020,https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/28/style/tiktok-teen-politics-gen-z.html.

[18] Medina Serrano, Papakyriakopoulos, and Hegelich, “Dancing to the Partisan Beat,” 264.

[19] Medina Serrano, Papakyriakopoulos, and Hegelich, 264.

[20] Siddharth Venkataramakrishnan, “TikTok Becomes Political Platform Ahead of US Election,” Financial Times, June 2, 2020,https://www.ft.com/content/c4c09793-993e-4ffd-9e46-2c609f98b79d.

[21] Light, Burgess, and Duguay, “The Walkthrough Method,” 881–900;

Machin and Mayr, How to Do Critical Discourse Analysis.

[22] Light, Burgess, and Duguay, “The Walkthrough Method,” 889-91.

[23] Machin and Mayr, How to Do Critical Discourse Analysis, 6-10.

[24] Light, Burgess, and Duguay, “The Walkthrough Method,” 889.

[25] TikTok, “About TikTok.”

[26] Light, Burgess, and Duguay, “The Walkthrough Method,” 889.

[27] Light, Burgess, and Duguay, 891.

[28] Light, Burgess, and Duguay, “The Walkthrough Method,” 891-92.

[29]Ioana Literat and Sarah van den Berg, “Buy Memes Low, Sell Memes High: Vernacular Criticism and Collective Negotiations of Value on Reddit’s MemeEconomy,” Information, Communication & Society 22, no. 2 (2019): 235,https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1366540.