23andMe: Visualizing Ancestries and Ethnic Identities in Neoliberal Society

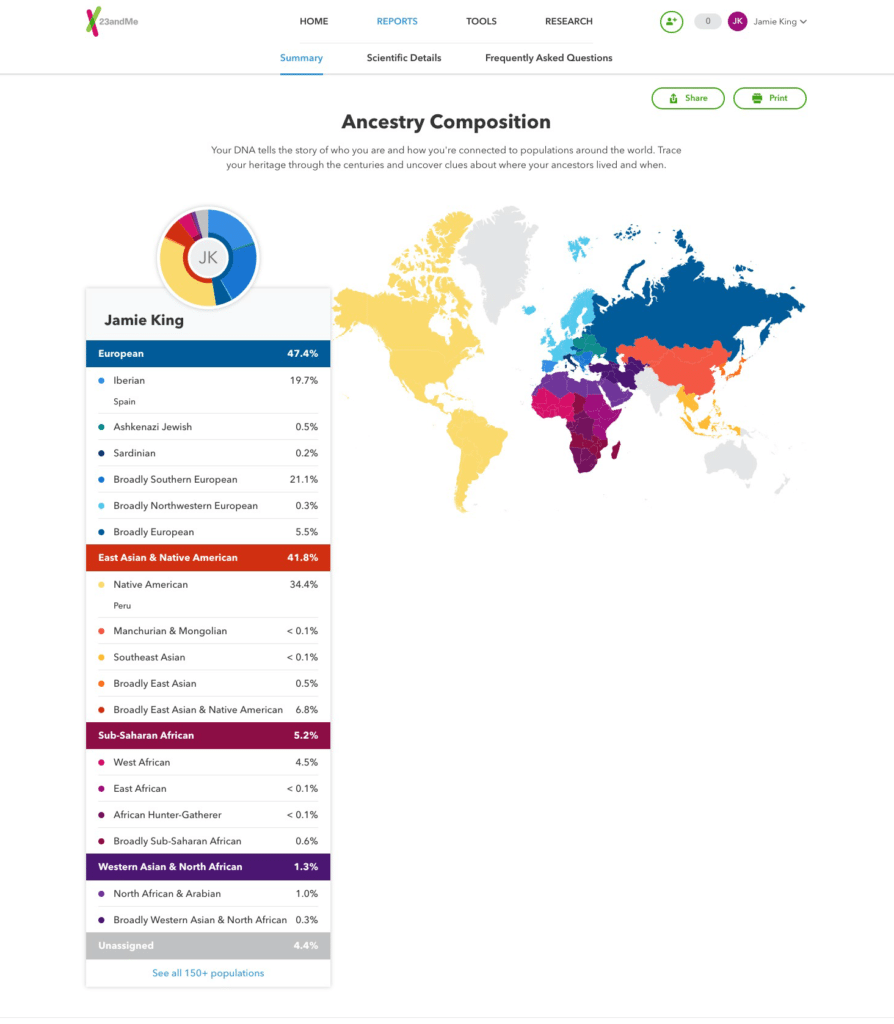

Our new media landscape is overwhelmed with data amidst a big data shift and the rise of data power, agency, advocacy, and pleasure within the context of neoliberal society. The endless amount of data is contributing to the growing pressure on researchers as well as media corporations to visualize data to better understand it and attempt to lift the veil of secrecy over big data. Visualizing our data is making it seemingly clearer and therefore almost tangible, which leads us to believe we are better understanding and absorbing information from media. To contextualize the relevance of data visualization within the new media realm I have chosen Kennedy and Hill’s journal article “The Pleasure and Pain of Visualizing Data in Times of Data Power” (2016), which describes the desire to visualize revolves around the contexts of data visualization, the ideological impact of visualizations, the politics of data power and neoliberalism, and visualization pleasures (Kennedy and Hill 2016, 1). Through my chosen new media object, DNA testing platform 23andMe, I will discuss the relationship between data visualizations and sociocultural and ethnic identities to explore the question of what are the implications of online genealogical ancestry platforms redefining our sense of identity through visualized representations of genetic (DNA) data?

Kennedy and Hill (2016) highlight the growing urge to visualize data is in our “increasingly datafied times” and “the anxieties that this produces” (2) which ultimately are products of two phenomena, datafication and neoliberalism (6). Datafication or to “datafy” is defined as putting information in a quantified format so it can be processed, organized and ultimately analyzed (6) often for financial gain of data companies and at the expense of users. Neoliberalism can be defined as a political and economic ideology that is directly linked to capitalism and encourages individualization of economic aspects of society and the obsession with self-improvement and technological development and its subsequent anxieties and insecurities (7). These phenomena contribute to the concept of data power which relies on the prevalence of numbers, data, and modern measurable forms of information which govern contemporary society (Kennedy and Hill 2016, 7-8). However, data is never free of bias, therefore data visualizations are not neutral representations of data similarly to how media technologies are not inherently neutral but rather mutable mediators and actors (5).

23andMe, founded in 2006, initially started as a personal genome service that provided customers access to their own genetic data to manage their health (Van Dijck and Poell 2016; Copeland 2020). It soon developed into the genealogical testing service it is today, but faced issues with the composition of users’ genealogical breakdowns being far too simple. With this, there were concerns over the service perpetuating ideas of inherent biological racial differences (Copeland 2020). Racism has been based on false science before and these genealogical breakdowns can pose a slippery slope if not properly represented and contextualized (Curtis 2019).

Although well established in its biological and scientific aspects, DNA testing and specifically my new media object 23andMe and its recognizable data visualizations have contributed to the mainstream prevalence of DNA testing services—now turned DNA platforms. 23andMe and similar DNA platforms have grown to act as data banks for both users and the platforms themselves. Van Dijck and Poell’s notion of double-edged logic describes the relationship between users and health platforms which promises users personal solutions whilst contributing to the greater good of scientific research, but on the other hand serves the interests of data companies for economic gain (2016, 1-2).

With society’s continued fascination with ethnic identities and the visualization of data, 23andMe and similar DNA platforms have gained more popularity in recent years. The issue that arises from visualizations and datafied representations is that DNA does not define culture and 23andMe reduce information to visualize data (Manovich 2011; Copeland 2020; Curtis 2019). Manovich (2011) explains reduction as one of the key principles of visualization as visualization is defined by the need to include or make visible. Data is thus created and ultimately influenced in the process of visualization (41). However, with the ever-growing amount of data, 23andMe with over 30 million users (Copeland 2020), there will continue to be a demand for visualized data to attempt to understand data and present it to the world. Additionally, as Kennedy and Hill argue our pleasure and the perceived good of data visualizations drive big data structures and give data a new power and agency (2016, 10).

Visualized DNA data brings previously unknown information to the surface. However, the nuances of racial and ethnic identities cannot be represented by such simple means as data visualizations do not equate to reality. How a 23andMe DNA test can “reveal” a person is only a certain percentage of their ethnicity does not take away the tangible visual identity of an individual or how they identify. As authoritative as data can be, seeing is believing, in the real world people are not discriminated against merely based on their genealogical profile but on what appears to the blind eye. As Copeland (2020) argues genetic information and thinking about these data often goes hand in hand with racist thoughts or tendencies. We must be critical of these data because like media and technology, data visualizations are not neutral presentations of data, but rather representations that may act as political or social vehicles of power and exert their affordances to privilege certain views, perpetuate existing power dynamics or forge new ones (Kennedy and Hill 2016, 5). Issues with data mining and new digital forms of discrimination, exclusion, invasion, monetization, exploitation, and privacy concerns can arise from data visualization and lack of transparency (Kennedy and Hill 2016, 7; Van Dijck and Poell 2016). Transparency is crucial in understanding data visualizations as often flawed reinterpretations and (re)presentations of data.

New media platforms are having to adapt to the rise of visualization and the role of aesthetics in directing media. Companies like 23andMe are redefining the relationship between the data, media, and identity. Our understanding of identity and especially ethnic identity is being shaped by relatively simple representations of often complex genetic histories which may be distorting our understanding of these identities and the significance of individual genealogical histories. This goes to show the ideological potential of data visualizations in sociocultural and political contexts and their role in new forms of governance and control (Kennedy and Hill 2016, 5) and forming new relationships and assemblages of information within neoliberal society (6).

References

Copeland, Libby. 2020. “Does a Pie Chart Change Who You Are?” Slate, July 16, 2020. https://slate.com/technology/2020/07/dna-test-ancestry-results-identity.html.

Curtis, Caitlin. 2019. “How DNA ancestry testing can change our ideas of who we are.” The Conversation, March 31, 2019. https://theconversation.com/how-dna-ancestry-testing-can-change-our-ideas-of-who-we-are-114428.

Manovich, Lev. 2011. ‘What is visualisation?’ Visual Studies, 26(1): 36–49.

Kennedy, Helen, and Rosemary Lucy Hill. 2016. “The Pleasure and Pain of Visualizing Data in Times of Data Power.” Television & New Media 18, no. 8: 769–782.

Van Dijck, José, and Thomas Poell. 2016. “Understanding the Promises and Premises of Online Health Platforms.” Big Data & Society 3, no. 1: 1–11.