“hello literally everyone”: A Case Study on Social Response to Facebook’s Infrastructure Disruption

A submission by Shiyi (Annie) Zhou, Zarah Noorani, Niels Willemsen and Ayoub Samadi

Facebook, now a common name in communication all over the world, faced a complete shutdown of services on October 4, 2021. This outage reflected on the entire “Facebook Family” of applications, including Instagram, Messenger, Whatsapp, Mapillary and Oculus. The shutdown lasted for about six to seven hours and effectively cut down the use of what we now consider essential modes of communication. This ordeal brought about a wave of domino effects, whether it was a hit on small businesses, Facebook’s stock price, or just a complete stop to virtual communication for many. Moreover, the infrastructural fallout affected not only the end-product consumers of the media outlet and its branches, but also the employees and producers at the company. It was reported that even Facebook employees had trouble accessing the mainframe systems at the main offices of Facebook, and weren’t able to enter the premises or even make calls on company issued phones.

News outlets and users were quick to address the issue through their respective channels with the latter taking to Twitter to express their frustration or opinion on the matter. While the reaction to the event was, for the most part, lighthearted with users posting memes and poking fun at the whole event, it seems that some impactful consequences arose as a result of the outage (Jiménez and Patel). In particular, users were made more aware of the underlying systems that kept Facebook functioning. This infrastructure is invisible, as its designers purposely obfuscate its presence from the overall user experience (Bowker and Star 230). In the particular case of the Facebook outage, the material infrastructure that facilitates data flow and keeps the platform working was compromised. In such cases, the infrastructure renders itself visible and vulnerable to analysis and criticism (Bowker and Star, 231).

As such, the case study of the Facebook outage is an interesting one, because the infrastructure was made materially visible to users on a massive scale. We take from the definition for infrastructure as proposed by Bowker and Star, taking into account its flexibility to respond to outside forces, its embeddedness within socio political and economic spheres, and the implementation of the aforementioned forces into its technical design and execution (231, 232). This paper therefore takes this incident as its case study by 1) gauging the general sentiment towards Facebook and its platforms and 2) determining the potential for such infrastructural malfunctions to make way for critical introspection.

With Facebook’s own discourse made so vulnerable during this event, individual users were handed an opportunity to position themselves in a way that allowed them to criticize the platform as well as their own habits. Such an opportunity is rare and we believe that the potential this carries is wide and far-reaching. A collective awareness of the infrastructural makeup of Facebook is powerful insofar as it allows for critical intervention on a global scale, challenging the hegemonic discourse and allowing for alternative opinions on Facebook’s management and accepted cultural practices to be heard. Casual users and social media professionals were united in their shared incapacity to access their desired data. This paper will explore these effects by amalgamating a general impression of the public opinion through news media coverage and tweet content.

Methodologies

As mentioned, we have decided to use Twitter, because apart from Facebook and the platforms they own, it is one of the largest social networking sites. Also, Twitter was “flooded with users”, as a result of the Facebook outage (Timsit and Mateus). Through looking at news outlet’s response to the outage, we try to build an argument about the implication that the media makes about Facebook following the outage, as well as the current disposition concerning Facebook in general, and how this is reflected through this infrastructure disruption

After, based on this movement from Facebook’s platforms to Twitter, we hypothesise that an audience of reflective users that mention the effect of the Facebook outage in their tweets as well as engagement behavior (specifically retweets). Consequently, we will look at the top tweets that are most engaged with (retweeted) mentioning the #facebookdown tag during the outage, since this most accurately represents the disposition of the users concerned with the Facebook outage during that time. Though it would be interesting to compare the tweets before, during and after the outage, our main goal is to look into the direct social response to the disruption of a global online infrastructure.

Additionally, we decided to use discourse analysis for the tweets that mention the #facebookdown, a method that has been used in similar studies (Cravens et al. 374; Dambo et al. 6). Even though hashtags based on breaking events might not have settled (Bruns and Burgess, 5), the Twitter community was quick to develop an ad hoc public surrounding the event, going beyond the “follower” networks. We are considering the fact that not all tweets about the outage contain the hashtag, but we are confident that all posts with the hashtag concern the outage, meaning our corpus is focused, efficient and to an extent representative.

Using Twitter’s built-in advanced search method, we found our corpus of tweets by looking for items containing the #facebookdown tag with at least 500 retweets, that were posted between Sunday to Tuesday, October 3 and October 5, 2021 since the outage took place on Monday October 4. Unfortunately, Twitter does not allow it’s users to sort the tweets they looked for by date or popularity, meaning it is sorted by their algorithms, causing a potential lack in representability in the order of the tweets that are shown. However since the amount of tweets is relatively small, this should not matter for our research. Through trial and error, we found that a minimum of 500 retweets strike a good balance between publicity and volume of tweets that were shown.

In order to ensure the privacy of the users posting the tweets we are analyzing, we will not be disclosing any information that could identify the users. Though all tweets analyzed are public, we try our best to ensure the privacy of all non-public figures posting with this hashtag. Following Boyd and Crawford‘s principle (672), it is not ethical to collect just because it is accessible.

News Coverage

Much of the general sentiment towards the event can be felt by looking at the media coverage by news platforms during this time. Major outlets capitalized on the opportunity to not only cover the most trending story of the day but also to make use of the situation’s potential to spark political conversation. In a New York Times op-ed, attention was taken towards Facebook’s infrastructural design, criticizing its ethical validity and overall direction (Bokat-Lindell). For instance, the article mentions how the platform’s algorithmic infrastructure prioritizes user action that is conducive to benefiting the company’s profit with callous disregard to the user’s wellbeing. In an interview with CBS, former Facebook employee and whistleblower Frances Haugen stated: “The thing I saw at Facebook over and over again was there were conflicts of interest between what was good for the public and what was good for Facebook. And Facebook, over and over again, chose to optimize for its own interests, like making more money” (Pelley). While this statement was given independent of the outage that took place, it seems that the outage proved to be the perfect opportunity to highlight and make these types of opinions heard.

This is in reference to the company’s approach to their platforms’ infrastructure. It would seem that despite the flexibility that infrastructures afford, Facebook chooses to prioritize functionalities which increase user engagement so as to maximize the profitability and value of the platforms’ ad space. In Facebook’s quarter-by-quarter breakdown of their revenue from the 2020 calendar year, it was estimated that a grand total of 84-billion dollars was made from the platforms’ advertising (Facebook). Naturally, with advertising the largest source of income, much of the company’s effort targets user engagement and attention.

As such, much of the design that is incorporated into the platform is targeted towards this objective. The algorithmic infrastructure which filters content based on personal interest does much for this enterprise. An expansive body of research has been dedicated to the negative impacts of such an infrastructure on user well-being (e.g. Chatzopoulou et al. 1289). Moreover, infrastructure standardizes interactivity and by extension user experience and habit (Bowker and Star 234). Instagram’s and Facebook’s algorithm depend heavily on “Likes” as a quantitative tool of gauging interest and keeping track of information flow. Research done on this infrastructural element shows the harm it has on user wellbeing, in particular to affect and loneliness by quantifying popularity and social acceptance (Wallace and Buil, 4). As a result, users might feel alienated or not accepted by the response that they receive.

Such issues clearly derive from the platform’s infrastructural backbone. The Facebook outage undermined the invisibility of these infrastructures and helped foster a critical discourse. Not only were casual users’ habits interrupted, but social media managers, ‘influencers’ and professionals who depended on the platform for their livelihood had to put their projects on halt. During this time, much debate arose surrounding Facebook’s infrastructure and questions were brought up as to current practices associated with social media and their psychological effect on its users. Due to the infrastructure’s malfunction, it rendered itself visible, thereby making Facebook vulnerable to criticism. While the major news outlets used this opportunity to make existing concerns heard, individual users took to Twitter to voice their own opinions and personal experiences. Using discourse analysis, we decided to look at whether the opinions shared by the news outlets were also reflected in the general discourse of the event.

Discourse analysis

Due of the significant number of people that Facebook and its owned services reach, many people quickly noted its outage and proceeded to discuss it on other platforms, which represents a kind of collective awareness of the infrastructural disruption. Serving as one of the major means of communication, Twitter was then under the spotlight, where they said “hello” to “literally everyone” (Figure 1). The current situation brought users to the same platform, which potentially caused more convenience in communication, but also revealed their problematic heavy reliance on so many apps from the world’s largest social media company at the same time.

Hence, we selected some of the most retweeted tweets and search with the hashtag #facebookdown between October 3 to October 5 to figure out the most related and time-effective posts. Through this, we try to understand how the users behind those tweets roughly think about and joke about the outage. We did this through discourse analysis of those tweets including the hashtag #facebookdown.

Each individual has very different angles and concerns about the breakdown. We simply analyze posts from two categories: users and public figures or companies to better understand their attitudes and how they view the problem from different perspectives.

Users across the platform were generally playful with memes about Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApps icons (Figure 2). The theme of most posts is funny and joyful, engaging in banter and generally lightening the mood of the public. Jokes and venting ensue during the event. Some even teased those who work in social media with GIFs of busy electricians, who seem to have no ideas to deal with technical problems. Moreover, one played jokes on Netflix’s new hit show Squid Game (Figure 3), showcasing that Facebook and its family of apps (contestants) are hit by Twitter (the machine doll). Furthermore, in the same series, the broken pieces represent the losers, and only Twitter’s logo is intact (the winner) (Figure 4).

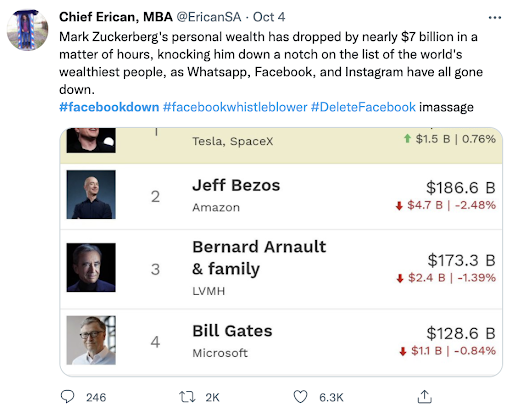

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg appeared to be in the center of the event and from the public view. His personal wealth dropped by nearly $7 billion in a matter of hours since shutdown and became the 5th richest man in the world, said by social entrepreneur Chief Erican @EricanSA on Twitter (Figure 5). Many social media users also posted pictures of ‘Zuckerberg’ getting tangled in the wires (Figure 6).

Facebook’s outage soon makes everyone online and be more concentrated without some apps’ distraction. In this way, some of the big companies, organizations, and brands thought it was a great opportunity to market their products and services via Twitter. Several company’s official accounts quickly tweeted to check in with their customers and even run Twitter’s giveaways to increase the engagement, such as entering a prize draw or posting a new release. Chasing after the hot trend, WHO also posted that, “Never let your masks down” to catch attention (Figure 7). Meanwhile, politicians like Josh Shapiro (@JoshShapiroPA), the attorney general of Pennsylvania, used for political purposes, called for actions by saying in a tweet that, “Now that you’re all here, I want to take this opportunity to say: Raise the minimum wage. Defend the right to vote. Protect abortion access.”

The shutdown had sparked heated discussions and divisive conversations on specific causes of this issue among professionals and social media users. The company did not disclose the cause of the outage. Six hours later, they attributed the downtime to a “server configuration change.”

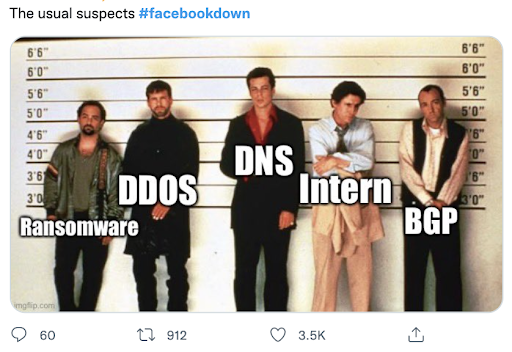

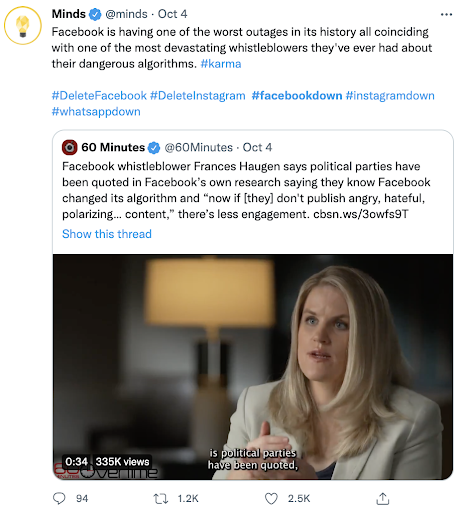

Computer experts and professionals made thoughtful assumptions and offered possible solutions. Before the outage, Facebook has already experienced heavy criticism. One of its main and most famous critics, Edward Snowden (@Snowden), the president at Freedom of Press and a former computer intelligence consultant, tweeted that: “Facebook and Instagram go mysteriously offline and, for one shining day, the world becomes a healthier place.” “You and your friends should probably be using a more private, non-profit alternative like @Signalapp anyway (or another open-source app of your choice). It’s just as free, and takes like 30 seconds to switch,” he added. Also, the Domain Name System (DNS) and DDoS attacks on providers or servers are most likely to be interpreted as the symptom of hours-long inaccessibility of Facebook and its owned platforms (Figure 10). For instance, Minds (@minds) retweeted 60 Minutes’ (@60Mintes) post to relate the issue to the company whistleblower (Figure 11).

Discussion & Conclusion

Following our analysis of the Facebook outage, it is clear that while this event lasted only for about 6 hours, it spread havoc over a variety of fields. An event of this magnitude shook the functioning of the tools of new media and communication to such an extent that it barred users from even logging on. As mentioned earlier, it was rather interesting to speculate over the concerned infrastructure and upon analysing it closely in this essay, we can safely say that there were significant effects reflective in the functioning of the platform.

Firstly, we delved into coverage by news outlets such as the New York Times and CBS News to analyse the reflection of an event this significant on journalism and general reportage. The news coverage showed a critical reflection the Facebook algorithm, both through items that discussed the outage itself, as well as coverage critical of our dependence on the concerned infrastructure itself.

Given the nature of our research, we were able to find user-generated data from Twitter, and were able to finally hypothesize not only that users visibly switched to an alternate platform but also their reception to the shift in media sites. It also stands relevant to Bowker and Star’s theory on Infrastructures as it breaks down the function of user experience on a media platform and habit. To conclude, we can safely state that while the Facebook outage struck out as a haptic break for several users and businesses (including Facebook itself), it also proved to be an outlet for users to post their opinions on an alternate media site and uncovered the infrastructural makeup of our usage habits.

Though we got a general impression of the response to the Facebook outage, our tools of collecting the data were limited, given that we were not granted access to the Academic Twitter API. This meant that we could not collect actual data from Twitter, and we had to use the ‘advanced search’ provided in the general user interface of Twitter. This caused the tweets to be sorted algorithmically by twitter, jeopardizing the representability of the content we analyzed. Also, because we had to use this method, we could not sort by time, which would have helped in analyzing the disposition of users as the outage progressed. These are all issues that could be resolved in future work.

Word count: 2744

Bibliography

Bokat-Lindell, Spencer. “Opinion | Facebook Was down for a Few Hours. Should It Go Away Forever?” The New York Times, 5 Oct. 2021, www.nytimes.com/2021/10/05/opinion/facebook-whatsapp-instagram.html.

Bruns, Axel, and Jean Burgess. “The Use of Twitter Hashtags in the Formation of Ad Hoc Publics.” Proceedings of the 6th European Consortium for Political Research (ECPR) General Conference 2011, The European Consortium for Political Research (ECPR), 2011, pp. 1–9.

Chatzopoulou, Elena, et al. “Instagram and Body Image: Motivation to Conform to the ‘Instabod’ and Consequences on Young Male Wellbeing.” Journal of Consumer Affairs, vol. 54, no. 4, Sept. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12329.

Cravens, Jaclyn D., et al. “Why I Stayed/Left: An Analysis of Voices of Intimate Partner Violence on Social Media.” Contemporary Family Therapy, vol. 37, no. 4, Springer, 2015, pp. 372–85.

Dambo, Tamar Haruna, et al. “Office of the Citizen: A Qualitative Analysis of Twitter Activity during the Lekki Shooting in Nigeria’s# EndSARS Protests.” Information, Communication & Society, Taylor & Francis, 2021, pp. 1–18.

Facebook. “Facebook Reports Fourth Quarter and Full Year 2020 Results.” Investor.fb.com, 27 Jan. 2021, https://investor.fb.com/investor-news/press-release-details/2021/Facebook-Reports-Fourth-Quarter-and-Full-Year-2020-Results/default.aspx

Jiménez, Jesus, and Vimal Patel. “Users Turn to Twitter after Facebook Outage. Jokes and Venting Ensue.” The New York Times, 4 Oct. 2021, www.nytimes.com/live/2021/10/04/business/news-business-stock-market.

Pelley, Scott. “Whistleblower: Facebook Is Misleading the Public on Progress against Hate Speech, Violence, Misinformation.” Www.cbsnews.com, 4 Oct. 2021, www.cbsnews.com/news/facebook-whistleblower-frances-haugen-misinformation-public-60-minutes-2021-10-03/.

Star, Susan Leigh, and Geoffrey C. Bowker. “How to Infrastructure.” Handbook of New Media: Social Shaping and Social Consequences of ICTs, edited by Leah A. Lievrouw and Sonia Livingstone, SAGE Publications Ltd., 2002, pp. 230–45.

Wallace, Elaine, and Isabel Buil. “Hiding Instagram Likes: Effects on Negative Affect and Loneliness.” Personality and Individual Differences, Nov. 2020, p. 110509, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110509.

Timsit, Annabelle, and Sofia Diogo Mateus. “‘Hello Literally Everyone’: Twitter Flooded with Users during Facebook, Instagram Outage.” Washington Post, 2021. www.washingtonpost.com, https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2021/10/05/twitter-users-facebook-outage-instagram-whatsapp/.

Twitter Posts and Figures. Retrieved by Oct. 29, 2021. https://twitter.com/search?q=(%23facebookdown)%20min_retweets%3A500%20until%3A2021-10-05%20since%3A2021-10-03&src=typed_query&f=top