Moving Money: A Comparative Infrastructural Analysis and the Impact of Trust

Abtract

By making infrastructure visible, we are able to see clearly how it shapes our environment and our experiences of it. This paper examines how policies and regulations, just as much as the technical backbone of payment applications, act as infrastructure that mediates platform affordances in different socioeconomic contexts. We also see clearly how these infrastructure can differ from one context to another, as well as how the platforms’ relationships with infrastructure shape their impact on socioeconomic outcomes.

Context

While 94.6% of American households have a bank account in 2019 (Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), 2020), 45% of Nigerian adults have a bank account in 2020 (EFInA, 2020) largely because their incomes are irregular or bank branches are too far from them. Indeed, Nigerian banks only have an estimated 4,644 branches to serve 108 million adults in a country(Idris, 2021) with largely poor road networks and transport infrastructure. Even accounting for gaps in digital literacy, the differences in these two economies mean that technical solutions seeking to facilitate faster and more efficient payments for businesses that operate in these different environments have vastly different needs.

Digital payment companies have existed for years in the US and the EU, but the payments industry in Nigeria is fairly new. The oldest player in the market Paga has only been in existence since 2012, while one of the oldest digital payment companies from the United States Paypal has been around since 1998. The industry in Nigeria has been growing steadily, and saw a huge boost in usage during the COVID-19 pandemic, with an increase in the volume of mobile payments topping 7.4 million transactions in January 2020, up from just 724,803 in January 2019 (NIBSS, 2021).

Payment applications like Stripe and others like Square, Paypal and even newer operators like AmazonPay and ApplePay tend to have a clear approach to the way they operate; they facilitate payments between merchants and vendors, and allow users to generate and/or receive payments and invoices. Payment companies in African countries often do not stop at business-to-business service. MPesa uses SMS and internet-enabled platforms to become an alternative to using a bank card in Kenya; Cellulant in Ghana teamed up with telecommunications entity MTN to expand its digital payments services to paying utilities; Paystack created a digital marketplace where people could create digital storefronts to sell directly.

Most research on electronic payments in Nigeria and other African countries focuses on the socioeconomic and developmental impact of the remittances on the local economy, but does not quite examine what shapes the socio-technical systems that undergird these technologies, or the impact these have on how payment companies work to meet the needs of their intended users. This paper seeks to do just that.

Methodology

For a comparative analysis, The Chinese-funded OPay is the Nigeria-based example, because it currently dominates the mobile payments business in Nigeria, accounting for 60% or ₦102.4 billion — ~160 million euros today — of the total value of transactions in April 2021 which was ₦172.1 billion (Idris, 2021). Stripe is the U.S.-based example, because it is one of the newer and more successful payment companies in the United States, working with companies such as Amazon and Facebook (Armstrong, 2018).

That said, these two companies are largely typical of payment companies in their different countries. This paper will begin with an introduction into the mobile payments, situate these platforms in the infrastructure/platform dichotomy introduced by Plantin et al, and use Star and Bowker’s definition of infrastructure as the basis of a comparative infrastructural analysis that does two things: explains how the policy and environment determines the technical infrastructure, and how this infrastructure drives the platforms’ affordances and constraints.

Defining mobile payments

Payment applications are those that create non-banking platforms that handle payments and facilitate the purchase of goods and services. These apps are not to be confused with banks, which are financial institutions that receive deposits and make loans. Banks could create payment platforms of their own. Payment services would need to have banking licenses to disburse loans, although they can hold funds (typically in a “wallet” feature) sent to the user’s account from any bank.

Although payment companies typically work the same way to facilitate payments, the modes of production and differences in economies give rise to material differences in the look-and-feel of these apps, as well as the functionalities of their platforms. This is not to say that apps cannot be used in different contexts; after all, Stripe, Square and PayPal operate in multiple countries across the EU, North America and Asia quite comfortably. However, their use cases can change depending on the different environments it is used in. If these apps were to be set up in Nigeria with the ambition to be a company in the payment space, they too would change their strategy to fit the context.

Payment applications – Platform or Infrastructure?

Payment companies blur the line between platforms and infrastructure. You can call payment companies platforms because they provide technological frameworks on which others can build on, and afford multi-sided relationships between merchants and buyers, or indeed any groups of people who need to facilitate a transaction (Plantin et al., 2016). Like other platforms, their exhibit three dimensions of platformization: The datafication is driven by complementors integrating platform data into products and services; they create multi-sided markets, affecting distributions of wealth; their governance of the platform structures how users interact through contracts and policies, and how and what users can do on the platform.

Although these applications are platforms, they do share some characteristics of infrastructure. This is due to their embeddedness, as these apps allow for integration with other apps as well as other businesses’ other practices. Indeed, by sharing their API libraries, they facilitate access to their platform in such a way that — at their most successful — they attain such ubiquity that they become a part of other businesses’ conventions and their existence is taken for granted, much like Google. The most successful of these businesses also have reach to do more than just facilitate payments; in addition to allowing registered companies and individuals to accept payments, they also allow users to send and receive invoices, handle and pay subscriptions, manage online stores, and manage payroll needs.

Although they are more appropriately considered to be platforms, it is worth keeping in mind that the aim for payment applications is to attain the ubiquity of infrastructure.

An Infrastructural Analysis of Stripe and OPay

An infrastructural analysis refers to the study of essential socio-technical systems that undergird platforms. The term infrastructure is hard to define, and often depends on who is using it, but for the purposes of this paper we use the definition of that which is between things, mediated by the tools (Star & Bowker, 2006). Policies are infrastructure because they help define standards of the operating environment in a more regimented way than more unspoken things like social trust do. The technical aspects of the payment systems are infrastructure because of their embeddedness into the operations of the applications and the way they invisibly support tasks carried out on the platforms. Each of these infrastructural aspects of the platforms shape the platforms’ affordances in many ways.

Differences in the Policy and Regulatory Environment

The United States has no national policy or regulatory body managing activities of fintech companies. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) enforces consumer protection laws and anti-discrimination laws on the activities on these companies. Individual states in the United States have more control over their individual monetary and fiscal policies, so payment companies have had to engage individual states for licensing. This means that when Stripe was setting up they had to engage with individual states separately to align their practices in compliance with each of the country’s 50 state’s regulations before being able to facilitate transactions interstate. It was only in late 2020 that the Conference of State Bank Supervisors (CSBS) signed on to a multi-state money services business licensing agreement (Reena Agrawal Sahni, 2021) to make it easier for inter-state money transmitting processes. Stripe still has some services that vary slightly from one American state to another, and the way different issues are resolved can change from state to state (Stripe Payments Company Licenses | Stripe).

By contrast, Nigeria’s government is more centralised in its handling of monetary policy and regulation of financial industry actors. When reports showed that 32% of the adult population had access to formal banking services in 2012, the Nigerian government through the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) instituted a National Financial Inclusion Strategy to improve access to banking services for the unbanked (Central Bank of Nigeria, 2018). This allowed for payment companies like OPay to enter the space.

The long-established banks who have a closer relationship with financial regulators largely see payment companies as a threat because of their ability to reach more ordinary Nigerians than they. This results in a push-and-pull whereby the apex bank’s policies are not always welcoming to new actors. In 2021, the government increased the barriers to entry for any further players in the market by stating that new payment providers have to hold N2 billion in capital requirements and escrow a refundable N2 billion with the Central Bank of Nigeria (“CBN Issues New Licence and Capital Requirements for FinTechs,” 2021). For example, licensed non-banking platforms have seen their accounts frozen by the apex bank without warning (Adegboyega & Abdulkareem Mojeed, 2021). Payment companies in Nigeria as a result have to have entire dedicated Government Relations departments who can engage directly with CBN officials formally and informally, and help them anticipate any potential regulatory headwinds that may be coming their way.

Differences in the infrastructure of payment systems

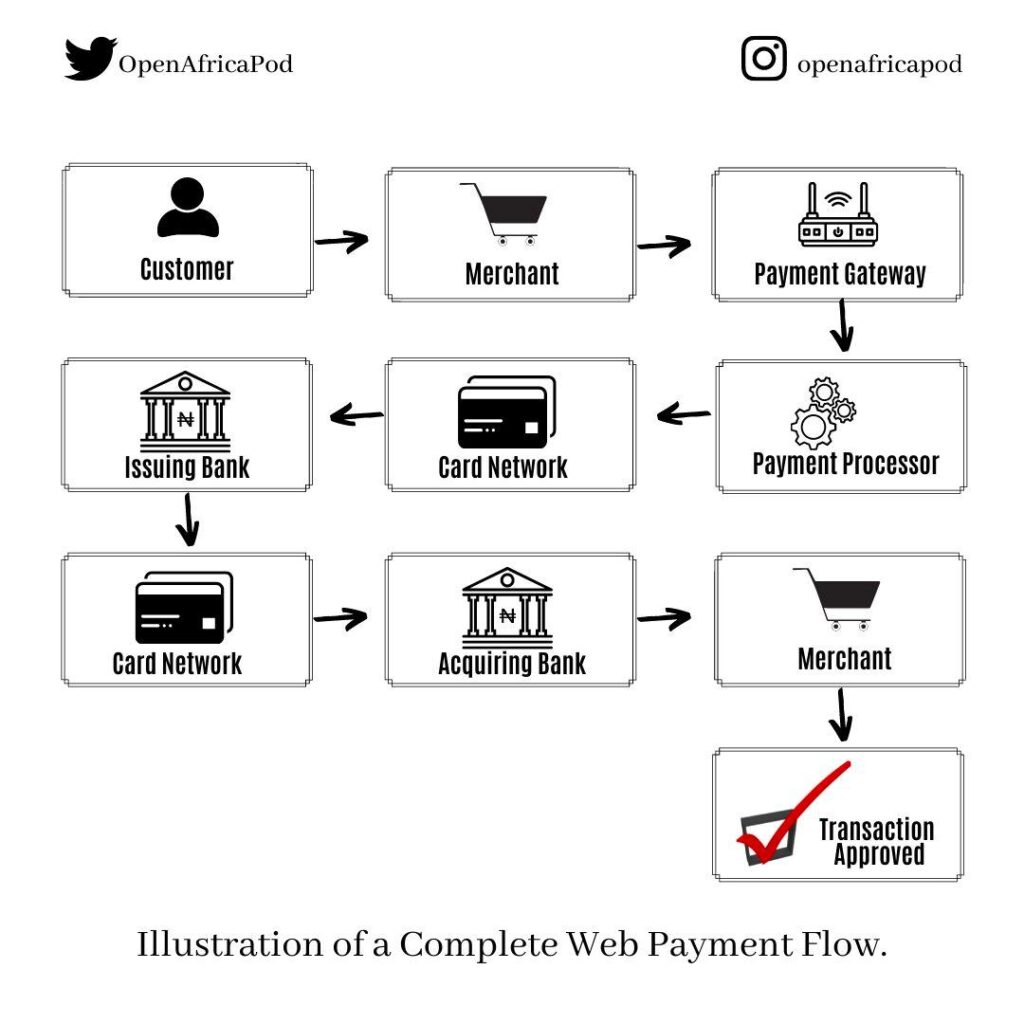

In the US, companies like Stripe have licenses that enable them to act as a middleman that manages the technical side of the cardholder information transfer, a payment processor, and a merchant account. These are the main elements, and each of these actors get some money from each transaction:

- Payment gateway – A middleman between the card companies and the payment processor. The payment gateway essentially manages the technical side of the cardholder information transfer, ensuring that the transaction is completed quickly and securely.

- Payment processor – A third-party that manages the card transaction process. The payment processor will communicate your customer’s card details with your bank and their own bank, and assuming that they have enough funds in the account, the payment will go through.

- Merchant account – A special kind of bank account that businesses use to accept credit/debit card payments. Without a merchant account, you won’t be able to accept these types of payments, which is why start-up businesses should register for an account as soon as possible.

The same elements hold in Nigeria, but with a different dynamic. Because Nigeria is a much more centralised system than the United States, there can also be a centralised regulation of the payment transfer space. The Nigerian Interbank Processing Systems (NIBSS) is a digital system created by the Central Bank of Nigeria that helps govern automated processing, fund transfer instructions and settlement of payments. This became necessary because of the lack of communication between banks. In the United States, with 95% of American households engaged in retail banking services, there is more of a direct benefit to them to work to make payments seamless for the average consumer.

As such, it is of benefit to both the issuing bank (making the payment) and the acquiring bank (receiving the payment) in the United States to work together and ensure that transactions fail less. Banks in Nigeria do not make the majority of their money from retail banking services like loans and access to credit, as much as they do from the deposits of high net worth individuals and entities, assets management and foreign currency trading. As such, there is less collaboration between banks to facilitate easier transactions. Payment companies help negotiate that gap in Nigeria, but banks in Nigeria have less interest in fixing issues systematically than in the United States.

In Nigeria, the system works thus: the payment company sends a message to the bank that owns the card, checks if the person has money and if the card is valid and can be debited, the bank sends a message to allow the cards to be debited. The gateway then sends to the payment processor, who has the engagement with your bank and card network separately. These companies will then communicate to the issuing bank to confirm the transaction back to the card network, who then return the message of the transaction to the bank where the funds are to be directed. All of this has to happen before the funds can be transferred to the merchant’s bank account, and each of these actors — the originating bank, the issuing bank, the card networks, gateway and service provider — all receive some money as commission.

As such, rather than a simple three-step approach to payments as you would find in the United States, in Nigeria it looks like this:

Between unreliable internet connectivity and the fact that payments have to go through so many different actors, Nigerian payment companies have a much higher rate of failed transactions than those in the United States. Data on mobile money transfer failures are hard to find, but they use much the same gateways and processing as a standard POS transaction and the failure rate for those can be as high as 23% in a day (Ogunfuwa, 2020). It also means that Nigerian payment processing companies and payment gateway providers can feasibly claim enormous transaction volumes when seeking foreign investment, even if they do not make clear how many of those transactions are merely because of a repeat of failed ones.

The Impact of Societal Trust on platforms

The United States is a higher trust society than Nigeria, and Americans are likely to be documented in their public system through such things as Social Security, State Identification and Driver’s Licenses. These are important because they make it much easier for financial system actors to identify their customers in larger public databases. The banking system in the United States is quite well developed, with 95% of American households having bank accounts and largely trusting the banks to keep their money. Card companies like Mastercard and Visa also have head offices in the country, too.

Also, because of Social Security and the ease with which people can get Driver’s Licenses, the Know Your Customer (KYC) requirements are fairly easy to meet for customers of payment companies like Stripe. As the banks are quite effective in reaching the country’s vast population (Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, 2020), there is a fair amount of financial literacy on how financial instruments work and companies like Stripe can focus on delivering payment systems and not have to worry about other services. Furthermore, Anti-Money Laundering (AML) regulation caps the amount of money that non-bank actors can keep in digital wallets, so even though Stripe does have an integration feature for all the digital wallets a user might have, it is still no real threat to a regular bank.

It is also because of the high level of societal trust that the Stripe platform affords less friction in the usage of its platform. With Stripe, one only needs to input their password once and is not required to do so again at any point. While money laundering and identity theft is a concern everywhere, Stripe, like other successful payment companies, is less fearful of regulators because they have easy access to capital from which they can afford to pay any fines or bear any costs if anything shoddy happens on their platform.

By contrast, KYC requirements are a huge burden on financial sector actors in Nigeria (Dike Onwuamaeze, 2021) because there is no one centralised national database on which financial sector actors can rely. These requirements are important to the Central Bank, because of the threat of money laundering and finance-related scams and how badly they have dented the country’s reputation internationally and deepen distrust in the system. Taken together with the fact that there are only over 4,600 bank branches serving an adult population of 106 million people, over half of whom live in rural areas and 40% of whom live in poverty, it is not viable for the banks to spend much more on opening many more branches to reach customers that cannot deposit all that much, while further driving up KYC-related costs. This state of affairs allowed the unbanked population to remain a largely untreated problem until the rise of mobile payments.

For many Nigerian businesses trying to access formal banking services, KYC requirements are often too stringent for their businesses to meet. 46% of Nigerian adults own a business of some sort, and 96% of those businesses hire fewer than 10 people, qualifying them as micro-enterprises (EFInA, 2020). Many of these microbusinesses are not formally registered or pay taxes. The formal sector is only 7% of the national economy. This means that companies like OPay — unlike its American counterparts — have to create a business model wherein they can: 1) make money from the largely unbanked population; 2) innovate around the KYC requirements to do so.

To innovate around the KYC requirements, OPay’s platform allows all users regardless of their identification to use the platform, but denies some levels of access to service depending on the kind of formal identification a user might have. For example: with the provision of a name and phone number, OPay allows you to deposit and transfer 50,000 naira into and out of your account. With the provision of a Central Bank-issued Bank Verification Number (BVN), that limit increases to 100,000 naira. With the provision of a passport or driver’s license, all limits are removed. Because of the aforementioned National Financial Inclusion Strategy by the Central Bank, payment companies in Nigeria have no AML-related limit. This allows for users to have as much money as they want in a non-bank payment provider’s digital wallet.

Also as part of deepening trust with more digitally literate users, the OPay platform allows users to do a lot of other non-banking related services, such as purchasing phone credit, or paying electricity, cable and internet bills. This follows the Google model of providing seemingly free or inexpensive add-on services to help build user reliance on their platform. In addition to the KYC-related workarounds, OPay’s platform demonstrates wariness of the level of trust in Nigerian society by introducing friction when trying to access different services on its platform. At every point, the user is asked to provide a password to further ensure the security of every transaction they might make.

The Agency Banking model and impact on data collection

Unlike Stripe, OPay cannot collect data on all the users of its platform because the latter has a large unbanked, digitally illiterate population to contend with. Data gathering is more effective on Opay users who can use the full complement of services by themselves, but OPay is also able to gather information on user spending and saving habits on users who are less digitally literate in more localized ways.

OPay is among payment companies leading the charge with the use of an agency banking model to innovate around the KYC requirements and meet the largely unbanked rural population. The agency banking model is an example of how infrastructure becomes visible upon breakdown (Star & Bowker, 2006), because the technical infrastructure fails to meet the needs of rural, unbanked, digitally-illiterate users, for whom the platform does not have affordances that fit their needs. With this agency banking model, a network of agents who live amongst the people in the rural, hard-to-reach areas. These agents can tell rural people how OPay’s system works in a language they can understand, helping them better be able to trust a web-based service since they can connect it to a face they recognize from their community. Instead of giving them an app to download, OPay agents give them unique SMS-generated short codes per transaction that enable these rural residents to transfer and receive money from agents anywhere in the country, and in cash.

The agency banking model also adds a unique aspect to the design of payment services technical platforms: each agent (or network Manager, as they are called) can log in to see how other agents are performing in their immediate vicinity in real-time. This sharing of information lets agents know if there are internet network failures in their immediate community, so they know whether or not to attempt to make transactions at a given time. Agents being able to share this kind of information with their community users also helps build trust.

Conclusion

Policy is a key factor in determining the shape of sociotechnical systems, and shapes the experience of users in numerous unseen ways. While this paper focused entirely on policies that determine monetary and fiscal policy instruments, there is an opportunity to determine what other forms of policy engagement undergird apps that shape our financial world, and even how these might affect our experiences with these apps depending on our age group, gender or class.

Bibliography

- Armstrong, S. (2018, October 5). The untold story of Stripe, the secretive $20bn startup driving Apple, Amazon and Facebook. Wired UK. https://www.wired.co.uk/article/stripe-payments-apple-amazon-facebook

- Dike Onwuamaeze. (2021, June 2). KPMG: Nigerian Banks Spend Billions Annually on KYCs. THISDAYLIVE. https://www.thisdaylive.com/index.php/2021/06/02/kpmg-nigerian-banks-spend-billions-annually-on-kycs/

- EFInA. (n.d.). Financial Inclusion. EFInA: Enhancing Financial Innovation and Access. Retrieved October 25, 2021, from https://efina.org.ng/about/financial-inclusion/

- Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). (2020). Household Use of Banking and Financial Services [Survey]. Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). https://www.fdic.gov/analysis/household-survey/2019report.pdf

- Idris, A. (2021, July 15). In Nigeria, where there’s a shop, there’s a bank. Rest of World. https://restofworld.org/2021/a-bank-at-every-corner-store-agency-banking-is-transforming-nigerian-business/

- NIBSS. (2021). NIBSS Insights—Instant Payments 2020 (No. 3). National Inter-Bank Service System (NIBSS). https://7a8d075c.flowpaper.com/NIBSSInsight3rdEdition1/

- Ogunfuwa, I. (2020, August 1). Eid-El Kabir: Errors push PoS failed payments to 23%. Punch Newspapers. https://punchng.com/eid-el-kabir-errors-push-pos-failed-payments-to-23/

- Plantin, J.-C., Christian Sandvig, Paul N Edwards, & Carl Lagoze. (2016). Infrastructure studies meet platform studies in the age of Google and Facebook. New Media and Society, 20(1), 293–310. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816661553

- Star, S. L., & Bowker, G. C. (2006). Handbook of New Media: Social Shaping and Social Consequences of ICTs (Updated Student Edition). SAGE Publications.

- Stripe Payments Company Licenses | Stripe. (n.d.). Retrieved October 29, 2021, from https://stripe.com/spc/licenses