Putting the “face” in Facebook: Examining the role of digital media mediation through Facebook’s latest smart glasses

In Reality Check Digital Methods, Venturini et al make the claim that, though we upload our own content to our social media profiles, digital media itself “belong[s] to the companies and institutions that have paid the huge cost necessary to set up their infrastructures” (Venturini et al 4197). This implies a clear delineation between the personal and, through engaging with a corporate entity, the commercial. How personal content becomes a commercial object depends on each digital media platform’s marketing strategy, one that is only visible depending on each company’s commitment to transparency, making them, the parties with the most to lose, “the gatekeepers of their traceability” (Venturini et al 4197). As internet literacy grows the phrase “if something is free, you’re the product” has entered the mainstream. However the line between the personal and the commercial blurs once more as we enter the age of wearable tech. Smart glasses in particular present an avenue through which sight, the very lens through which people see the world, is mediated through a proprietary digital media device for the sake of capturing and maintaining the consumer’s engagement.

In September of 2021, six years after the Cambridge Analytica scandal that prompted a widespread #DeleteFacebook campaign, Facebook- in partnership with Ray-Ban- released Ray-Ban Stories, the newest iteration of wearable tech (see Fig 1). Touted as smart glasses that are both fashionable and functional, these frames allow users to film their lives in real time and upload what they see to Facebook, Instagram, and every other social media platform. These uploads are mediated through Facebook View, an app that stores all photos and videos uploaded from the glasses. However, Ray-Ban Stories are not Silicon Valley’s first foray into the world of smart eyewear. Stylistically, these glasses are most similar to Huawei’s collaboration with Gentle Monster, presenting sleek, fashionable glasses with heightened functionalities. They do not, however, contain a camera, a Stories feature that is most similar to Snapchat’s Spectacles which are specifically designed to record and share video on Snapchat. Alphabet also attempted to release Google Glass, smart glasses that projected all the functionalities of Search onto its lenses; a concept that proved too awkward for real life. Ray-Ban Stories bridge this gap offering the fashion forward design Ray-Ban is known for with Facebook’s take on smart glasses.

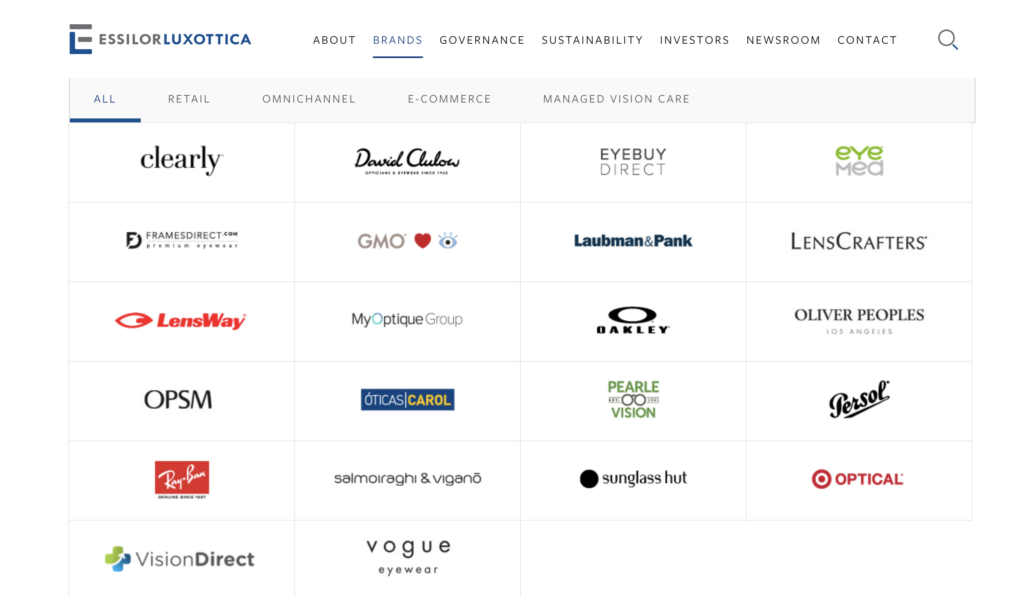

What makes Ray-Ban Stories unique in the world of smart glasses is, as Alex Hern of The Guardian puts it, that “what they represent is significantly more important than what they are”. Ray-Ban may be the brand responsible for marketing the product, but Facebook’s partnership is not with them, but with Essilor Luxottica, the parent company of almost every popular eyewear brand in the western world. Here we will examine the implications of this partnership through two lenses: the Facebook View app, and the role Essilor Luxottica plays in facilitating the accessibility of Facebook’s latest technology.

Facebook View

In order to use Ray-Ban Stories, the user must download the Facebook View app, which should function just as any other basic photo app should by acting as a holding place for images, except that it requires an existing Facebook account. According to the Ray-Ban website “Ray-Ban Stories smart glasses and Facebook View are ads-free experiences, so you won’t see ads when using the glasses or app. And we don’t use the content of your photos and videos for personalized ads. If you share content to any other app, that app’s terms will apply”. One of the fundamental problems with this level of connectivity is that in order to share your images and videos, which is presumably the motivating factor for capturing them in the first place, you need to export your files from Facebook View to a corresponding app. At the moment, Instagram, the single most popular image sharing platform, is owned by Facebook. And so we are required to have a Facebook profile to open Facebook View, where Instagram, a Facebook company, can identify your image as a Ray-Ban Stories image imported from Facebook View. A Facebook-ception, if you will. Herein lies Venturini’s inescapable, proprietary digital infrastructure. In this instance one’s Facebook profile, Instagram profile, type of image, and location of the image is all shared with Facebook, providing the same kind of vast and all-encompassing user profile that fuels its current marketing strategy. Facebook View affords its users the capacity to share their content with their friends, however, it also compromises that superficial ‘ad’free’ promise by forcing the user to engage with external apps.

These technicalities are what Winner identifies as “technolog[y]’s ways of building order in our world” (Winner 127). These seemingly inescapable caveats have created loopholes for companies like Facebook to offer small pockets of encrypted virtual space, while simultaneously making it impossible to extend that notion of privacy beyond a basic, static photo app. It is technically possible to save images on Facebook View without ever sharing them, however, what Facebook have done most successfully is exploit the primary demographic that would be interested in buying these glasses: people who want to share their unique photos. It is in these ways that we are conditioned to accept that companies like Facebook can simply have access to us, because they are selling us something they know we want. A tactic that Facebook is known to do better than anyone else.

Essilor Luxottica

Some of the most consistent hurdles to smart wear popularity are price, style and wearability of the item. Mark Zuckerberg used the Ray-Ban Stories promotional video to assure fashion-conscious consumers that Facebook’s goal “to build best in class glasses” would be best facilitated by “the iconic Ray-Ban frames that people already love” (“Welcome back to the moment. With Ray-Ban x Facebook”, 00:49-00:59). Ray-Ban’s accessible price point and prescription lens option is thanks to Essilor Luxottica, an eyewear titan with a massive client base through its affiliated retail and e-commerce stores, including Sunglass Hut, LensCrafters, and Clearly. Should the partnership prove successful, there is the very real opportunity to begin the process of normalizing the integration of smart technology and affordable, insurable eyewear within other brands beyond Ray-Ban (see Fig 2). Unlike Snapchat Spectacles which are only sunglasses, and Huawei and Gentle Monster which offer a more exclusive and luxury offering, Ray-Ban’s are the everyman’s glasses. They offer transitional prescription lenses that will allow consumers to carry Facebook’s all seeing camera with them all day, and may even have the price covered by their insurance. With this partnership, the ubiquity of smart eyewear is closer than it has ever been.

Conclusion

Facebook and Essilor Luxottica’s partnership is attempting to blur the line between lived reality and shareable content, one where what you see is what you share. According to Zuckerberg, “Ray-Ban Stories are an important step towards a future when phones are no longer a central part of our lives, and you won’t have to choose between interacting with a device and interacting with the world around you” (01:29-01:40). This notion of a more invisible mediating device that allows us to filter our lived experiences through an app is jarring, primarily because, of all tech giants, Facebook carries the most fractured reputation. The consequences of embracing Facebook’s attempt to be the digital partner for the most accessible smart eyewear brand are directly related to its refusal to prioritize the safety of its users. The consequences of the Cambridge Analytical scandal demonstrated the dangers of participating in an app economy that lacks oversight, responsible stewardship, or enforceable policies at the governmental and private corporate level. And as Clark-Parsons note, “every methodological choice produces ethical consequences” (Clark-Parsons 2). The consequences of using Facebook affiliated apps in the past have included compromised personal data and real life political consequences. Given the risk, whether or not consumers will find the ‘hands free’ convenience of these new glasses worth further engagement with the Facebook empire will be decided in the coming months.

Works Cited

Clark-Parsons, Rosemary, and Jessa Lingel. “Margins as Methods, Margins as Ethics: A Feminist

Framework for Studying Online Alterity.” Social media + society 6.1 (2020): 205630512091399–. Web.

“Discover Ray-Ban Stories” Ray-Ban. Web. https://www.ray-ban.com/usa/discover-ray-ban-stories/clp

Hern, Alex. “TechScape: How Smart Are Facebook’s Ray-Ban Stories Smart Glasses?” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 15 Sept. 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2021/sep/15/techscape-smart-glasses-facebook.

Venturini, T et al. “A Reality Check(list) for Digital Methods.” New media & society 20.11 (2018): 4195–4217. Web.

“Welcome Back to the Moment With Ray-Ban x Facebook.” Youtube. Uploaded by Ray-Ban Films, 9 September 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_uOFWU4o3tw&ab_channel=Ray-BanFilms

Winner, Langdon. “Do Artifacts Have Politics?” Daedalus (Cambridge, Mass.) 109.1 (1980): 121–136. Print.