Reclaiming Space: How Young Indigenous People are re-writing the Narrative on TikTok

TikTok is trending as no other app is at the moment. Whether you are on Facebook or Instagram, you’re very likely to come across TikTok’s annoying, but catchy videos. What happens however if we combine catchy and thought-provoking content? Indigenous influencers are re-writing history on our very screens. Written from a Canadian perspective, Michelle Chubb features in this blog entry as inspiring others to take the lead, from their very own home.

McLuhan’s following quote, ‘the medium is the message’, exposes the platform as inherently withholding information rather than the content of the object (McLuhan and Lapham 5). A number of people promote their business, their popularity or raise awareness about urgent issues through social media as it has the capacity to reach a considerable amount of people within seconds. Although the content of the information that spread is important, the social outreach of the latter is more powerful. Focussing mainly on Canadian First Nations, this blog entry aims to compare Clark-Parsons and Ligel’s ethical questions on dealing with marginal communities while presenting a young digital activist’s work, Michelle Chubb, on TikTok.

Historical background

Recently, the Canadian government has revealed that another grave of indigenous children has been found (Honderich). National outrage has prompted the state to undertake further investigations on yet anonymous graves as the sight of dead bodies (children are suspected to have been as young as three) render it incredibly hard to move on this historical aftermath (Ibid.). Throughout centuries, indigenous people worldwide have been abused, dispossessed as well as disenfranchised. Having been forced to assimilate to Canadian culture, generations of indigenous families were punished for speaking their language or practicing their cultural or spiritual rituals in residential schools (Dunbar-Ortiz 18). The ominous past describes why today, many indigenous people are trying to revitalise their culture as their ancestors were restricted on expressing their cultural beliefs. From teaching the Sápmi language to kids in Finland to throat-singing by Canadian Inuit people, all represent small acts of resistance to maintain their cultural practices.

What is … TikTok?

While sitting on our couches was encouraged during lockdown, social media giant TikTok increasingly gained popularity as users scrolled boredom away. The platform consists of 10 to 15-second videos, mostly known for comedy. However, young adults have shown us that education can also reach a significant number of people. For instance, Michelle Chubb, a 22-year old Winnipeg woman, embraces her Cree culture by dressing in her traditional clothes while adding a few pop culture elements. The lack of indigenous people on social media lead the young activist to start her digital career, where she debunks indigenous myths, raises awareness about pressing issues and tries to make her culture more visible.

Through her username, @indigenous_baddie, she alarms that 59% of indigenous women in Canada have contracted HIV through heterosexual intercourse whereas only 16% of indigenous men have it (Chubb) . So far, 10% of the Canadian population have contracted HIV while 5% of it have an indigenous background. The startling numbers originate from sexfluent.ca, a Canadian sex health information community, also present on Instagram, with whom Michelle Chubb has partnered for her videos. The alarming situation falls back to poor economical circumstances, which limits access to healthcare. However, indigenous women are also more often coerced into sex trade, have less guidance or access to sex health information and many of them, having had contracted HIV, breastfeed their babies, transmitting the virus onto their children.

http://www.tiktok.com/@indigenous_baddie/video/7000066948809739525?is_from_webapp=v1

Acts of resistance

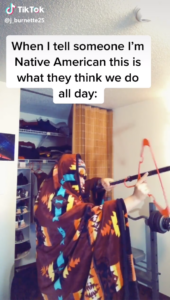

In Scott’s Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance, the peasant communities in a Malaysian village are described as using lies, pretence or secret sabotaging as small tools to resist class division. Resistance does not always need to have a significant impact on society at large, small acts of resistance can also help slightly improve the situation (Scott 12). Similarly, indigenous digital activists such as @indigenous_baddie, @notoriouscree or even the Polynesian social media figure, @melemaikalamimakalapuaa, exhibit ‘everyday form of “micro-activism”’ (Carlson and Frazer 1). Their videos on TikTok (and now also under a new format called Instagram ‘reels’) ’reify dominant power relations’ as they challenge indigenous stereotypes or prejudices (Clark-Parsons and Lingel 1). For instance, figure 2 and 3 present assumptions about indigenous people, which are ridiculed or made fun of on TikTok.

Figure 2

Figure 3

Comedy as well as shedding light on urgent issues help resist the invisibility of indigenous people in not only media, but also literary canons or history books. Clark-Parsons and Lingel describe countercultures as marginal groups aimed at deconstructing discriminating forms of exclusion and build new, inclusive ways to strengthen the community’s identity in ‘mainstream publics’ (Clark-Parsons and Lingel 3). As such, TikTok seems to be the message as it connects the mainstream audience to the ‘performer’. Because of its great outreach, TikTok digital activists are able to re-write the narrative by taking advantage of the platform.

Conclusion

Indigenous TikTok videos help decolonize Western, colonialist perspectives by offering personal stories about growing up indigenous. Through comments or hashtags such as #indigenouslivesmatter or #MMIW (missing and murdered women), digital ‘influencers’ can help spread their message faster than ever. According to Carlson and Frazer, digital activism (under the format of TikTok videos, in this case) strengthens cultural identity, family connections as well as history (Carlson and Frazer 7).

However, social media platforms cannot be described as neutral anymore. Carlson for instance, describes platforms such as TikTok or Instagram as ‘cultural and political territorralization of social media spaces’ (Carlson 15). Content can thus be as political as the engine behind it. Algorithmic bias is till prevalent on the internet and can also have its impact on marginalised groups of people. For example, videos or posts from white people may circulate more dashboards of people, who click more videos featuring white people. Whereas Clark-Parsons and Lingel want to ensure the safeguarding of the data of marginalised people, this blog entry questions how algorithms may play into the outreach of indigenous TikTok videos.

Bibliography

Brohman, E. “Cree woman uses TikTok to connect thousands with her culture.” CBC, 20 Nov. 2020, www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/teen-vogue-michelle-chubb-manitoba-1.5808822

Carlson, B. “The ‘New Frontier’: Emergent Indigenous Identities and Social Media.” The Politics of Identity: Emerging Indigeneity, edited by M. Nakata and M. Harris, Sydney, University of Technology Sydney E-Press, 2013, pp. 12–28.

Carlson, Bronwyn, and Ryan Frazer. “‘They Got Filters’: Indigenous Social Media, the Settler Gaze, and a Politics of Hope.” Social Media + Society, vol. 6, no. 2, 2020, pp. 1–11. JSTOR, doi:10.1177/2056305120925261.

Clark-Parsons, Rosemary, and Jessa Lingel. “Margins as Methods, Margins as Ethics: A Feminist Framework for Studying Online Alterity.” Social Media + Society, vol. 6, no. 1, 2020, pp. 1–11. JSTOR, doi:10.1177/2056305120913994.

Dunbar-Ortiz, Roxanne. An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States. Boston , Netherlands, Beacon Press, 2014.

Honderich, Holly. “Why Canada Is Mourning the Deaths of Hundreds of Children.” BBC News, 15 July 2021, www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-57325653.

Loyer, Jessie. “Indigenous TikTok Is Transforming Cultural Knowledge.” Canadian Art, 13 Apr. 2020, canadianart.ca/essays/indigenous-tiktok-is-transforming-cultural-knowledge.

McLuhan, Marshall, and Lewis Lapham. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. Reprint, Cambridge, The MIT Press, 1994.

Scott, James C. Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance. New Haven, Netherlands, Yale University Press, 1985.

Figures

Mohsin, Maryam. “10 TikTok Statistics You Need to Know in 2021 [Infographic].” OBERLO, 16 Feb. 2021, www.oberlo.com/blog/tiktok-statistics.

Najibzadeh, Arezoo. “Michelle Chubb – 2021 Top 25.” Women of Influence, 2 Feb. 2021, www.womenofinfluence.ca/2021/02/02/michelle-chubb.

Loyer, Jessie. “Indigenous TikTok Is Transforming Cultural Knowledge.” Canadian Art, 13 Apr. 2020, canadianart.ca/essays/indigenous-tiktok-is-transforming-cultural-knowledge.

Videos

Chubb, Michelle. “HIV #facts in Indigenous Communities (Part 3).” TikTok, uploaded by @indigenous_baddie, 24 Aug. 2021, www.tiktok.com/@indigenous_baddie/video/7000066948809739525?is_from_webapp=v1.