Tracking the Stars: Co-star and the Creation of the Digital Celestial

Ayoub Samadi

Introduction

A centuries old practice clad in contemporary systems of information processing. For millenia, astrology has been engulfed in the depths of time and rationality and has not only until recently began to regain the reverence it once had. The reasons for this resurgence will be explored in this paper through the parlance of the modern neoliberal landscape. In particular, the Co-star app’s homepage will be treated as a visual object to critically engage with overarching assemblages which allow it to thrive as a powerful knowledge-generating tool within the contemporary context.

Co-star: Infrastructure & Functionality

According to the website, Co-star is a freemium app which “[…]couples insightful humans with data from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and cutting-edge natural language-AI to give people personalized context for their lives”(Co-star). In other words, the app uses proprietary AI technology to draw out the user’s birth chart from publicly accessible data gathered by NASA’s network. The birth chart itself follows the format of the centuries-old Porphyry astrology system—one of the various astrological chart systems(astro.com). The details of the system itself are not of much importance in this discussion, but what matters here is the fusion of ancient practices with modern techniques of tracking and storing. The app then amalgamates and translates this data to ‘readings’ which are driven by Co-star’s natural language processing software. Moreover, the app also tracks the user’s behavior through Google Analytics so as to personalize the experience and make sure that it is revealing the type of information which would reinforce these patterns. The copywriting on the app’s website cloaks this by claiming it aims to deliver a fully personalized experience, which—in other words, simply serves to increase usage and dependency.

Co-star as visual

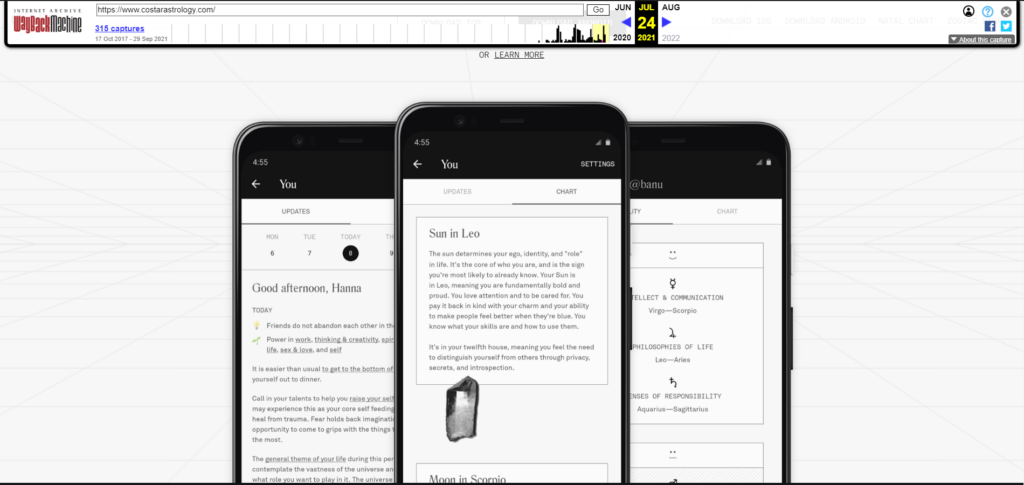

Therefore, it would seem to me that Co-star is fundamentally a data processing software first and an astrologist second. It is through this lens that the app can be looked at as a representational tool made to render this data legible by human subjects. Taking the app’s homepage (see Images below) as a visual object, it becomes clear how this representation occurs. According to Manovich, the practice of infovis entails two key aspects: 1) reduction and 2) spatial variables(38). Firstly, the reduction is so great that the initial data obtained from NASA’s satellites becomes imperceptible. Instead, the mathematical formulations of celestial movement are rendered into a string of text and icons, losing much of the specifics which lie in between this transition. Such is the danger of reduction as it follows an “[…]extreme reduction of the world in order to gain new power over what is extracted from it”(Manovich 38).

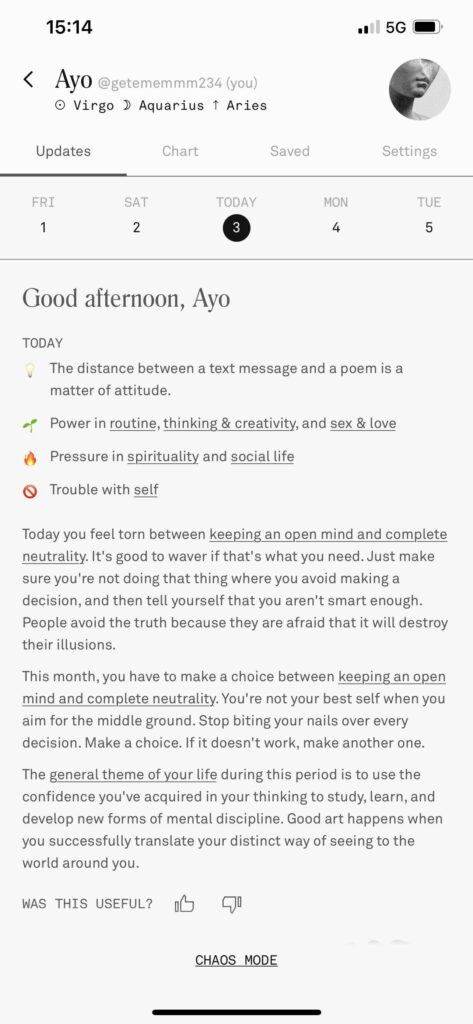

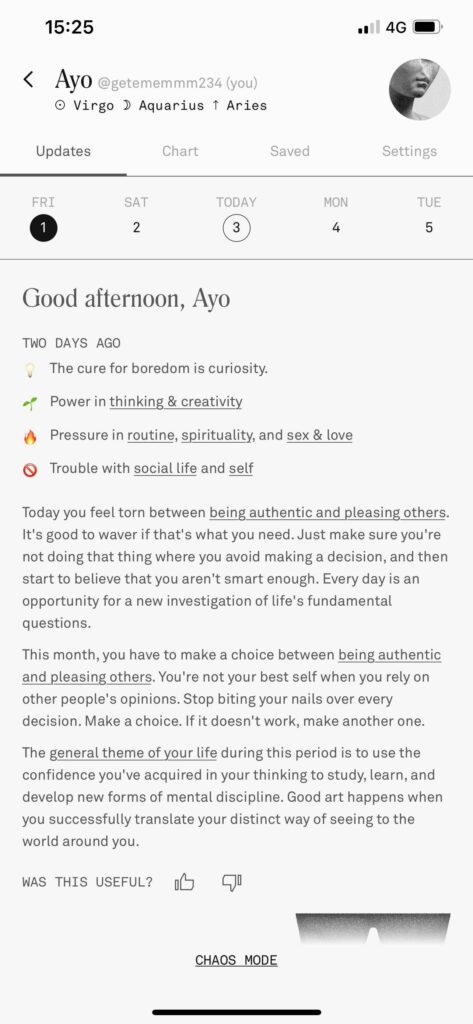

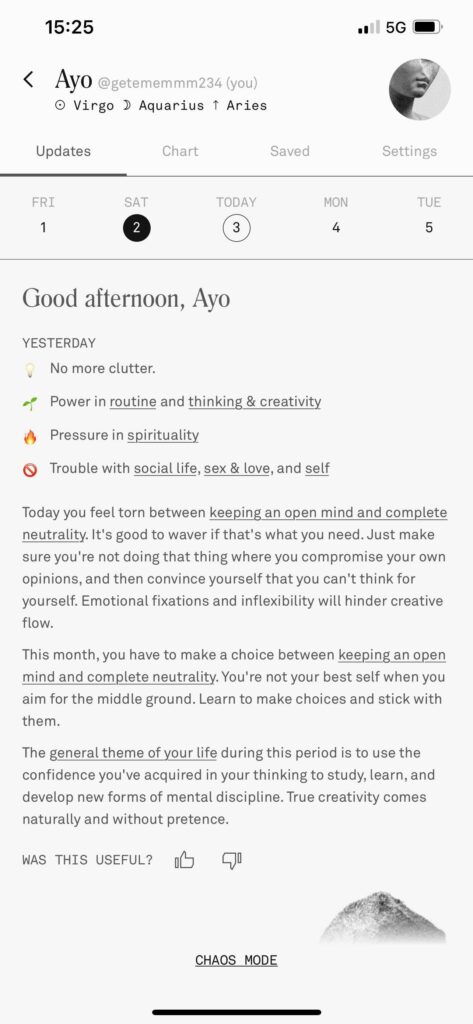

The keyword here is power since, while the app does offer different, individualized results, these results are still framed within the thresholds set by the algorithm for a certain purpose. I attributed intentionality to the latter since the practice of visualization is a purposeful craft which indeed does much sociopolitical work(Kennedy & Hill 5). This leads me to the second of Manovich’s aspects: spatial variables. Comparing the figures below, it becomes clear that certain elements can indeed be seen as spatial variables. Namely, the lightbulb, leaf, fire, and the ‘no symbol’ serve as spatial categorizations which work in tandem with the following strings: routine, thinking & creativity, sex & love, spirituality, social, and self to indicate certain conditions for the specific day. While the text below can differ, it seems that these elements are always present regardless of the day and act as the main guiding variables for the readings. Manovich indicates that spatial variables are often considered as the more important elements of a visual representation and in a way demand to be perceived by their apparent readiness to be viewed (40).

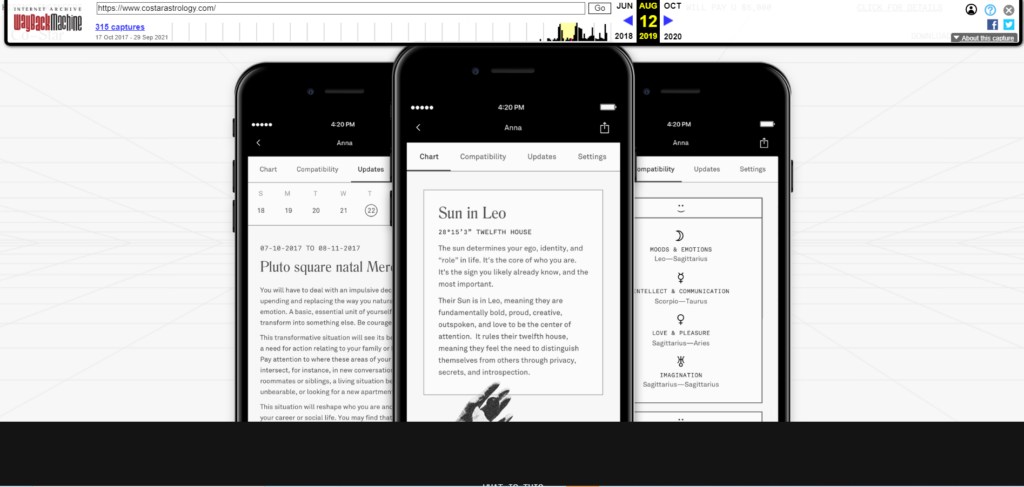

As such, these elements deserve to be looked at by virtue of their intrinsic significance to the app’s functionality. Data visualizations stem from the “[…]decisions and priorities of the people and organizations who make them[…]”, which renders them particularly productive objects in terms of revealing any privileged perspectives and underlying assemblages(Kennedy and Hill 5, 6). Given that the readings are but a representation of amalgamated data, some space is left for the app developers to pursue their own purposes. At this stage Co-star becomes problematic and merits critical inspection. In ‘Scopic Regimes of Modernity’, Jay points towards visuality as a terrain of contestability in which the ebb and flow of several assemblages can be observed (20). Comparing two screenshots taken by archive.org of Co-star’s websites(see below), they seem to be relatively identical except for the homepage shown on the left-most phone. The older version of the app made no mention of the previously discussed spatial variables which have only more recently been adopted so as to improve ‘usability’. In other words, the developers chose to emphasize those variables by virtue of collected analytics.

- Self

- Routine

- Thinking & Creativity

- Social

- Sex & Love

- Spirituality

Conclusion

Therefore, it seems that Co-star is reflective of some sort of paradigm. In particular, the 6 spatial variables(routine, thinking & creativity, sex & love, spirituality, social, self) are quite specific and have been determinedly chosen as a result of sociopolitical and material processes. The reason for this being the contemporary neoliberal context in which elements of everyday life are rendered categorically divisible. In an interview with Cosmopolitan, Banu Guler, founder and CEO of Co-star stated: “Anxiety, loneliness, despair…all of those things are on the up-and-up” (Ortiz). In the context of the United States—undeniably the foremost neoliberal economy—an increasing demand for spirituality can be observed in individual subjects(Lipka and Gegewicz). Further studies have shown a correlation between practices of self-affirmation and coping with stress through the channel of spirituality and in particular, astrology (Lillqvist and Lindeman 206, Van Rooij 986, Tyson 123). The spatial variables provided by Co-star reflect a subscription to various neoliberal assemblages by reinforcing its ideal of a productive, working individual who draws distinctions between work and leisure/social life. Co-star is a response and an ode to neoliberalism. Moreover, the app’s very infrastructure is dictated by the neoliberal context through its association with silicon valley and deep algorithmic dependence on discrete data. Astrology, at the end of the day, is not a practice which can be rationalized, let alone attempting to appropriate it into the contemporary neoliberal landscape.

Works Cited

Co-star. “Co – Star: Hyper-Personalized, Real-Time Horoscopes.” Www.costarastrology.com, www.costarastrology.com/faq/. Accessed 3 Oct. 2021.

Delgado, Carla. “Why Are People so into Astrology Right Now?” Discover Magazine, 25 Aug. 2021, www.discovermagazine.com/mind/why-are-people-so-into-astrology-all-of-a-sudden.

Jay, Martin. “Scopic Regimes of Modernity.” Vision and Visuality, Seattle Bay Press, 2009, pp. 3–23.

Kennedy, Helen, and Rosemary Lucy Hill. “The Pleasure and Pain of Visualizing Data in Times of Data Power.” Television & New Media, vol. 18, no. 8, Sept. 2016, pp. 769–82, https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476416667823.

Lillqvist, Outi, and Marjaana Lindeman. “Belief in Astrology as a Strategy for Self-Verification and Coping with Negative Life-Events.” European Psychologist, vol. 3, no. 3, Sept. 1998, pp. 202–8, https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040.3.3.202.

Lipka, Michael, and Claire Gecewicz. “More Americans Now Say They’re Spiritual but Not Religious.” Pew Research Center, Pew Research Center, 6 Sept. 2017, www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/09/06/more-americans-now-say-theyre-spiritual-but-not-religious/.

Manovich, Lev. “What Is Visualisation?” Visual Studies, vol. 26, no. 1, Mar. 2011, pp. 36–49, https://doi.org/10.1080/1472586x.2011.548488.

Ortiz, Jen. “Meet Banu Guler, the CEO of Co–Star (You Know, That Astro App That Drags You on the Daily).” Cosmopolitan, 10 July 2019, www.cosmopolitan.com/lifestyle/a28241507/co-star-astrology-app-push-notifications-banu-guler/.

“Overview House Systems.” Www.astro.com, www.astro.com/faq/fq_fh_owhouse_e.htm.

Scofield, Bruce. “ASTROLABE: Why I Use Porphyry.” Alabe.com, alabe.com/text/PORPHY.html. Accessed 3 Oct. 2021.

Tyson, G. A. “People Who Consult Astrologers: A Profile.” Personality and Individual Differences, vol. 3, no. 2, Jan. 1982, pp. 119–26, https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(82)90026-5.

van Rooij, Jan J. F. “Introversion-Extraversion: Astrology versus Psychology.” Personality and Individual Differences, vol. 16, no. 6, June 1994, pp. 985–88, https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(94)90243-7.

“Wayback Machine.” Archive.org, 2019, web.archive.org/.