Plan (Your) Obsolescence – Archive (as) Art

This article is a co-creation by Autumn Hand, Juliana Paiva, Kendall Grady and Mario Gesteira.

Archive (An Informal Introduction)

Let’s blow the dust and grime off the archive. Let’s get to the art of this matter too.

Whether archive evokes a bourgeois, elite, stuffy academic notion of a hidden-away trove of esoteric knowledge — or rather, an encrypted database structured as an expansive file tree of digital information — the archive is not usually understood as a vital and dynamic foundation for creativity and artistic venture.

Indeed, “Past centuries aimed only to polish and perfect the great archaic ideas” (Zielinski, 3). There was such a time when ideas were meant to be collected, stored and (only sometimes) added to. This way of thinking has since turned around; “Do not seek the old in the new, but find something new in the old” (Zielinski, 3). Such a reconceived approach to the archive has been auspicious for the artist.

Archives can contain things that illuminate thinking in new ways. Such is the stuff of the artist.

To engage with the ‘illuminated’ archive is to reuse, reinterpret, reimagine and repossess the archive. To pursue the archive as art is to approach databases, systems, libraries and collections of all constructs or iterations and then construct and contextualize (deconstruct / reconstruct, contextualize / recontextualize) this content. This is archive (as) art.

With regard to the writings of Siegfried Zielinski, Peter Krapp, Sven Spieker, Christiane Paul and Garnet Hertz with Jussi Parikka– and their respective works on New Media, Art and the Archive– several themes can be extracted when considering an approach to the archive (as) art. These are fluid ideas, that blend and merge with one another… but also serve as a loose way of categorizing archive (as) art.

p

Themes: When We Think of Archive (as) Art, We Think of…

p

Reality / Possibility

The archive is a layered, compounded and buried history. A mass of potentials. Networks within networks. The artist takes a role as archaeologist, or rather anarchaeologist (using systematic nature of the archive against itself). This is archaeological flaneurie.

Order /Disorder

Order is a limitation. Consider, “…the most exciting libraries are those with such abundant resources, it is impossible to organize them” (Zielinski). It’s about looking at the books on the shelf next to the one you’re looking for.

Memory

“Memory is not an archive, nor is an archive a memory bank. The documents in an archive are not part of memory; if they were we should have no need to retrieve them; once retrieved. They are often at odds with memory” (Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi qtd. Spieker). In the same vein, “Recollection becomes oblivion, the interface-principle WYSIWYG becomes WYSIWYF: what you see is what you (for)get” (Krapp). Archive reveals not what we know, but what we don’t know.

Navigation

Navigation through content may or may not be linear. The narrative, hyperlink or relational approach that one can apply to content opens space to multiple possibilities and exponential interpretations. The way the content is presented and controlled influences the experience of the user with that content.

Planned Obsolescence

‘Planned obsolescence’ is the idea that all goods should be disposable and dispensable (whether through physical breakdown or fashionable trend). When planned obsolescence is confronted by archive, a trope reminiscent of the Law of Thermodynamics applies. Just as energy can not be created nor destroyed; Media (in any archive, in any sense) exists and does not die (Hertz and Parikka, 13).

p

Plan (Your) Obsolescence; A Curatorial Statement

As the scope of the artist is applied to archive, a rich and dynamic lineage manifests. Art has been part of the archive (museums, cabinets of curiosity, libraries, and collections). Archive has been part of art (as seen in works of Dadaist, Surrealists, or any other disguised artworks which undertake data or document).

Since the ubiquity of the Internet and omnipresence of digital media, the pervasiveness of archive has never been so perceivable as it is now. Personal photo albums appear daily before us on Facebook, where timelines narrate a collection of postings, communications and updates. Platforms like Facebook (such as YouTube, Flickr, WordPress and Tumblr) preserve and publish our videos, photos, and words. Institutions now also network and digitize, unfurling their once hallowed troves of information and knowledge. This content and more is valued and commodified by corporations, governments, and certainly artists too.

Of all the many things you make and do and see and hear; How much of this gets archived? What is archived by you? Who has access to your archive? When do you retrieve your archived articles (-ever)? Why are we surrounded with documentation? Where does it all go?

Planning your obsolescence is an exercise in subjective archiving. Like word reclamation that has been performed by American American or LGBT communities, planned obsolescence takes connotative control of the black box imposed by commercial enterprise, societal pressure and the limitations of materiality. This tactical approach acknowledges the archive while allowing for freedom and individualization. The artists in Plan (Your) Obsolescence seize the means of production by vehicle of media archaeology, excavating the self toward new relational truths and embodiments. In planning their obsolescence, these artists engage immortality as a byproduct of the creative process.

p

Plan (Your) Obsolescence Works:

p

The Whale Hunt

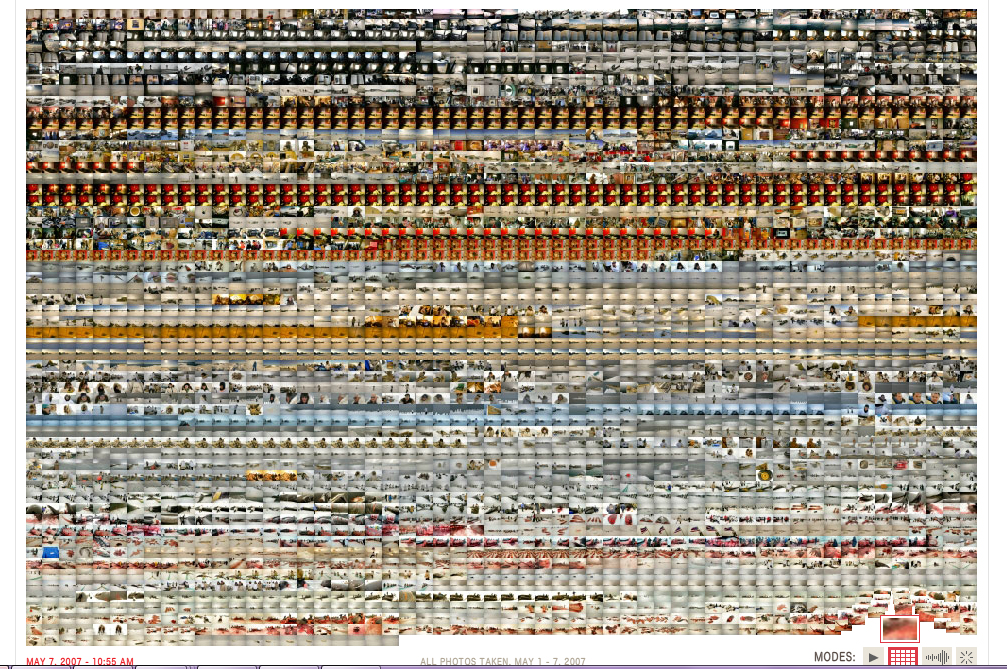

Jonathan Harris, The Whale Hunt – An experiment in human storytelling (2007)

The Whale Hunt documents one man’s first-hand experience of a thousand-year-old tradition. Harris saturates the viewer with 3,214 photographs beginning with his taxi ride to the airport and ending with the butchering of the second whale seven days later.

Harris’s photographs spin moment-to-moment narratives that morphs contingent upon the way they are viewed. With a few clicks on an interface, an epic event in the life of an individual may be refocused, reconstructed and retold. Harris allows viewers to ‘read’ the images across topic (children, blood or whales), aesthetics (color) or time (hour, date or frequency).

In Harris’s whale hunt, the obsessive singularity of Moby Dick becomes the object of every viewer’s deconstruction, a story to be told and retold rather than canonized.

p

Pockets Full of Memories

George Legrady, Pockets Full of Memories (2001)

Pockets Full of Memories creates an anatomical archive of personal value by inviting visitors to digitally contribute an object in their possession (pockets) to the artwork. The participants scan their selected item at a scanning station and answer a set of questions regarding the object, rating it according to certain attributes; old/new, soft/hard, natural/synthetic, functional/symbolic, personal/non-personal, useful/useless, and so on.

Based on the participant’s input, an algorithm classifies each object and positions it accordingly on a screen display. Users can review each object’s data and add their own personal comments and stories.

Pockets Full of Memories is an archive of objects and memories collected by one person (the artist), but the archive consists not only of data from different people, but also their own memories, realities and values.

p

A Series of Unfortunate Events

Michael Wolf, A Series Of Unfortunate Events As Presented By Google Street View (2011)

Photographer Michael Wolf spent hundreds of hours in front of the computer as a flaneur inside Google Street View looking for strange events that happened or were about to happen. Whenever he encountered such an incidents, he would photograph his screen (with a camera — not a screen grab!) thereby reiterating, reformatting, and ultimately archiving the incident. His collection led to the photo series A Series Of Unfortunate Events As Presented By Google Street View.

This piece is an archive of daily events first recorded randomly by Google Street View, then troved and interpreted by Wolf. This piece is archaeological and also reconstructs the narrative by taking the (unfortunate) events out of the context, (re)archiving and regrouping them.

p

Flickeur

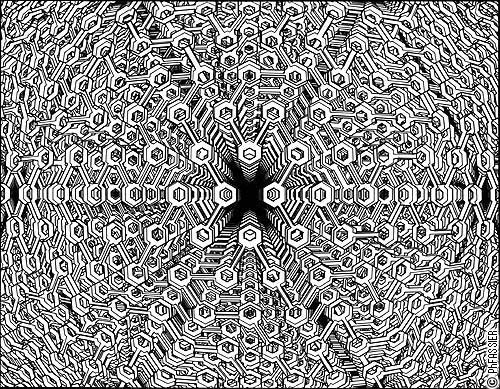

Mario Klingemann, Flickeur – Pronounced like Voyeur (2006)

Flickeur is an artwork that randomly retrieves images from Flickr.com and creates an infinite film with a style that can vary between stream-of-consciousness, documentary or video clip. Every picture, blend, motion, zoom or timelapse are completely random. Flickeur works like a looped magnetic tape where incoming images will merge with older materials and be influenced by the older recordings’ magnetic memory.The virtual tape will also play and record forward and backward to create another layer of randomness.

In this piece, the algorithm of Flickeur randomly harvest images from Flickr and repuropses them in a false memory archive for the viewer, furthermore reassembling images from different contexts, constructing new narratives. A new ephemeral archivization is exposed. Flickeur addresses an order/disorder of assemblage and an anarcheological conception of the otherwise coveted and often personal pictures on Flickr. A total exploitation of archive potential.

p

Reconstruction of Brain Activity

The Gallant Lab at UC Berkley, Reconstruction of brain activity (2010)

UC Berkeley scientists built a system that captures visual activity in the human brain and reconstructs it as digital video image. The subject’s brain is scanned in the functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging system (fMRI) while she watches a video compiled from different Hollywood movies (see left frame in the video above). This archived data is rendered as a second video. The videos are then matched to determine which Hollywood image provoked which neurological image.

The system gathers brain activities that where once black-boxed by scientific capabilities and interpretive understanding, opening them to a new assemblage of color, texture and narrative. The emergent archive is neither Hollywood nor neurology, but a translation of both into another story (see right frame in the video above).

p

_____________________________________________________________________________

Authors’ Note

The museum, like the library or the registry, and other institutions, is an archive. Above, we’ve meditated on all the ways that an archive and its components can be deconstructed, circuit bent, visualized, surprised by fortuitous events, and informed by daily life or singular events– dead media or digital technologies. This begs the question, “What is the future of the museum?”

As a supplement to this article, curation, and our general curiosities we recommend reading Night of the living dead: Future Museum; A review about the lecture /debate concerning Future of Museum.

_____________________________________________________________________________

Bibliography

Hertz, Garnet and Parikka, Jussi. “Zombie Media: Circuit bending archaeology into an art method”. 2010.

Krapp, Peter. “Hypertext avant la lettre”. New Media old Media. 2006.

Paul, Christiane. “Database Aesthetics”. Minneapolis: The University of Minnesota press, 2007.

Spieker, Sven. “The Big Archive”. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2008.

Zielinski, Siegfried. “Deep Time of the Media”. Cambridge: The MIT press, 2006.

Art Works

The Whale Hunt. Jonathan Harris. 2007. TheWhaleHunt.org. 29/02/2012.

<http://thewhalehunt.org/>

Legrady, George. “Pockets full of memory, 2001”. George Legrady.com. 2001. 29/02/2012.

<http://www.georgelegrady.com/>

Legrady, George. “George Legrady Pockets Full of Memories: Linz”. Youtube. 2007. 27/02/2012.

<http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=iYjYyc78XJw>

Legrady, George. “Chanel from glegrady”. Youtube. 2006. 01/02/2012.

<http://www.youtube.com/user/glegrady>

Casper, Jim. “A Series of Unfortunate Events”. Lens Culture.com. 2011. 12/03/2010.

<http://www.lensculture.com/wolf-asoue.html>

Michael Wolf Photography. Michael Wolf. 2012. Michael Wolf Photography. 29/02/2012.

<http://www.photomichaelwolf.com/street_view_unfortunate_events/index.html>

Mario Klingemann. “Flickeur”. 2006. 28/02/2012.

<http://incubator.quasimondo.com/flash/flickeur.php>

Jack Gallant. “The Gallant Lab at UC Berkley”. 2012. Google Sites. 10/03/2012.

<http://gallantlab.org/>

Diaz, Jesus. “Scientists Reconstruct Brains’ Visions Into Digital Video In Historic Experiment”. Gizmodo.com. 2011. 28/02/2012.

<http://gizmodo.com/5843117/scientists-reconstruct-video-clips-from-brain-activity>

Further Resources

Huhtamo, Erkki and Parikka, Jussi. “Media Archeology”. California: The Regents of the University of California, 2011.

Lovink, Geert. “Interview with German media archeologist Wolfgang Ernst”. Nettime maillist archive, 2003.

Manovich, Lev. “The Language of New Media”. Cambridge: The MIT press, 2001.