Notes on Paul Virilio’s War and Cinema

This is a summary of Virilio’s book, War and Cinema: The Logistics of Perception. I read this for a class on German Media Theory – alongside Elias Canetti’s Crowds and Power, Klaus Theweleit’s Male Fantasies and Friedrich Kittler’s Gramophone, Film, Typewriter. I guess it is strange to ‘relocate’ Virilio (a French theorist) like this, but his study of “the deadly harmony that always establishes itself between the functions of eye and weapon” fits in well with the mass psychology and focus on war in Canetti’s and Theweleit’s books, and with Kittler’s media archeology.

This is a summary of Virilio’s book, War and Cinema: The Logistics of Perception. I read this for a class on German Media Theory – alongside Elias Canetti’s Crowds and Power, Klaus Theweleit’s Male Fantasies and Friedrich Kittler’s Gramophone, Film, Typewriter. I guess it is strange to ‘relocate’ Virilio (a French theorist) like this, but his study of “the deadly harmony that always establishes itself between the functions of eye and weapon” fits in well with the mass psychology and focus on war in Canetti’s and Theweleit’s books, and with Kittler’s media archeology.

There seem to be a number of critical assessments of War and Cinema on the Web; here I pick out some of the key points in Virilio’s argument and use examples to show how his work (written more than 20 years ago) is still relevant today.

Virilio traces a co-production of military and cinematic techniques and technologies, from the mass production of aerial photography and cinematic propaganda to modern flight simulators and weapons that “open their eyes” (e.g. laser guided missiles). All of this falls under the logistics of perception – more than just prosthetic or removed from the body, vision is the result of a detailed coordination of complex operations, a technological exercise that requires planning, material support, engineering, and so on.

Shock and Awe: no war without representation

The first rule or principle Virilio outlines is that there is no war without representation. As scientific and meticulous as war becomes, it never breaks from the ‘pre-technical’ ideas of war as deception and illusion, spectacle and captivation. So in addition to maps and planning (representations of the battlefield) there are mediations such as the piercing sound of swooping planes and missiles, designed to paralyze their soon-to-be victims. What was previously called the “theatre of operations” has been replaced by the “theatre weapon” (7).

Looking to cultural and economic ties between the industries, Virilio argues that cinema fits perfectly within the war machine: he cites, for example, arms industry funding of the German film company UFA in the 1930s, and the role of cinema stars and directors during the two World Wars (in propoganda, but also selling war bonds, etc.). Conversely, he writes that the war machine – with its focus on mass-management over diverse locales, logistics and planning – fits with cinema, and points to the scaling-up of production for films like Birth of a Nation.

What defines cinema, Virilio writes, is not the production of images but their manipulation: pans and tracking shots, zooming in and out, editing, etc. Cinema is the manipulation of dimensions, producing depth through movement. As has been noted by artists and writers before Virilio, this aligns the experience of watching movies with that of flying. And while pioneer directors were coming to terms with this unique aspect of cinema, he argues, aviation in the early 20th century became less about breaking speed records and more about a new way of seeing.

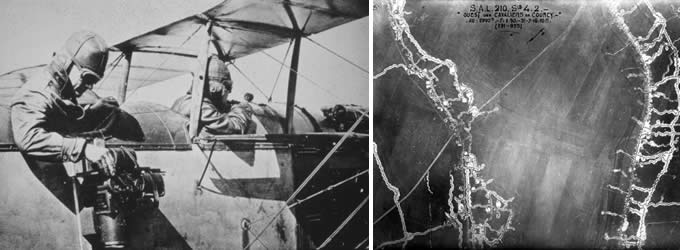

Aerial photography was introduced during the American Civil War (via hot air balloons), but came into its own during the first World War. It epitomizes Virilio’s logistics of perception, in that it requires a large-scale operation, including planning and post-production.

In light of Virilio’s argument, it is fitting that Google Earth (which uses satellite imagery rather than aerial photography) now includes a flight simulator. As if the experience of hovering over a 3-D image of the earth was not cinematic enough, there are now plenty of Google Earth ‘movies’ on YouTube, complete with soundtracks.

The cinematic manipulation of dimensions has its precedent in the rifle scope. “In his pencil-like embrasure, the look-out and later the gunner realized long before the easel painter, the photographer or the filmmaker how necessary is a preliminary sizing-up. This action, like the seductive wink so fashionable in the thirties, increased the depth of the visual field while reducing its own compass” (49).

Such negation or elimination of distance, for Virilio, continues into cinema and on to simulation: writing about Disneyland’s City of Tomorrow and one of its signature films, ‘Around the World in Eighty Minutes’, he says that “in the thirties, it was already clear that film was superimposing itself on a geostrategy which for a century or more had inexorably been leading to the direct substitution, and thus sooner or later the disintegration, of things and places” (47).

The substitution of places of war goes hand in hand with shifts in technologies of perception: in order to escape the look-out’s view and that of aerial photography, “the army began to bury its strongholds and outworks in a third dimension, throwing the enemy into a frenzy of interpretation. Invisible in its sunken depths, the camera obscura also became deaf and blind, its relations with the rest of the country now depending entirely on the logistics of perception, with its technology of subterranean, aerial and electrical communication”. Virilio writes that the “fortress-tombs, dungeons and bunkers are first and foremost camera obscurae … Their hollowed windows, narrow apertures and loopholes are designed to light up the outside while leaving the inside in semi-darkness” (49).

The substitution of places of war goes hand in hand with shifts in technologies of perception: in order to escape the look-out’s view and that of aerial photography, “the army began to bury its strongholds and outworks in a third dimension, throwing the enemy into a frenzy of interpretation. Invisible in its sunken depths, the camera obscura also became deaf and blind, its relations with the rest of the country now depending entirely on the logistics of perception, with its technology of subterranean, aerial and electrical communication”. Virilio writes that the “fortress-tombs, dungeons and bunkers are first and foremost camera obscurae … Their hollowed windows, narrow apertures and loopholes are designed to light up the outside while leaving the inside in semi-darkness” (49).

Directors and Dictators

At different points in the book, Virilio draws comparisons between stars and pilots, and between directors and dictators. Cecil B DeMille and others displayed “a charismatic infallibility stemming from foreknowledge of scripts which, as it happened, sometimes did not exist. For a whole generation of cinematic miracle-workers, the process of direction, even if improvised, literally took the form of revelation — that is divine action which makes konwn to men truths that they would not be able to discover by themselves” (52).

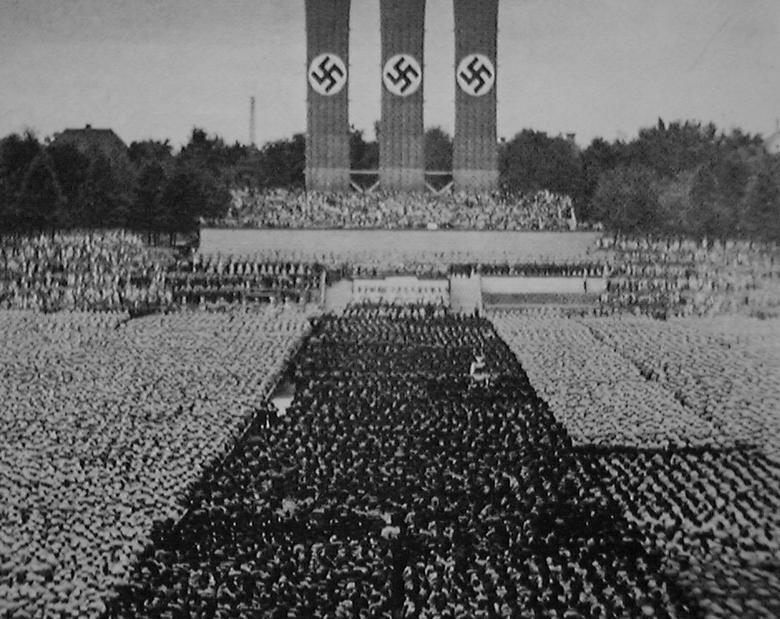

“At the same time … a new breed of military and revolutionary leader was beginning to have a similar charismatic effect on the masses. These men were heralds of the trans-political era: since real power was now shared between the logistics of weaponry and of sound and images, (in other words) between war cabinets and propoganda departments … parliamentary power had disappeared” (52-53)

Hitler’s plan for a new German empire required a “transformation of Europe into a cinema screen” (53). He looked “to relaunch the war as an epic” (54). A major factor was propaganda: the conference from Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will was entirely fabricated for the screen – everything was set up and performed with reference to the camera.

A Traveling Shot over 80 years

In the final chapter, Virilio (re)traces what he calls the fusion/confusion of technologies of perception and of warfare. He starts anew, this time with the introduction of searchlights in the Russian-Japanese battle of Port Arthur in 1904.

These searchlights were war’s first projectors – they “illuminated a future where observation and destruction would develop at the same pace. Later the two would merge completely … above all [with] the blinding Hiroshima flash which literally photographed the shadow cast by beings and things, so that every surface immediately became the war’s recording surface, its film” (70).

The searchlight was a reaction, of course, to war being waged from the air. It was an extension of what Virilio calls “the deadly harmony that always establishes itself between the functions of eye and weapon,” a truth ominously expressed years earlier in Etienne-Jules Marey’s chronographic rifle. Meanwhile, the military would develop a range of invisible weapons devoted to making things visible. This included the radar picture, but today we might also think of things like smart dust, used to remotely sense troop movement in the desert.

After Port Arthur, total war inverted conventional strategic planning. Virilio writes: “in the wars of old, strategy mainly consisted in choosing and marking out a theatre of operations, a battlefield, with the best visual conditions and the greatest scope for movement. In the Great War, however, the main task was to grasp the opposite tendency: to narrow down targets and to create a picture of battle for troops blinded by the massive reach of artillery units, themselves firing blind, and by the ceaseless upheaval of their environment” (70).

That is, trenches, shell-shock, moving front lines, the destruction of landmarks and so on, all impeded vision in one way or another. This necessitated the mass production of aerial photographs, of a new logistics of perception.

Virilio writes that the “deadly harmony between the functions of eye and weapon”, or the fusion and confusion of these operations, seems complete now as weapons “open their eyes” – examples include “heat-seeking missiles, infra-red and laser guidance systems, warheads fitted with video cameras” (83). A corollary of this for pilots is that they are trained to distrust their own eyes – Virilio points out that the significant moment has passed, in which flight simulation hours are officially recognized as on par with real flight hours for training.

—

In conclusion, I’ll just say that it is not hard to see how Virilio’s arguments extend to the current War on Terror, where an unseen threat has gone hand in hand with unprecedented levels of U.S. secrecy and spying. Not to mention the nature of terrorism designed with mass media in mind.

Meanwhile, the searchlight with which Virilio began, remains an iconic presence in nearly every major city, and of course in the culture of cinema. Most eerily of all, though, was perhaps the use of 88 high powered search lights for the 9/11 Tribute in Light memorial.