Review of Digitizing Race: Visual Cultures of the Internet

Lisa Nakamura’s book Digitizing Race and Culture: Visual Cultures of the Internet covers a range of issues involving race and gender on the internet. Nakamura is an associate professor in the Institute of Communication Research with a joint appointment in Asian American studies at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign.

She begins by giving a historical background of race in American politics in the nineties. During the Clinton-Gore administration, a new movement of neo-liberalism brought about racial “colorblindness”. The idea being that it would be more progressive to avoid the subject of race and not address racial differences in politics. By omitting racial discussion during the emergence of the internet, relevant research of race on the internet was never produced.

Instead of covering blatant racism by hate sites and focusing on the more radical case studies, Nakamura covered five very different areas involving race and gender on the web. In the first chapter she discusses the visual culture of AIM buddies. AOL Instant Messenger graphic icons are hugely popular on the internet. Many websites are just for the creation of these icons. Users especially like to take part in creating these icons and many have racial identities attached to the icon such as an animated GIF of a cartoon girl wearing an all American flag outfit with the words “Never 4get 9-11.” These user generated icons visualize the need internet users have of identifying themselves based on race and culture to their peers on the web.

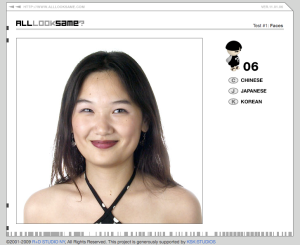

Nakamura then introduces the website www.alllooksame.com where users take a quiz by guessing if the person on the screen is Chinese, Japanese, or Korean. Many Asians think they are able to distinguish between different Asian nationalities but the average person who takes the quiz gets 7 out of 18 images right. This average low score proves that one cannot make judgment based on visual representation of a person (I am of Japanese descent and got a 6/18). I find this website extremely interesting because advertisers or companies are not profiling people, rather the user initially profiles the person and surprisingly discovers that race is more complicated than previously thought.

“Users of alllooksame.com bulletin boards commiserate with each other about their low scores; and importantly, the low scores that most users get confirm that seeing is not believing- the “truth” about race is not a visual truth, yet it is one that is persistently envisioned that way. Alllooksame.com is an apparatus that deconstructs the visual culture of race.”

Within this chapter she also discusses the problem with language and how racism occurs with language due to web biases towards English as the main language for the web. As a case study, she discusses the language divide in a country like India. It is very costly to type in a language like Hindi, therefore many who do not speak another language other than Hindi are left out of cyberspace and even those that speak English has to give up “ typographical purity of Hindi to enter the digital commons. Thus the internet will produce impure or inauthentic expressive forms.”

Nakamura also covers how race in cyberspace is portrayed in film and advertisements. She illustrates the problems with the “whiteness” of the users engaged in high technology in The Matrix Trilogy and The Minority Report. She also discusses Apples famous ad campaign where alpha channeled images in black of people are dancing with their sleek white ipod. Although all the images of the people are completely silhouetted in black, Nakamura argues that race is still represented by stereotypical signifiers based on their clothes, type of music, and attire.

In the fourth chapter, the focus shifts towards feminism when Nakamura introduces www.babydream.com. Just in the past few years, pregnancy websites, forums, and discussion boards have gained popularity for women who are trying to conceive, pregnant, or just given birth. These are websites where women can discuss hopes, fears, problems, and progress of being pregnant and giving birth. This is a very interesting way of studying femininity and race because all of these women have graphic images or real pictures portraying the pregnant status in a visual way. Similarly to the AOL Instant Messanger icons, pregnant women can create their identity by creating an image or choosing from images that most favorably represents them visually. These pregnancy websites can be studied to understand activity of a sub-genre of women on the web.

Finally, Nakamura studies the measurement of race on the web. She discusses the many problems and stereotypes that are involved with web activity among minorities. For example, Asians are considered one of the “model minority” groups and considered to be among the more fluent in technology and more involved in the web. However many studies that prove these results are based on phone interviews in English, thus only taking in to account a small English speaking Asian population and leaving out the rest. This chapter clearly brings about the errors in the ways that research on demographics is performed on the web.

“Many of these surveys design questions that hew to this paradigm by querying respondents on what types of services and activities they engage in, rather than asking them about their cultural production, such as postings to bulletin boards or creation of Web sites or other forms of Internet textuality or graphical expression. Thus Internet use by racial minorities may be misunderstood as being on a par with usage by the white Internet majority in the United States if “access” is the only criterion considered.”

Without asking the right questions when doing web research and going about the research in a multilingual and broader medium, it is difficult to really know which demographics participate in the web and in what way they engage with the internet.

Lisa Nakamura’s research on race and the web is thorough, diverse, and thought provoking. I was glad to discover the different variety of web based race research through film, advertisements, pregnancy bulletin boards, instant messenger, and race based websites. I was fascinated by the way language contributes so largely to race and racial representation on the web and would like to have read more developed research on language and demographics. I found the last chapter to be the most intriguing since it deals with current problems of web demographic research and ways to improve our current study on the web in order to collect a more accurate portrayal of race on the internet.