Locative media: mapping movement trough the city

Locative media genre can evoke uneasy feelings due to its military origin and ties to corporate power trough funding. There is a significant difference between subversive appropriation of the locative media tools such as in art practices and their military or corporate applications of control and management.

This ‘uneasiness’ was strongly felt around CITYWARE – a platform developed for the sake of an academic research but that has come across as a surveillance tool, therefore blurring the line between corporate (data mining) and academic interests. The project has been heavily criticized, it has opened all sorts of questions about privacy and tracking of consumers behavior and, was even mentioned in one of Wiki’s article in WikiLeaks section

The platform CityWare was developed at the University of Bath, as a tool for social analysis of the way social network functions within the city, or how people move within urban spaces. It enables live data analysis trough collecting data both on and off line, then linking and synchronizing it for further use. It works as a combination of: 1. Facebook (CitiWare participants come from subscribing to CityWare Facebook application) 2. Bluetooth enabled devices (after subscribing to Cityware Facebook application, users turn on their Bluetooth to enable tracking /leaving ‘traces’ in the city) and 3. CityWare nodes/servers installed at different point in the city (which scan ‘mobility traces’ of the participants, trough their Bluetooth id). The way it works is that every time you encounter another Bluetooth device within range of a node the data is uploaded to Facebook. On their subscription pages, Facebook-CityWare users could see graphs of people they most recently interacted with or spent the most time with or met more frequently.

Gary Cutlack wrote about the platform for TechDigest: “ The only problem is no one asked for the permission of some of the the scanees – so anyone with their phone’s Bluetooth powers enabled risks having their movements tracked by the freely-available Cityware software. Not such a big deal, says Cityware, as no data linking individuals to their movements is recorded, so there’s no way of telling who went from Starbucks to the library at 10.45am yesterday…”

The Guardian reported pretty much the same issue.

Project head Eamonn O’Neill, in an interview for Time Higher Education ’reassured’ us that collected data “have been stored securely and used only for our research purposes. The notion that any agency would seriously consider Bluetooth scanning as a surveillance technique is ludicrous.”

In one section of the project description text developers suggest potential use of the platform as: “ invaluable source for understanding how mobility and encounter patterns can help in diffusion of ideas, innovations and viruses”…and further in the text..” thus local or national government can use such data to develop and evaluate immunization strategies to combat biological viruses”. (Urban Informatics: The practice and promise of real time city, 2008)

I will leave this for contemplation…

But it made me think (beside about new controversial vaccine scare) how locative media art is ultimately about biopower. And it made me think of a completely different kind of locative media project, dealing with movement trough the city in a very different way– Biomapping.

BioMapping was developed in 2004 by Christian Nold. It is conceived as a community mapping project where participants are wired up with a device recording their Galvanic Skin Response (GSR), “a simple indicator of the emotional arousal in conjunction with their geographical location”. People re-explore their local area by walking the neighborhood with the device and on their return a map is created which visualizes points of high and low arousal. By interpreting and annotating this data, communal emotion maps are constructed that are packed full of personal observations which show the areas that people feel strongly about and truly visualize the social space of a community.”

Biomapping emerged as a critical reaction to what was recognized as the dominant trend “which aims for computer technology to be integrated everywhere – including our everyday lives and even bodies.”

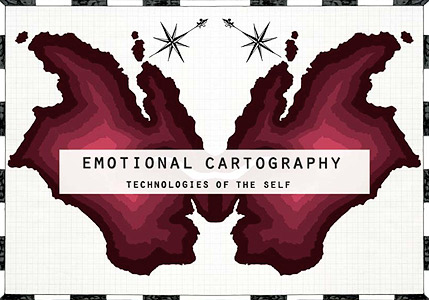

In April 2009, the book was published (and edited by Christian Nold ) under Creative Commons: Emotional cartography – can be downloaded here http://emotionalcartography.net/

It is a collection of essays from artists, designers, cultural researcher, psychogeographers and futurologists– dealing with social and cultural implications of visualizing people’s intimate biometric data and emotions using technology.

We may be able to navigate by ‘feeling’- looking on our maps of the city, and our Biomap, and seeing how different areas ‘feel’, says Christian Nold.

In this locative media project we see a different ways of augmenting physical space, to speak in Manovich terms. Communication and mobile technologies add another layer to the physical space. This converging space, a hybrid space or whatever we call it – is an information space. And it also functions as a public space. Biomapping tool adds different kind of layer to the city, and to its “emerging virtual geography”. It enables people to map their own experience onto the space, rather than monitoring their behavioral patterns, as in the first project.