About Ashiq Khondker

M.A - New Media, Universiteit van Amsterdam; B.S - Liberal Arts, The New School, NY.

I forrestgump about the creative world, like where's waldo in the art fair circuit. I should write more, but I'm absorbing it all until my closet artist's got enough ammo.

Websitehttp://defunct.

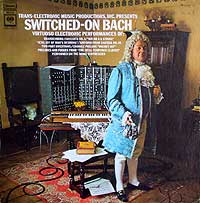

What would life be without Bach? Far from any discussion of the aura, the only reason I have ever heard Bach is that his compositions have been relentlessly copied, passed down the generations, re-interpreted, re-adapted for new instruments (piano, electric guitar,

moog), and let to remain free in the public/sonic sphere.

A dear friend and huge musical influence of mine, Jamey Robinson won a US$50k Pew Fellowship in 2007 for his musical compositions, which were based on playing Bach compositions on a modified keyboard. He took apart a keyboard and rearranged the keys so that the high and low notes were reversed, then he played the Bach pieces on this reverse keyboard and derived new works from it. This analog “remix” is truly a worthy representative of the digital age, as much as rearrangements by artists such as

Girltalk, who almost indiscriminately uses 100s of samples from other songs as components in his own songs.

(The limits of the word “own” here is up for debate, but I would argue that Girltalk is the owner of his output, regardless of the ownership of the input.)

Of course Bach has long been alive only through what he’s left behind, and interpretations and re-workings of his material are in a different position than are most non-public domain, copyright material. Contemporary remixing practices and the advent of instantaneous and global digital publishing throw a wrench in the development of copyright laws over the centuries.

In a recent interview with Creative Commons’ Creative Director Eric Steuer on WFMU, he spoke about the misaligned understandings of the term “non-commercial” with respect to CC’s licencing.

Talking about the results of a study conducted by CC last year, he noted the discrepancies between creators and those who want to use the material. Close to 80% of all the music released with a CC license is released with a non-commercial clause. On the artist’s side of things, they believe that having a non-commercial license will enable themselves to have control over any commercial aspects.

However, the recent move by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation to stop using non-commercially licensed material illustrates where things get complicated. Their reasoning behind this is to protect themselves from violating copyrights, because CBC’s podcasts can be re-broadcast in a potentially commercial environment.

One relief for the situation is that the CC licenses are non-exclusive, meaning that the holders can work out different licensing agreements for different parties.

In CC’s own words:

Speaking about Lawrence Lessig’s idea of the hybrid economy in relation to the definition of “non-commercial”, Chris Castiglione says:

“Lessig uses a similar definition in Remix to describe a work that can both be licensed commercially and shared freely. In his equation the economies of commerce and sharing can co-exist.”

These kinds of arguments would not be necessary if the recording industry with their monied interests were not so intent on strictly controlling the habits of listeners to fit their mold.

But their reasons for maintaining status quo is understandable, in so far as it is for any traditional mass culture industry, that the business models of the last half-century have served them so well. In line with the Chinese proverb — that the supple bamboo is more apt to survive a storm than the rigid oak tree — the old-school industries in their belief of being so strongly rooted are just perfectly set up to shatter.

(side note: This Masters of Media blog has a non-commercial CC licence, meaning, technically, material from here can’t be used on a site that generates any income, whether through having Google Adsense or selling T-shirts.)