The Exquisite Digital Corpse

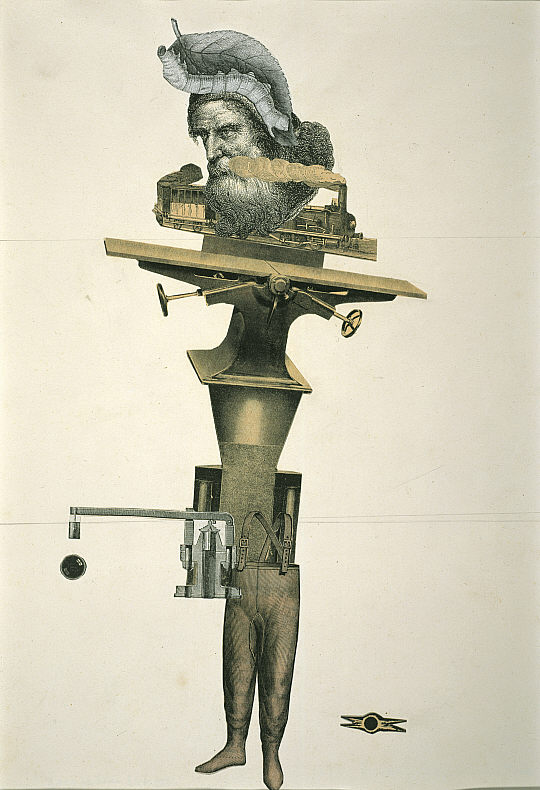

Year: 1925. Place: Rue de Château no. 54, Paris, France. Characters: André Breton, Marcel Duhamel, Jacques Prévert and Yves Tanguy. Plot: A group of surrealists invents a collaborative storytelling technique called cadavre exquis (the Exquisite Corpse) named as such after the first game of that kind, which yielded the sentence: ‘Le cadavre / exquis / boira / le vin / nouveau’ (‘The exquisite corpse will drink the young wine’). To play the game, each participant writes a phrase on a sheet of paper, folds the paper to conceal part of it, and forwards it to the next player for his contribution.

Year: 2010. Place: Theater Kikker, Utrecht, the Netherlands. Characters: Claudia Bernett and you, the modern city dweller. Plot: During the Impakt Festival‘s City as Interface lecture, New York City-based user experience designer and artist Claudia Bernett presents a project commissioned by Impakt and called Tall Tales, which relies on the fact that cities are ‘multi-layered, dynamic, living things in which stories are told everyday literally and metaphorically through the daily interactions of the people living in them’ (1) An old surrealist parlour game called Exquisite Corpse is thus expanded into ‘a collaborative cross-platform, cross-media storytelling experience’ (2).

The paper in the game is replaced by the Twitter interface, the pen turns into the keyboard of a smart phone and the inspiration comes from magnetic tags placed around the town’s landmarks. Entering the URL found on the magnet or scanning the respective code presents the user with the last submitted part of the story and once his own contribution is added, the rest of the tale reveals itself. The artistic potential of Twitter becomes apparent, transforming the microblogging platform into a storytelling medium very different from its broadcast-like status, which I described in a previous post.

This is not the first project of its kind. Bronx Rhymes (2008), authored by the same Bernett in collaboration with Maria Ioveva, dealt with the the history and meaning of hip hop in the Bronx (arguably the birth place of the genre) by tagging historical locations (such as music venues) with posters describing the historical importance of that location with a rhyme and inviting passerbys to join in a rhyming battle by texting their own lyrical compositions. The aggregating website then displayed the artists and locations along with all the submitted rhymes, putting the latest entry on top.

What distinguishes Bronx Rhymes from Tall Tales is how contributions are made: the SMS versus the tweet. While their lengths might be similar (the text message has 160 characters while the tweet cuts things down to 140), the two practices differ significantly in terms of the pointing out authorship. Tweeting parts of story means that the finished publication product contains links to the profiles of those who contributed, thus clearly indicating the digital identities of those involved in the game. Authorship becomes essential for matters of copyright and ownership of content, but in such a small scale, yet growing field these matters are still blurry. If a previous submission inspires the next one, then is the contribution of the person who wraps up the story the most or least original? Whose efforts can be acknowledged as most substantial?

Tall Tales is a prime example of locative media through which creativity is enhanced and simultaneously conditioned by mapping and devices that are becoming widely accessible: ‘the fundamental manifestations of locative media—maps—and the typical site—the handheld PDA—are ubiquitous and easily understood’ (Tuters and Varnelis, 2006). Perhaps the most relevant aspect of these digital publishing projects like the aforementioned ones is how the materiality and content of collaborative storytelling part is affected by geo-tagging, mapping urban environments and the interfaces of social media tools. These little stories should be understood as results of augmented reality physical experiences, in which spaces have tags with existing information in the form of previous contributions, which are later mapped and aggregated.