Blood in our mobiles

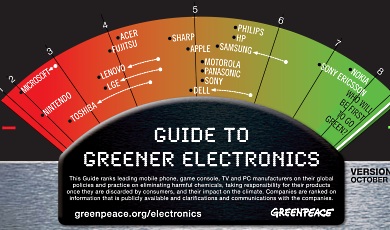

Last week Greenpeace published its revised ranking list of how ‘green’ manufacturers of electronics are. It ranks the companies on their global policies and practice on eliminating harmful chemicals and for taking responsibility of their products once the consumers throw them away. Nokia leads the ranking, and can be considered the most ‘green’ manufacturer of electronics, followed by Sony Ericsson; it seems that like always the Scandinavians are the most advanced when it comes to environmental sustainability.

Last week Greenpeace published its revised ranking list of how ‘green’ manufacturers of electronics are. It ranks the companies on their global policies and practice on eliminating harmful chemicals and for taking responsibility of their products once the consumers throw them away. Nokia leads the ranking, and can be considered the most ‘green’ manufacturer of electronics, followed by Sony Ericsson; it seems that like always the Scandinavians are the most advanced when it comes to environmental sustainability.

The last decade environmental conscious thinking has been high on the agenda, especially in the world of corporations, and for a good reason that needs no further explanation. Next to the environment there has been another change in the acting of corporations; corporate social responsibility.

In light of this awareness, the Dutch television station VARA aired an episode last week of ‘Uitgesproken’ – an in-depth news program – that was about blood mobiles (episode below, sorry only in Dutch). Raw materials, like tin, gold and coltan, which are used in our mobile phones, are being produced in mines in eastern Congo, where pain and suffering surrounds these working places. The rebels and Congolese army have been fighting for years now, at the cost of the Congolese people. The mining industry is being used as one of the biggest funders of this war, which leads to horrific practices. Young children are working in miserable conditions, and people literally die to make our mobiles.

A couple of years ago the word blood diamond dominated our society, which even led to a Hollywood production with Leonardo DiCaprio called Blood Diamond. Because diamonds are a rare commodity, we as consumers could not do much about it. Mobile phones however are massively owned all over the world, and here in Western Europe people even tend to buy a new one almost every year. But nobody seems to be looking for that ‘no blood in this mobile’ label, that’s because there is none.

According to SOMO, a non-profit organization that looks at the consequences of the policy and practices of multinational organizations, the manufacturers of mobile phones are perfectly aware of the fact that they use these ‘blood’ materials. Because of competitive business operations they do not change the situation, but more important, nothing is done because there is no pressure from the politics or the consumer.

The documentary Blood in the Mobile, which can be seen at the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam next month, gives us footage of the mines in Eastern Congo, but also confronts one of the mobile phone manufacturers; Nokia, the company that is ranked highest on the Greenpeace list. The company says that they want to do something about the situation, but that they can’t do anything about it at the moment.

It is true that the production lines of the raw materials are highly complex and it is sometimes hard to know where the materials came from, but as long as governments don’t make strict policy and ‘blood free’ certificates aren’t made, the manufacturers aren’t likely to change their business.

For us consumers it’s impossible to choose a ‘blood free’ mobile but there are a couple of simple things you can do:

– Try not to buy a new mobile every year. Of course the iPhone 4 is faster than the 3GS, and you have FaceTime on it, but just wait one more year, there will probably even be a better phone on the market by then.

– If you are throwing out your old mobile, think of a way to recycle it. Give it to your little niece, or look on the Internet for other ways of recycling. For instance the recycling program of Eeko, a Dutch organization that collects used mobile phones and recycles them.

Or you could just spread the word. The situation hasn’t changed mostly because the consumers don’t complain, most people don’t even know about its existence. So blog, tweet, and write on your Facebook that you are mad as hell, and you’re not going to take this anymore.