Augmented reality: the first steps to a society of control?

Layla van Daalen, Chris Hoogeveen, Hanneke Mertens

Every aspect of the world has an extra layer of information. It may not always be obvious, but these extra layers are most certainly present. Marc Tuters and Kazys Varnelis describe these extra layers as a form of augmented space. This is an extra layer of information, of data visualization on top of what we actually can perceive. New media artists try to play with the boundaries of actual and virtual space. They then try to map it and often display their findings through data visualization. This all sounds very utopic, but is this actually true?

It seems that the interference of the capitalist society may have a negative effect on this form of critical media art. It may become the capitalist apocalypse. Who will use the data and for what purpose? Is it save to participate in augmented spaces? Should we share our feelings or location with other people or should be protect these personal data as good as we can? Or are we getting all worked up for nothing and is the capitalistic apocalypse just paranoid idea? In order to explore these questions certain art works will be discussed to see if there is need to fear augmented spaces and locative media.

There are different ways to experience the aspects of mapping, data visualization and augmented reality within every day life. One of the most commonly known and oldest examples is Carnivore, a net art project by Alexander Galloway.

The software is based one the Carnivore software of the FBI, which was specially designed to intercept and screen specific e-mails. If the software is connected to some point in a network it intercepts all data going through it.

By itself it doesn’t make art and it only offers a small fraction of the capabilities of its commercial counterparts as Lev Manovich writes in Data visualization as New Abstraction and as Anti-Sublime. Instead it offers an open architecture that allows other artists to write their own visualization clients that display the intercepted data in a variety of different ways. This mapping and displaying of the intercepted data is the exact goal of the project of Galloway.

Networked Boxes, is a CarnivorePE Client and was designed by Rizome.org. This client listens to wireless network activity and extracts the IP address and port number from each data packet transfer. In order to keep it simple: visually, every box represents a transfer. The port number defines the color of each box.

According to Mark Tuters augmented reality is either about aesthetics or about interactivity. Carnivore is just new media art; it is all about data visualization. Another project where aesthetics are central is: This is What Wi-Fi Really Looks Like, a project from Arnal, Knutsen and Martinussen.

This artwork tries to show what technologies really look like. The video shows how a staff lights up the signal of WI-FI, and reveals the network. On the site of Gizmodo you can read more about this artwork.

Opposed to the previous two, the Urban Augmented architecture is more about gaming and interactivity. According to the Headmap Manifesto of ‘The new concept of augmented space will offer opportunities for redefining the boundaries of architecture.’ (Russel, 1999:17) The project shows how the artist plays with the boundaries of augmented space and architecture. The possibilities seem unlimited, however, they are rather utopic and unrealistic. The project was part of the Architecture thesis project in Ecole Spéciale d’Architecture Paris Oct 2005 by Quck Zhong Yi, with help from Alexandre Pachiaudi (Pico), Anny Galanou, Gaetan Kohler, Nicolas Trouillard, and Leila.

Another great example of Augmented spaces is the ‘Bijlmer Euro’ which has many similarities with Esther’s MILK project. In the project MILK, GPS-technology is used to map and visualize the global flow of milk from Latvia to the Netherlands. In this multimedia project it is about “Europe as Europe. No borders, just land with people and things. People and things that move” (Milkproject.net)

Very similar is the the work of Christian Nold, known for the Artwork Crowd Compiler, that want us to help understand the movement of all the individuals in one place over time simultaneously. In the project Bijlmer Euro, he worked together with The Waag Society to help us understand the movement of local money in the Bijlmer: a multicultural environment in Amsterdam. The artwork also can be seen in the words of Nold, Deep Social Design. The identity of Bijlmer, and the connection between identity and money is illustrated in this artwork. They wanted to make a currency that ads local value of this currency on the top. In the next video Christian Nold gives a short explanation about the Bijlmer Euro and what they did.

The exhibition of this project is closed now, but a data visualization of the project is still available on their website. This money data visualization will enable local people and shopkeepers to see how money is moving in their local area.

According to the website and what Nold explain as Deep social Design the following is important:

‘Fundamentally the visualization allows anyone to identify purchasing and movement patterns, making it possible to draw conclusions about the use of the currency and the benefits for the local shops’ (Bijlmereuro.net)

In the work of the different authors, the sublime of data visualization is to represent human subjectivity, immersed in data. And that this can represent our experience in new ways. The creators of the Bijlmer Euro hope that “the visualization will contribute to the feeling of being connected to a rich and complex Bijlmer network of culture, economics and people.”

Another project where data visualization is one the key aspects is We Feel Fine. Jonathan Harris and Sep Kamvar created this project in 2005. The tool behind We feel fine harvests human feelings from a large number of weblogs. The system searches the worlds newly posted blog entries for occurrences of the phrase “I feel” and “I am feeling”. When the tool finds such a phrase, it records the full sentence, and identifies the ‘feeling’ expressed in that sentence. Often the system also extracts the age, gender, and geographical location of the author and saves this data with the sentence. This results in a database of several million human feelings, increasing by 15.00-20.00 new feelings a day. Users can search this database and see how a certain group of people is feeling at a certain moment in time. Each single feeling is represented by a particle, which visualizes the feeling by using colar, size, shape and opacity.

It seems like the software of digital art projects like ‘We Feel Fine’ is constantly watching bloggers. Can they still blog safely or do we have to more cautious with express our feelings? Are these art projects creating some kind of Deleusian society of control where we think we’re are constantly being watched? Don’t we feel comfortable anymore about freedom of speech?

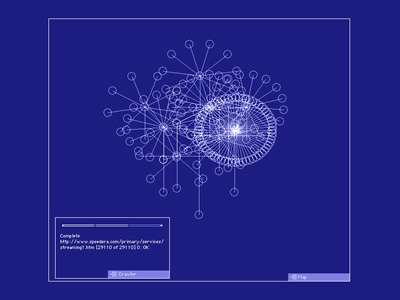

The Webstalker project doesn’t sound as a very safe environment for the Internet user as well. Graham Harwood, Stephen Metcalf, Scanner and Marc Amerika created this project. It is an example of bottom-up development carried out by artists going against the dominant trend. The creative team behind the project promises that it will ‘reshape the internet’ by offering ‘fast and dirty’, ‘high-protein access’ to online media. Webstalker is a browser that imitates the structure of the Internet. When the user types in a WWW-address, the page appears as an HTML-code while the hyperlinks are presented as graphics. The project demonstrates a simple and reduced alternative to Explorer an others, and makes available a mechanism that can be used to investigate the structural depths of the web.

These projects where personal data are being used for creative purposes don’t seem very promising for the common civilian, the common Internet user. Do we have to worry about our personal data being used? According to Marc Tuters it is not like George Orwell described, that we are constantly being watched like in the society of control of Gilles Deleuze. Artists a rather making a game out of it, this way it is fun to participate. For example, Bloggers are rather trying to get their feelings on We Feel Fine, instead of avoiding sentences with ‘feel’ or ‘feeling’.

One final interesting project regarding data visualization is Britglypgh, created by Alfie Dennen. The execution of the project took place from December 2008 till March 2009. He had the idea of using modern technologies to create a Geoglyph and created a platform were people could join to be part of Britglyph. The people, who signed up for participating, were instructed to travel to specific locations across the United Kingdom and bring a stone that they took from their hometown. The Participants used their mobile phones to get the coordinates right. When they arrived at the designated spot, they took a picture or video of themselves and the rock and uploaded it to the Britglyph website. On the 11th of March 2009 the final rock was added and video was uploaded. After all the media was added to the website, the image of a watch and chain was drawn and the rocks creating a Geoglyph in the physical world. Here on the website we can see the image of the watch and chain on the map of the United Kingdom. Britglyph won the Experimental and Innovation Award at the Webbys 2009.

These are all quite familiar and straightforward examples, but there is a more ways to look at augmented reality and data visualisation. This is best illustrated with the example of Uluru. This is a large sandstone rock formation in Australia. Not every space or object is considered a part of an augmented reality. It is sometimes not even considered art. But some features of nature or our cultures should most certainly be considered augmented space, although they don’t look like one in the first place. Uluru is one of those places.

As Russel writes in the Headmap Manifesto: ‘Many Europeans have spoken of the uniformity and featurelessness of the Australian landscape. The Aborigines, however, see the landscape in a totally different way. Every feature of the landscape is known and has a meaning – they then perceive differences, which Europeans cannot see. The differences may be in terms of detail or in terms of a magical or invisible landscape.’ (Russell, 1999:9) From this perspective Uluru is an augmented space; it has features, which cannot be perceived with the naked eye. Every aspect, every feature of it is linked to a significant myth and the mythological beings who created it. These extra layers make it as augmented as any other object discussed before.

Ben Russell refers to the rock formation as Ayer’s Rock, but there is a lot of controversy surrounding this name. In the 1870s Europeans invaded Uluru and renamed it Ayer’s Rock. They explored the territory of the Aborigines with the aim of establishing the possibilities of the area for pastoralism. Also tourists found their way to leave their marks in this sacred place: lovers carved their names in stone and vandals sprayed graffiti on the rock formation.

After more than a century of desecration the Australian Government returned the property to its rightful owners in 1985, the Aborigines. They made an agreement that they could these the area for only 99 years and it would be jointly managed. Since the use of Ayer’s Rock is frowned upon. With all these layers, the tourist layer, the lovers layer, the pastoral layer, Uluru can be considered an augmented space in many different ways

Augmented reality may not be the next big thing. For instance, Layer made itself completely useless. It has no additional value to a map. However, there are still actors creating augmented realities and not just for artistic or utopian purposes. The Waag Society created the 7Scenes application for iPhone and Android Phones. With this app you can experience the city in new ways. You can walk through the city, use your GPS and the application provides you with information about the location where you are.

The project Can Sou See Me Now can be related to 7Scenes, even though it is less spectacular. This work is from the artist group Blast theory. Explained on their website as ‘an artist group using interactive media, creating groundbreaking new forms of performance and interactive art that mixes audiences across the internet, live performance and digital broadcasting’ (Blasttheory.co.uk) In different projects they used location-based devices to coordinate interactions of audience and performers in real and virtual space. In this short video people and things become connected and move. These projects play with the experience of real and virtual space and how the boundaries of the spaces are fading.

Augmented reality and locative media within critical media art may not be the capitalist apocalypse society or not the next big thing, but we need to beware of what the consequences are. We need to be aware of what happens to the information we share to these unknown actors. What happens if we share our location using GPS? Do we want others to know our feelings? One needs to ask these questions before participation in the spaces.

As Tuters argued it will not become a place of control. This form of media art doesn’t strive towards a Orwellian world. Projects like We Feel Fine, BritGlyph and Carnivore are just about data visualization and mapping. These are just pieces of art, however, if the capitalist society interferes we need to be more cautious about what the goals of these projects are.

It seems bloggers, Internet users; participant – we – don’t have to worry too much about what happens to “our” data. Augmented spaces are on the one hand not that successful according as Marc Tuters argued at the Critical Media Art Seminar about mapping on March 10, 2011. This way augmented reality is what virtual reality was in the eighties. On the other hand, it is just are and as an object of study it remains interesting. The new media art scene continues to supply artists with great possibilities. Probably in twenty years we will look at augmented reality as we look at virtual reality today.