Visualizing Academic Interest

The internet has been heralded and praised for bringing democracy. It is stated since the advent of the internet that knowledge is no longer bound to limitations, as it goes freely over the web disseminating to all possible directions. It is what we can learn from each other where we all supposedly benefit from. It’s the so called ‘wisdom of the crowds’, termed by James Surowiecki, that is bringing everyone’s revelation as people in a group are better able to make the best choices than individuals separately are capable of. It‘s the process of ‘information aggregation’ by groups of people that is responsible for better choices and decisions being made for the most difficult issues to be addressed.

Arguably this process is present within the scientific community which is continuously working on and with ideas, concepts and theories of fellow members. Continuously drawing further on preceding scholarly work, filling research gaps with knowledge, endlessly raising new questions illustrating knowledge gaps that will be addressed accordingly to the process described. The process of knowledge production is a process of aggregation; combining ideas, analyzing phenomenon from multiple perspectives, drawing on precedent work with new research methods, addressing questions raised by earlier research, etc etc. All this is done with the purpose ultimately, to learn a little bit more about the world we live in and at the same time constructing that world by the same means.

The democratizing force of the internet described above is contested from many different perspectives. The assumption is countered by the notion of the ‘digital divide’; the gap between people who can effectively access the internet and the groups who supposedly does not. Others state that the digital divide is just a temporal matter because of the simplification of computers and the lowering of costs of information technology, and therefore, by means of market forces, the ‘problem’ of the ‘digital divide’ seems to be eliminated through time. (Compaine, 2001) The latter is ultimately good news as even more people will benefit more from the access to knowledge because knowledge and technological capacity are the forces driving organizations and ultimately countries developments. (Castells, 2005) The ‘knowledge economy’ is greatly enhanced by new media and ICTs which accelerates production of new knowledge. (David & Foray 2002) By promoting access to existing knowledge through networks and facilitating interaction between multiple actors such as designers, producers and users, the speed with which new knowledge disseminates into the public domain is enormously increased. (2002)

This blogpost will not be in the first place about the digital divide, instead it questions the improvement in knowledge production and dissemination by the scientific community with the advent of the world wide web. With the presence of a global information network it seems logic that the proliferation of ideas and concepts will contribute to a more global and intensified collaboration in the scientific community especially because this knowledge is shared easily. Much expected is therefore that the scientific community is more intensely than ever collaborating in finding answers and solutions for the most pressing problems that humanity faces today; aids, malaria viruses, famine, global climate change etc, etc.

Indeed, the scientific community has always been internationally oriented, if not global. Scholars already interacted with each other through journals, publications, seminars and academic associations. (Castells, 2005) Though, according to Castells, network technology helped the scientific community to operate more global, there is still a bias favoring Western and European university institutions, with ‘overwhelmingly dominant access to scientific publications, research funds and prestigious appointments.’ (Castells, 2005) Also, Castells concludes that problems which are critical for developing countries are of little interest to the dominant Western oriented science community. This is shown by the limited sources that are dedicated in finding a malaria vaccine that could save the lives of millions of people. The same is true for AIDS medicines who are being developed in the West but are too expensive for African people, ‘while about 95 percent of HIV cases are in the developing world.’(Castells, 2005) So, it seems that predominantly the issues that concerns Western countries are of most interest of these countries or Western based multinational pharmaceutical companies in the examples given. Indeed, Castells states that the companies business strategies ‘have repeatedly blocked attempts to produce some of these drugs cheaply, or to find alternative drugs, as they control the patents on which most research is based.’(Castells, 2005) So, it can be said that science is a global enterprise but not without exclusion of people who’s urgent problems are not being treated which would lead to an improvement of their lives.

Visualizing from historical perspective

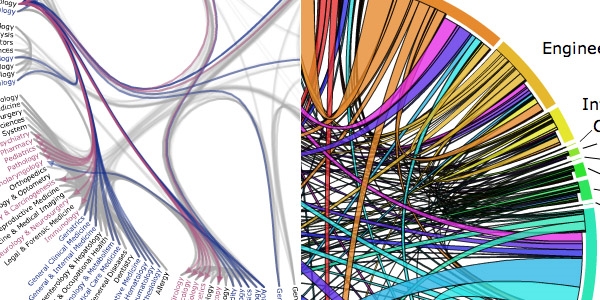

Instead of analyzing literature to come to these findings described by the authors cited, it is also possible to conduct research on the scientific communities by analyzing and mapping or visualizing the interrelations of scientific articles and journals. More specifically it is possible to map the citations between texts and visualize this in a network- or geographical map. Relations between different scientific disciplines can be shown in a comprehensive and easy way, showing, for instance, a scientific ‘standard work’ within a scientific discipline suggested by the numerous times this particular work has being cited by other scholars.

fig1.0 Science Metrix Inc ´relations between scientific disciplines visualized´

The research group of the author is especially interested in visualizing academic trends and emerging and disappearing scientific disciplines.

From a more traditional philosophical perspective the academic disciplines are simply particular branches of knowledge and taken together they form the whole or unity of knowledge that has been created by the scientific endeavor.

In the project the author’s team intends to look at the evolution and discontinuity of academic disciplines from a historical perspective. Historians do this by looking at the specific historical conditions that were responsible for the forming of an academic discipline. (Krishnan, 2009) The research team looks from the inside out; when did the first academic articles emerged concerning ‘terrorism’, which discipline took up this topic and is there a specialized discipline formed for this particular topic with its own methodology of doing research?

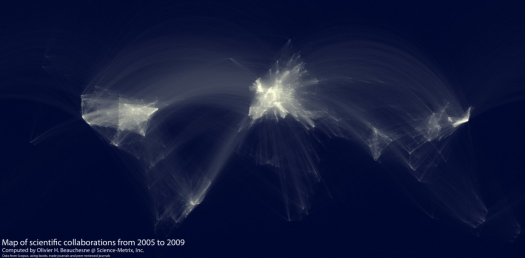

In this way there is more insight in the continuity or discontinuity of specific academic disciplines or even a departure from ‘obsolete’ practices and/ or a way of thinking about a particular problem. Also, by locating this academic work on a geographical map it is instantly clear which countries take the most responsibility for the research on a particular issue.

The importance of analysis and visualization tool of the research group lies in the coupling of the interest of emerging or known academic disciplines with ‘human rights issues’ which are defined by the United Nations. In this manner the project is determining the emergence and the collaboration between different academic disciplines and also the period of the upcoming interests of academic scholars for particular global societal issues. As Krishnan contends, in the late 19th and early 20th century many academic disciplines emerged because of the need for disciplines that particularly dealt with a particular object or topic that was not covered by another discipline ‘An anthropologist was concerned with culture, by which he meant not literature or the fine arts but primarily group attitudes, frequently focusing on pre-literate societies.´ (Krishnan, 2009) The purpose for this strict division between disciplines was mainly because it allowed for a strict set of research topics and a stable research agenda for research and further development. In the present time disciplines are now more identified by the methodology they apply to certain topics or research fields rather than through the topics or research fields themselves. (Krishnan, 2009) By projecting the network graph on a topographical map it is clear which countries contribute in knowledge production for a particular UN human rights issue and what the strengths of collaborations are between countries per issue.

fig 2.0 Science-Metrix Inc ´global map of scientific collaborations´ by Olivier H. Beauchesne

Insights

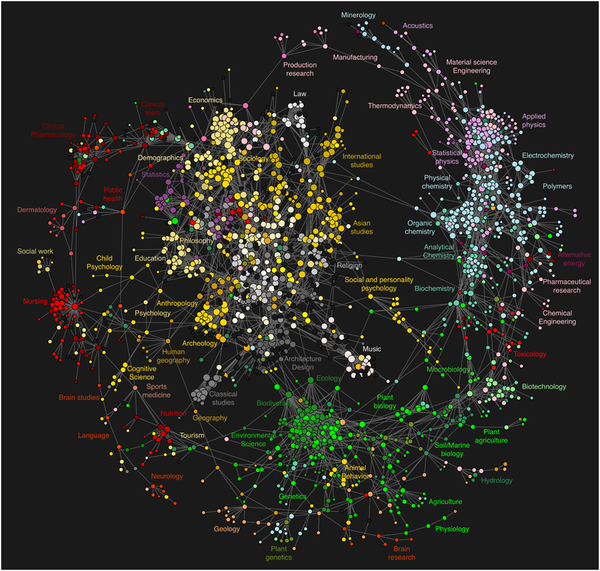

This way of historical analysis gives us the opportunity to give an insight in the new disciplines that emerged to meet particular political and societal needs. The analysis tools can give an insight in the way the issues are dealt with. What does the interest of a particular academic discipline say about the possible and intended solutions for a particular issue? What can be said about this ‘academic discipline specific’ way to problem solving? The project group believes in this way it is possible to research critically what the implications are between the differences of the academic disciplines in addressing these issues ‘What underlying motivation is accompanied with the methodology of the discipline?´, ´Who’s problems are being solved here?´, ‘Whose interest is served best with the attention of this specific academic discipline?, The people in trouble or the authorities profiting on generating knowledge?” Other questions that need to be addressed are more concerned with the way of analyzing the mass of scholarly work. Is, for instance, the search for particular topics mentioned in the abstract of academic journals and articles a reliable way of categorization? Or, is the measurement of the citations of articles a representative way of doing research in getting insight in which articles are most read and used for further academic work? The picture underneath is a comparable project but with a different strategy of analysis. Instead of looking at the amount of citations of articles the Los Alamos team looks at the interest in articles by analyzing the actual usage by scholars of the articles in multiple academic databases. The team argues their strategy is superior to citation analysis as they capture the interest in article that are not widely cited but are widely read.

fig 3.0 The Alamos Team ´Map showing connections between scientific disciplines´

References:

Compaine, B. (2001) ‘Re-Examining the Digital Divide’ The Digital Divide: Facing a Crisis or Creating a Myth Benjamin Compaine, Editor MIT Press Forthcoming 2001

Castells, M. (2005) ‘ The Rise of the Network Society’ In: ‘The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture’ Volume I, Blackwell Publishing

Surowiecki, J. (2004) ´The Wisdom of Crowds: Why the Many Are Smarter Than the Few and How Collective Wisdom Shapes Business, Economies, Societies and Nations´ Little, Brown

Krishnan, A. (2009) ‘What are Academic Disciplines? Some observations on the Disciplinarity vs. Interdisciplinarity debate’ University of Southampton, ESRC National Centre for Research Methods, NCRM Working paper Series

David, P. Dominique Foray (2002) ‘An introduction to the Economy of the Knowledge Society’, International Social Science Journal 171: 9-23