Book Review: Alternative and Activist New Media by Leah Lievrouw

Drawing on the works of David Bolter and Richard Grusin and their seminal work – “Remediation: Understanding New Media”, Leah Lievrouw analyses in ‘Alternative and Activist New Media’ (Polity Press, 2011) a series of new media activism practices. Offering a wide set of study cases and examples of such practices she concludes that the digital cultures context is undergoing a cultural shift from mere broadcasting to mediation.

“The events of our mediated culture are constituted by combinations of subjects, media, and objects, which do not exist in their segregated form. Thus, there is nothing prior to or outside the act of mediation”. (Bolter & Grusin, 1999, p.58)

Lievrouw sees mediation (understood in its both senses: use of technological channels to extend or enhance communications and also the interpersonal process of participation in the creation and sharing of meaning) as an on-going, mutually shaping relationship between two models of communicative action she calls reconfiguration and remediation. The first represents the uses of media communication technologies, namely their adaptation by users to best fit their needs, in a constant process that also keep new media ‘new’. The second stands for the remediation of communicative action at all levels of content, form, and structure, expressed in the remixing of existing materials, expression, and interaction, thus creating innovative works and ideas by participating in the creation of shared new meanings. This is a process that continually produces social change.

Adding to the theory of Bolter and Grusin, remediation is not seen here as just “the presentation of one medium in another” (Bolter & Grusin, 1999, p45), but also including among: repackaging, enhancement, refashioning, and absorption practices like: mobilization and integration, prophecy and hack.

“[Mediation] provides a new and potentially powerful way to think about the interdependences and mutual shaping of communicative action and communicative technology in society more generally. The key point is that people’s expressions and interactions are inseparable from the devices and methods they use to create, sustain, or change them. This relationship is a moving target, or perhaps more accurately a moving window, for viewing communication as the fundamental mechanism of social change.”

Interested in investigating the contending views of what she calls the competing pipeline (the mainstream center, the dominant cultural discourse) VS the frontier vision (participatory fringe new media projects), Lievrouw focuses on the features of the fringe activities of digital activism. She places them in a strict theoretical framework across 5 genres of such collaborative activities: culture-jamming, alternative computing, participatory journalism, mediated mobilization, and commons knowledge. After surveying these new media projects the author concludes that these genres are good indicators of how mediation influences culture change by ‘pushing’ it in different directions.

The 5 genres have three basic common features, among which they very in content:

- Scope or size: derived from the small-scale and collaborative character of alternative projects

- Stance: determined by the relation with the mainstream – can be ironic, subcultural or heterotopic (outsider)

- Potential for agency or action – interventionist (lead to direct action) or perishable (temporary)

Thus, Lievrouw establishes in the second chapter a framework on which she filters all the examples offered to illustrate the 5 genres throughout chapter 3 to 7.

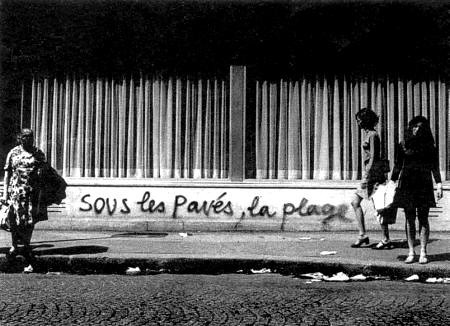

Lievrouw traces the sources of present activist new media practices and movements in the social and artistic currents of activist art, namely the DADA movement (contemporary to the First World War) and the Situationst International associated with the French social movement of 1968. These are, Lievrouw argues, artistic moves with explicit political objective, critique of political and economic regimes, and that make use of popular media technologies & content to intervene in mainstream culture, mixing media in order to manifest.

- Graffiti made during the May ’68 movement that reads: “the beach is under the pave stones”, reference to the street pave stones thrown by students at the police.

Another root for digital activist studies is placed in social movement studies, particularly in the emergence of new social movement theories of Touraine and Melluci and the related perspective on collective action. These theories are the first to make the transition from the society wide, ideologically driven movements of the industrial age to smaller scale movements focused on wide ranging issues (ecology, anti-globalization, anti-nuclear), but also on group identity and lifestyle issues (gay, women rights, national identity) that arose in the 1960 – 1980s period.

Probably the most spectacular of the 5 genres of digital activism is culture jamming. Done both on and offline, it borrows from, comments and fights against popular or corporate culture (entertainment, advertising, arts) through guerrilla or viral practices in order to subvert these cultures. In this case Lievrouw offers a series of edifying examples for offline (The Surveillance Camera Players who perform classical plays to CCTV for who ever is watching) but also online culture jamming (like Jonah Paretti’s Nike Media Adventure – a widely-forwarded email thread between Peretti and Nike after the company refused to print the word “sweatshop” on Peretti’s custom Nike iD sneakers). The author offers as base case study the ®™ark’s group – the “corporation” designed to critique consumerism and corporate culture, that brings together artists and funders. ®™ark is said to be responsible for such activist acts as FloodNet, the www.gwbush.com spoof website or the Dow Chemical Company parody website of the Yes Men.

Alternative computing is used to describe the practice of hackers and hacking to expose institutional or corporate wrongdoing through the hack and redesign of the IT, but also integrates such concepts as open source, file sharing or hacktivism. The study case in this chapter focuses on the legal actions taken by the entertainment industry in order to prevent Hacker Quarterly to publish the DeCCS code that enabled users to decrypt content of DVD videos, followed by a global support movement towards the magazine.

Covering the subjects or points of view that are neglected by mainstream media is the main practices of participatory journalism. Seen as a reaction to the marginalization or exclusion of local content, participatory journalism is thought to be a partial solution of the press crisis. Indymedia or Independent Media Center newswires are the most important grass-roots journalism open projects online since their launch in Seattle, previous to the 1999 World Trade Organisation meeting, when they were meant to cover the wide range of protests at that time.

Mediated mobilization is described as being the use of social networks to mobilize and coordinate people into engaging in live and mediated collective action, but also to use social media as a space of action in itself where activists produce and distribute content. The most suitable example, Lievrouw argues, is the global justice movement. Credited also to the Indymedia movement associated with the 1999 WTO meeting, it fights against globalization and social inequity through the use of the power of local and live social relations activated through online communicative action.

Finally, Lievrouw also touches on the genre of commons knowledge by using the modern time “Alexandrian Ideal” – Wikipedia. Through this example she demonstrates how this vast alternative new media project has opened the way for grass-roots alternatives that make use of bottoms-up methods like peer production and collect, organize, classify and evaluate information in systems that challenge expert consensus. Wikipedia’s evolution is seen as closely linked with 2.0, namely the transition from collaboration to crowdsourcing and the development of search engines and tagging.

Lievrouw argues that the alternative and activist media surveyed provide strong empirical support for a mediation theoretical perspective on the communication processes.

By framing the 5 genres in a complex theoretical system, based on their features, the author gives at least a complex description of the hallmarks in the today’s new media activist and alternative scene. At the same time, giving the constant ‘new’ factor that keep new media differentiated from traditional ones, the examples tend to be somewhat out-dated, at least considering the mediated mobilization that played a particular role in the “Arab Spring” and that could also make an interesting case. I also felt there is still room for a clear theoretical bridge between the alternative genres and the mediation theoretical framework of social change through reconfiguration and remediation, but still, it is a valuable reading for anyone interested in the new media’s powers to challenge the ‘the system’.

References:

- Bolter, J. David, and Richard Grusin, aut. 1999. Remediation: Understanding New Media. Mit Pr.

- Lievrouw, Leah, aut. 2011. Alternative and Activist New Media. 1 ed. Polity.