Book Review: opaque presence: manual of latent invisibilities ed. Andreas Broeckmann and knowbotic research

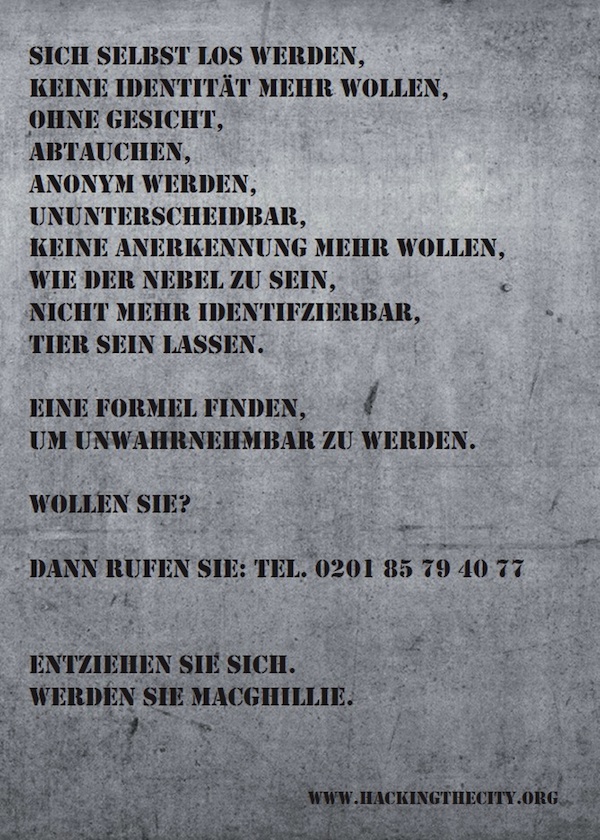

opaque presence instructs toward a mythology of suspended origin. Such a creation myth is necessarily one of destruction. Fully actualized, opaque presence could deposit the naked and the clothed in the Garden of Eden as a garden, an unbroken sanctuary, not a place, but a nothingness. However, the world turns more like a city. opaque presence calls for the refutation of centrifugal home in the ego. It calls for a limbo, indeed, a “latent invisibility.” It calls for nomadism as a state of consistency, a form of rest in the subjugation of:

seeing vs. perception

identity vs. anonymity

authenticity vs. repetition

empiricism vs. occult

time vs. temporality

nothingness vs. negation

mobility vs. latency

opaqueness vs. invisibility

opaque presence calls for two sides of the same coin that, in the absence of gravitational pull, will spin forever—two sides that contributing writers knowbotic research term “here, not here,” Eva Meyer terms “no longer and not yet” and Andreas Broeckmann terms “passing by.” opaque presence invokes Heidegger’s Dasein—the eye of the storm brewing between opposing totems—the fulcrum of a totemic range turned horizontal like a seesaw. “Dasein always understands itself in terms of its existence—in terms of a possibility of itself: to be itself or not to be itself,” Heidegger writes. “’Dasein’ has either chosen these possibilities itself, or got itself into them, or grown up in them already,” (33).

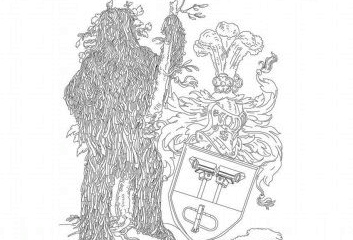

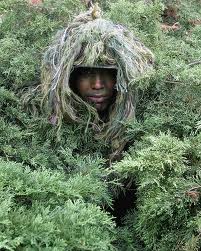

The self-sufficiency of Dasein, however, requires movement over time. As a book, opaque presence instantiates rhizomatic movement over a terrain of contributing writers (including the artist collective knowbotic research, the journal Tiqqun, Eva Meyer, Matthew Fuller, Andreas Broeckmann and Marcus Steinweg); editors Broeckmann and knowbotic; and publishers diaphanes and its imprint, les jardins des pilotes (an initiative of Broeckmann and Stefan Riekeles). opaque presence demonstrates the act of reading, artistic advancement of content and embodiment of physical mobility through overarching reference to a extra-diegetic project by knowbotic titled macghillie – just a void that provides the opportunity to don a ghillie suit—designed for hunting in nineteenth-century England, employed prominently during WWII and mined for contemporary disruptive pattern camouflage—to any responder partial to experiencing contemporary, cosmopolitan society with an anonymity engendered by both the subtlety and brazenness of the act:

macghillie occurs around Zurich. Without goal, without intention, without purpose it pervades the city. Not only is there complete uncertainty of what it’s doing here, but also of what it is. Not man, not woman, not old, not young, neither forbidding nor cutesy. macghillie eludes every categorization. It is possible to say what it is not, but difficult to determine what it is. How long can it do well in a city in which everything is classified and optimized? Is there space for something that wants to be nothing? (knowbotic research; trans. from the German mine)

Although the mac-ghillies—in the collective personification of one MacGhillie— loll silently forward, a sasquatch navigating its way with benign absurdity through Zurich like a cat trussed up in winter booties and sent out into the snow, opaque presence carries a military (albeit not militant) omnipresence that posits space for nothingness as a battle worth fighting. This desire propels MacGhillie against the book’s photographic backdrop, depictions of camouflage tactics that may exist in the archives of distant insurgencies on faraway continents in unfamiliar climates, in the reader’s contemporaneous perception and/or the lukewarm gray of memories cast by its shadow.

Although the mac-ghillies—in the collective personification of one MacGhillie— loll silently forward, a sasquatch navigating its way with benign absurdity through Zurich like a cat trussed up in winter booties and sent out into the snow, opaque presence carries a military (albeit not militant) omnipresence that posits space for nothingness as a battle worth fighting. This desire propels MacGhillie against the book’s photographic backdrop, depictions of camouflage tactics that may exist in the archives of distant insurgencies on faraway continents in unfamiliar climates, in the reader’s contemporaneous perception and/or the lukewarm gray of memories cast by its shadow.

MacGhillie’s propulsion is documented by photographs that either accompany the text or photographic interludes that urge it pause, as if MacGhillie was stopped at a crosswalk,

Sierra Tango Oscar Papa, significant yet nonsensical next to a woman in a sweater and scarf. However, photographs juxtapose MacGhillie against modes of transportation (train platform, highway, airplane), states of transparency (window, construction site, tall staircase) and spaces of indeterminate urbanism (thick fog, golf course, silty field) more commonly than people. MacGhillie’s propulsion also matches stride with a guerrilla dictionary of annotated photographs ordered alphabetically and appearing strategically in the margins. The most belabored entry, roaming around, unravels into a kind of poem, a motion unto itself, that closes with the following words also excerpted, obliged toward line breaks and dispatched to the back cover:

in a fleshless shell

the messianic animal

again, not

The Five Obstructions: A Companion Manual

I found myself walking with MacGhillie, over sidewalks and perhaps over water, in the company of another manual—one that enabled me to excavate questions of digital culture from opacity—one that governed the making of The Five Obstructions (2003), a documentary film by Lars von Trier about the remaking—five times—of The Perfect Human (1967), a short film by Jørgen Leth, in adherence to restrictions imposed by Von Trier. The Five Obstructions is predicated on the “Vow of Chastity” taken by the filmmaking collective Dogme 95 to refuse the temptations of sets, props, editing, technology and other perceived embellishments in the exercise of adhering to uncompromising truth.

Several of Von Trier’s obstructions forced MacGhillies’ nomadic sentiments upon Leth, requiring him to shoot in Cuba and Belgium what he had perfected for Denmark. The second obstruction required Leth to remake his film in a location deemed insufferable by his own discretion without revealing the location itself. “Leth is well aware of the trap Trier has posed for him – that he make clear his representational authority by speaking explicitly for others,” (Lynes 598). Von Trier urged Leth to “crack up” against the background of his own film, that is to say, his de facto politics, to the effect that Fuller suggests rumors have upon their subjects (38). Von Trier urged Leth to yield ontology between seeing-perception, a friction treated so reverently by opaque presence. The resulting scene culminates in Leth, cast as his own protagonist, consuming an opulent meal separated from the women and girls on the streets of Bombay’s red light district by a transparent screen:

Meyer writes from the oscillating perspectives of herself inside and outside the mac-ghillie. She asks MacGhillie to show her motion as a mode of becoming. “I would like to grasp the difference between the visible and invisible through me, without making it the subject of a representation and subordinating it to identity,” Meyer confesses (15). She desires to be Baudrillard’s graffiti, “… transgressive not because it substitutes another content, another discourse, but simply because it responds, there, on the spot, and breaches the fundamental role of non-response enunciated by all the media,” (287). She desires to be Leth’s foil in Von Trier’s second obstruction.

To camouflage is to bear constant witness, immersed but non-contingent, like the sex workers in Leth’s background. Leth failed the second obstruction by partially revealing his chosen location. “In the society of late capitalism… visibility and transparency are no longer signs of democratic openness, but rather of administrative availability,” (Bueti 148). Transparency, according to Von Trier, constituted a “perversion” worse than the totality of directorial distance that he initially sought to disrupt (Lynes 601). Is MacGhillies perverse in its distance from dominant culture? (What happens when Lynes’ “relay of visuality (subject-director-spectator)” (598) becomes a single marathon?) Is dominant culture perverse in its distance from MacGhillies? Fuller breeches these questions by granting them co-custody of seeing-perception (44). Despite its militaristic imagery, opaque presence is more interested in a gentleman’s dual such as that between Von Trier and Leth than the near-sightedness of war.

Utopia vs.

opaque presence empowers MacGhillie toward a constant comparable to Von Trier’s uncompromising truth. Unlike Von Trier, however, MacGhillie’s aim is not to break but to break from dominant culture. Federica Bueti writes, “Maintaining the performative sway of participation, we constrain collaboration to a mantra that serves the purpose of the already existing apparatuses. Substantial changes, and an altered concept of participation, can only be brought about by a deliberate fracture.” MacGhillies could embody a deliberate fracture reminiscent of Timothy Leary’s call to “Turn on, tune in, drop out.” Will the mac-ghillies legacy outshine the counterculture of the 1960s? The avant-gardes castrated by Tiqqun? On one hand, the photographic elements of opaque presence encourage coming-together through transcendence– freedom through surveillance– nothingness through permeation. MacGhillie poses on the book cover with a coat of arms depicting security cameras.

Distopia vs.

On the other hand, to participate in a cultural system is to be a Perfect Human under surveillance of the kind that observes Claus Nissen and Maiken Algren going about the daily tasks of the bourgeoisie. They exist on the white set of Leth’s film, a carte blanche, and choose their status as Von Trier forced Leth to (re)choose his own. They are formally attired, dressed for the presentation of the self to unknown constituents. MacGhillies throws stones in glass houses—desires the truth—desires, as previously stated, a space for nothingness. MacGhillies cannot help but be a desiring object—not (to reference another filmmaker, Luis Buñuel) an Obscure Object of Desire, but on the contrary, one so ubiquitous as to fade into exceptional freedom. However, as Leth observes:

“Keeping distance is a technique, and I’m aware of its emotional costs. I’m very well aware of that. But I think it’s an illusion to think that there’s a deeper and a more true [sic] source beneath the way I work—a source that can only be reached by breaking down the technique. It’s romantic, and I don’t believe in it,” (BOMB magazine).

Perhaps the dissatisfaction of MacGhillies that I sense in the weak gray, blue and taupe of its photographs lies not in its decision to go rogue, but in the realization that its chosen path requires being the Perfect Mac-Ghillies, an avatar by any other name. Over the course of opaque presence, the mac-ghillies become a symbol, the very nature of which compromises their revolution. According to Baudrillard, “‘Revolutionary’ doctrine has never come to terms with the exchange of signs other than as pragmatically functional use: information, broadcasting, and propaganda,” (279).

In an incarnation of how the medium is the message, Lynes suggests that media not only represent, they consume (606). A documentary film begets implicit messages that Von Trier tried furiously to break by setting five obstructions in a motion echoed by opaque presence. Fuller hitches his bandwagon to their momentum with almost utopic zeal: “The properly ordered predicates of a person loop [or the remaking of a film five times] become a moebius strip, not in their strict order of disappearance but in that the mechanism by which they appear, that of language, manages to bootstrap itself into being, as nothing in the first place,” (41). Again the exaltation of the void!

Von Trier’s chastity, his filmic asceticism, contends Lynes’ observation of “modesty” as that which separates the witness from the Spectacle. Chastity and modesty are as synonymic at first encounter as the democratizing promise of digital culture and MacGhillie’s flaneuristic self-exile. Martina Lauster, however, argues that Benjamin’s flaneurie references the arcade as an other, thereby doing the nineteenth century an injustice and alienating himself in reciprocity. What is the reader to do if MacGhillies and dominate culture cannot help but validate one another? Heidegger writes in “The Age of the World Picture:”

“Everyday opinion sees in the shadow only the lack of light, if not light’s complete denial. In truth, however, the shadow is a manifest, though impenetrable, testimony to the concealed emitting of light. In keeping with this concept of shadow, we experience the incalculable as that which, withdrawn from representation, is nevertheless manifest in whatever is, pointing to Being, which remains concealed,” (153).

Meyer foreshadows this deadly reflexivity in the very first paragraph of opaque presence’s first essay when she describes Diogenes’ opposition to the Eleatics’ denial of motion: “[H]e perceives something present, as if it had been once before, and at the same time makes it present in reverse, in the act of perception itself,” (12). For the fifth and final obstruction, Leth must deliver a monologue directed to and written by Von Trier: “I obstructed you, no matter how much you wanted the opposite,” Leth as Von Trier as Leth laments. “And you fell flat on your face. How does the perfect human fall? This is how the perfect human falls,” (Lynes 609). The Five Obstructions fell from Dasein by yielding to relativism, what Christopher Macann calls the “They”:

“[I]f the ‘They’ is what levels Dasein down, takes Dasein away from itself, then ‘inauthenticity’ would appear to be the inevitable result of being-in. Worse, if Dasein is taken away from itself from the very first, then what sense does it make to talk of Dasein being brought back to itself again—as is required later by the theory of authenticity. Who is it that Dasein comes back to when it comes back to itself if there is no Being-self which pertains to Dasein, prior to falling?” (92-3).

Who is it, then, that Leth’s monologue comes back to?

What is it, then, that MacGhillies comes back to when its motion finally halts?

Bibliography

Baudrillard, Jean. “Requiem for the Media.” The New Media Theory Reader. Ed. Noah Wardrip-Fruin and Nick Monfort, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003 :259-276. Print.

Bueti, Federica. “Give me the time (For an aesthetic of desistance).” art&education Papers. August 2011. Web. 17 Sept. 2011.

The Five Obstructions. Dir. Lars von Trier. 2003. Film.

Heidegger, Martin. “The Age of the World Picture.” Trans. William Lovitt. The Question Concerning Technology and Other Essays. Ed. William Lovitt. New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1977 : 115-154. Print.

—. Being and Time. Trans. John Macquarrie and Edward Robinson. New York: Harper & Row, 1962. Print.

knowbotic research. “macghillie— just a void.” macghillie.krcf.org. knowbotic research, n.d. Wed. 16 September 2001.

Lauster, Martina. “Benjamin’s Myth of the Flaneur.” The Modern Language Review (Jan. 2007). BNET. Web. 15 September 2011.

Leth, Jørgen. “Jørgen Leth by Anne Mette Lundtofte.” BOMB 88 (2004). Web. 15 September 2011.

Lynes, Krista Genevieve. “Perversions of Modesty: Lars von Trier’s The Five Obstructions and ‘The Most Miserable Place on Earth.'” Third Text 24.5 (2010) : 597-610. Academia.edu. Web. 17 September 2011.

Macann, Christopher. Four Phenomenological Philosophers: Husserl, Heiddegger, Sartre, Merleau-Ponty. New York: Routledge, 1993. Print.

The Perfect Human. Dir. Jørgen Leth 1967. Film.