“What are your religious beliefs?” – a question of if religion becomes public again in social networking

Events of April 2011 sparked much controversy as the French government declared the public wearing of niqabs and burqas illegal for the first time. The response to this was defiance by many in France who define themselves as Muslim (and also many who do not), with immediate protests taking to the streets in the capital and beyond. The story progressed this week with the first fines being handed out to those found continuing to wear the burqa in public. One such protestor called her actions as “freely expressing their religious beliefs”. This event displays that within the realms of the largely secular streets of Europe, the enactment of people’s personal religious identity is still vital and is sometimes played out in a very public way.

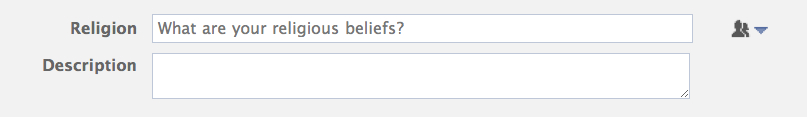

While religious identity is played out on the streets of France, every day, in a small box hidden away in ‘philosophy’, Facebook users are requested to make the decision whether to publicly state their ‘religion’ in their Facebook profile. This is a pertinent question as we live in an age where there is increasing “secularity…in terms of public spaces…(which)…have been allegedly emptied of God, or of any reference to ultimate reality” (Taylor 2007:4). This is interesting as the religion box represents a very public space where people are asked to make a deep and essential decision of how to define their religious and spiritual beliefs.

Debate surrounding the role the spiritual plays in public life within new media forms is far from new. The controversy is rooted in the fears people feel about the shallow and disruptive nature of new technology forms before they are normalised within a society. Enzenberger stated that “The new media are oriented towards action, not contemplation; towards the present, not tradition.” (2003:265). The fast, responsive rather than reflective nature of online discourse has been criticised for not naturally lending itself for many to the deep, spiritual nature of the traditional notion of religious contemplation. This is displayed in debate surrounding the option to receive communion online or the questions surrounding the authenticity of taking a ‘cyberpilgramage’ (Hill-Smith, 2011), succinctly discussed below by Connie Hill-Smith. Indeed, the questions are raised by religious figureheads around the world. Mark Oestricter, an evangelical Christian leader, sees connections online as ‘superficial’, while “unplugging” was seen as a necessary “spiritual journey” for US pastor Anne Jackson.

Peter Berger, a well know Austrian sociologist, claimed in his study The Homeless Mind that modernity has lead to the ‘privatisation’ of religion where ‘religion…has become largely privatised, with its…structure from society as a whole to much smaller groups of confirmatory individuals’ (1973:186). Berger has since claimed that this is not wholly possible, however more recent studies applied to the media have echoed this statement.

“All forms of mass media are theorized to reflect the move toward greater secularization, presenting a predominantly secular image of the world we live within. Subsequently, strong religious affiliation will be negatively related to all forms of mass media use because a vast majority of media content does not reflect traditional religious values” (Armfield & Holbert, 2003:130)

This study was, however, conducted in 2003 and since then there has been a rise of cross-platform religious Internet use as the Internet is ‘normalised’ as a communication tool in society. What I would like to ask is are people using Facebook and social networking platforms to reconnect with ‘society as a whole’ or is religion being left out of this public space and therefore reserved for private, ‘smaller groups’? I feel by studying how the ‘public’ is being enacted, initially looking at the ‘religion’ field and then extending it to specialist, religious social networking, one can draw conclusions about whether the Internet is seeing to be a forum which ‘reflect(s) traditional religious values’.

To do this I want to initially be able to look at if people are openly identifying their ‘religious beliefs’ on their Facebook profile, the central marker of ones identity on the platform. I hope to be able to draw conclusions about the compatibility people see with generic social networking sites and what they see as their most private beliefs. The originality of this research method was to try and use this one aspect of Facebook to tackle larger ideas of the public role the Internet plays in religious communities. I then wish to look at where religion is being enacted in the public realm on Facebook by studying the uptake and use of social pages and whether these are active forums or not. Finally, I wish to investigate what other religious platforms people are using in the social networking realm and whether these are being seen as attractive alternatives as offering the ‘private’ in the ‘public’ realm of the internet.

To begin looking at how it is possible to address studying the ‘religion’ box quantitatively, I attempted to use Gephi to analyse how my 429 Facebook friends have represented themselves in their ‘religion’ field on Facebook. This proved instantly problematic as Gephi could not access this information due to the restrictive privacy settings put in place by Facebook. In response to this I sampled the first 100 Facebook users in my friends list alphabetically, looking at how they respond to the religion field. In this survey I found 75 left the section empty, 12 filled in disruptive answers such as ‘pineapple’ and ‘jedi’, 6 called themselves an ‘Athiest’, amongst the remaining responses only 2 Christians, 1 Catholic and 1 Hindu represented themselves.

This small sample suggests that the enactment of religious identity is not generally considered worthy of such a small, limited and public space and is rather something that should be reserved for more serious, human or face-to-face enactment. It could also be argued that many see it as too personal and should be information only shared with their most intimate of friends. This fits in the model of the UK secular society where religion is generally left to the ‘personal’. It is, however, important to understand the limitations of this small, manual sampling method. The sample is restricted to only my 429 friends, a set of data which is limited in being largely consisting of Facebook users aged between 18 and 27, educated and located mainly in southern England and around Europe (stats gathered using Socialistics Facebook app).The method was also very time consuming and lends itself to human error.

While people in one student’s network reveals little about religious enactment and identity online in a broader sense, studying such a focused element such as the responses in the one ‘religion’ box does offer interesting information on particular social groups in the way that section of society view religion’s compatibility with this public space. In order to be able to draw wider conclusions on people’s reactions in presenting their religion, it is necessary to sample a much larger cross section of society. Due to the global nature of Facebook discourse, it would be desirable to sample from a range of international states. Indeed, in secular Europe, religion is reserved for the private whilst in many countries around the world, religion is tied in much more closely with the state and public life and hence plays out in a much more public way. It would be illuminating to see if this enacts itself online. Indeed, this could be achieved by looking into nationality, age and gender and to study see how these factors influence the use of the religion box. I feel an option would be to use Facebook pages of the major religions such as ‘The Bible’ and ‘ILoveAllah’ to leave questions to its members over their use of the Facebook box.

There has been some previous research of religion on Facebook which may offer some insight into the subject and shows the relevance of studying this aspect of the Facebook profile in more detail. There is indeed no lack of public online discourse surrounding religion on Facebook. Firstly a study in 2009 showed that of the 250 million users on Facebook, 150 million did choose to disclose a ‘religion’ in their profile, contradicting my restrictive sample and showing the worth of sampling the religion box on an international basis. Furthermore, a second, more recent study, has shown that while religious pages on Facebook are not the most populous in users, they do top the global charts in terms of the most interactions happening within a given page on a daily basis. The most pages which contained the most daily interactions between users were ‘Jesus Daily’ and ‘The Bible’, suggesting that serious religious debate and interaction is actually happening on Facebook. This is not restricted to Christian debate, indeed, the page ILoveAllah.com involved over 373 000 interaction in April 2011 and has over 6 000 000 users and a this is a rising number. On these pages, participants, amongst other actions, share photos, make religious statements and discuss videos and media. So this shows that there are many on Facebook who are engaged in their religion and happy to display the debate publicly. This suggests complexity of the way religion is enacted on Facebook, as the Internet is demystified and normalised in society, it becomes a more public space for religious enactment.

To move this study away from the much debated Facebook platform, it is important to study where else religion is being enacted in social networking and what implications this has. Indeed, some see the Facebook platform as lacking the critical and religious focus that is required to enact ones religious identity online and so turn to contained religious focus social networking sites such as Xianz.com. The popularity of such services confirmed through the plethora of options available to people wishing to use social networking within a range of religions. Indeed, the rise of Ikhwanbook.com has been studied by Karim Tartoussieh who sees this Muslim social networking platform set up by the Muslim Brotherhood as being seen by its users as a space away from the ‘Islamaphobic prejudice on the part of the management of Facebook’ and a space for Islam related ‘ideas’ to circulate freely (2011:202). An interesting development of Ikhwanabook was to create a page on Facebook and so interrelating the ‘publicness’ of Facebook with the segmented nature of Ikhwanabook. This begins to ask questions about the sustainability of the ‘publicness’ of Facebook and a study of the uptake of these sites would be useful. If sites such as Ikwhwanabook raise in popularity then it may suggest that the private is being reinacted within the social networking sphere. They are creating ‘individual’ networks, reserved only for those who practice the specific religion. If one was to compare the public enactment of religion on profiles within these closed networks in relation to the trends in profiles on Facebook conclusions could be drawn about the publicness of Facebook as a platform.

An initial study, after setting up a profile on the Ikhwanabook platform, if that there is less emphasis on the ‘personal’ profile. You are not asked to disclose ‘unworthy’ likes and dislikes of films and music, photos are hidden away in a tab at the back of the profile and the emphasis is placed on the ‘shared’ thoughts with a personal blog being set as the first tab. Furthermore, all updates are placed in the shared central platform when you sign in. This shows that the space being created to encourage ‘public’ thoughts and developed discussion rather than ‘private’ inane and shallow conversations. This suggests that maybe instead of viewing that the communication online is in someway naturally ‘impoverished’, it can be structure in such a way to encourage worthy debate. While Guardian writer Mohamed El Dahshan criticises Ikhwanabook and other muslim social network platforms such as Muxlim for relatively low numbers and limited ‘regional’ scope, I ask is he missing the point and indeed is this the future of social networking? Will there be one central ‘general’ network and then many specialist sites offering small moderated ‘villages’ within the global city?

Now that I have displayed, albeit briefly, the complexity of the use of Facebook within religious beliefs, I return to the proposed methodology of the wider investigation. By showing the plethora of users that are actually choosing to leave the religion profile box empty but still enacting their religion, it confirms that many do not see the space as a worthy vehicle for defining their beliefs. To study this in more depth I propose a more qualitative research method, using each large Facebook religious page for each major religion to pose the question of whether the participants of that group do or do not display their religious preference on their Facebook profile page and why they make this decision. In returning the data with their religion (if any) and their area of residence, then one could start to investigate trends in how public their religious beliefs are online and be able to map trends within borders and religion.

This should be a vital research pool in answering questions of if people view religion as being a shared, public experience in the online social sphere or if it more closely reflects the ‘private’, segregated nature of how religion is enacted in Europe today. Similarly will nations that have a more public religious life, such as the USA and, for instance, Malaysia, share the same publicness on their profiles? Finally, by mapping the uptake of religious specialist social networking sites and investigating the ‘publicness’ of their sites, one can draw conclusions over the general wish to keep religion out of the socially diverse zone of Facebook and how it may exist more pervasively as social communication is being articulated in the ‘private’ specialist social networks.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Armfield, G. & Holbert, R. L. (2003). The Relationship between Religiosity and Internet Use. Journal of Media and Religion, 2(3), 129-144.

Berger, Peter (1973) ‘The Homeless Mind’ Vintage Books: New York

Enzensberger, Hans Magnus, ‘Constituents of a Theory of the Media’, in The New Media Theory Reader, ed. Noah Wardrip-Fruin and Nick Monfort (MIT Press:USA 2003), pp. 259- 276.

Hill-Smith, Connie (2011) ‘Cyberpilgrimage: The (Virtual) Reality of Online Pilgrimage Experience’ in Religion Compass, Volume 5, Issue 6 (Blackwell Publishing:UK , June 2011) pp. 271–275

Tartoussieh, Karim (2011): Virtual citizenship: Islam, culture, and politics in the digital age, International Journal of Cultural Policy, 17:2, 198-208

Taylor, Charles (2007) A Secular Age, Harvard University Press, USA