Mobile Tweeting – recognising usage frequency, tendencies and social interaction differences

The Question

Academic research on Twitter has been rife since it hit off in 2006, with significant focus on two topics in particular- that of privacy and identity. Much that has been written by scholars of Twitter has generally been cautious, negative (labeling privacy as a problem) or positive in the sense of data accumulation (i.e what can be inferred or derived from data sets, indirectly or directly, for example Twitter lists). My biggest concern with the majority of the works is a lack of consideration or attention to the difference between mobile platforms. Tweeting nowadays can be done through a variety of mediums available to the user regardless of geographical location, whether that’s on a home computer, tablet, or mobile phone – there’s a good chance you’ll be able to tweet. Initially vibrant in Western societies this phenomenon is growing globally thanks to the increasing affordability and geographical range of 3G mobile devices, as well as accessibility to wifi in public spaces. Within the majority of works on Twitter that I’ve read, there seems to be a general assumption that when you’ve tweeted, that’s it. The analysis then begins once the tweet has been made – regardless of the device you used or geographical location, social situation etc, the tweet is a content statistic or a retweet or a mention – no before, just after. But what if the devices themselves had an influence on the user’s tweets? What if one of the device’s application interfaces was more appealing than another? Therefore inducing a more positive response from the user, consequently leading to more tweets? These questions may be impossible to answer, purely because they are situational and the amount of variables leading to one’s decision would be countless. But it is my belief that device aesthetics, particularly those of smartphone mobile devices, app interfaces (and the choice of apps) together with social situations in particular, may in fact induce a different type of tweeting, the former focused on tweeting frequency, the latter focused more on social interaction and behaviour.

Mobile Smartphone Apps Usage

Lenhart and Fox proved in their study that as of September 2009, ‘54% of internet users have a wireless connection to the internet via a laptop, cell phone, game console, or other mobile device. Of those, 25% use Twitter or another service, up from 14% of wireless users in December 2008. By comparison, 8% of internet users who rely exclusively on tethered access use Twitter or another service, up from 6% in December 2008.’ These numbers will have undoubtedly increased since that time, but importantly, what their study did demonstrate was that users were more inclined to update their statuses on mobile devices.

Which one do you use?

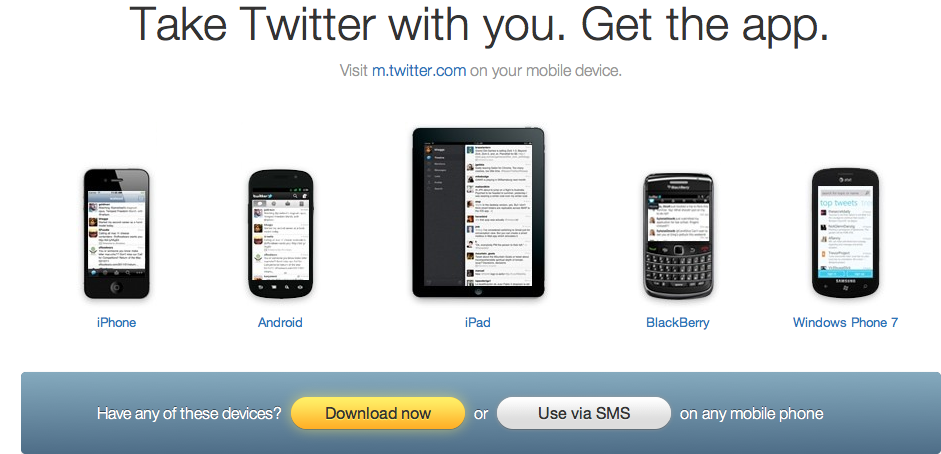

So people are tweeting from their mobile devices (smartphones in particular), considerably as well- that much we can confirm. Hypothetically, if there was data already readily available in which we could see, clearly for example: whether ‘x’ amount of users on Android phones tweet more than ‘x’ amount of users tweet on iPhones or Blackberrys – what could we derive from this information? Do we simply put this down to certain situational variables, accessibility to internet etc? There is no doubt a large number of explanations for such a statistic if it were true.

Some of the questions you’d need to ask are: does the Twitter mobile app for Android invoke a different response to that of the Apple app or Blackberry app? Different app interfaces for different platforms may elicit different responses. Blackberry tweeters for instance may be more inclined to tweet more regularly than Apple iOS users. The Android marketplace offers more than one kind of Twitter App. Is it likely therefore that Android users using a third party app are more inclined to tweet than an Android user using the official app – purely down to interfacial differences and aesthetics or enhanced features? Kate Crawford for example, argues Twitter’s appeal is in the intimacy that it provides. Can this intimacy be derived through aesthetics as well as peer to peer interaction?

We could go further and ask whether users more inclined to tweet if they use the Twitter ‘widget’ on their mobile phone. If the widget were in fact not available – would they tweet less frequently? Or what about other apps like Nike (where it will automatically let people know of a running route you’ve done) or FourSquare(where you ‘check-in’ to certain locations)? Is there no significance in tweeters using these apps? Maybe people are trying to elicit social interaction with others by doing so, as they may do within other social networks.

Do we simply put it down to individual preferences and motivations and leave it as that? What if we’re neglecting something key to twitter in general? There may be possible trends and tendencies, particularly in relation to social interaction or app features, that we’re just not aware of because of no available data. It may be an avenue worth exploring, even if it is purely due to the sheer number of mobile users tweeting.

Real life Social Interaction

The second question is more behavioral in nature and does touch upon one of the most debated subjects within Twitter academia, identity, but is still in relation to mobile tweeting. Specifically, does mobile tweeting when one interacts with a group socially in real life elicit a different type of tweeting behaviour?

Of course, there have been studies done on situational scenarios: (watching TV – Wohn) and geographical locations (Danah Boyd, Sarita Yardi). For example, geographically, it may be safe to assume that if a user is at his or her home, they may be less inclined to tweet that fact than if they were out at a restaurant. Boyd discovers a correlation between local physical proximity and local events – in which case tweeters would be more inclined to tweet specifically on that event.

These questions I’ve put forward in my blog are in fact a response to Marwick and Boyd’s articles and Wohn’s. In particular, Danah Boyd explores the social interaction of tweeters, how they present themselves differently to when they may meet face to face (as how anyone presents themselves differently depending on the social context). The question of social interaction is a response to her findings and touches upon authenticity and our audiences.

Twitter does not require a reciprocal relationship – but real life social interactions do. If the user is – for example with friends – and they did tweet, would they tweet differently? Would they be more personal in their tweets? Would there be a trend quantitatively? We know that social interactions between people differ depending on whether it is online or offline. For those that are concerned with their online self presentation and identity build up, how differently do they tweet when in real life social environments?

Boyd would suggest we do tweet differently as it depends on the identity you’re protecting or keen on exhibiting:

‘On the one hand, Twitter is seen as an authentic space for personal interaction. On the other, social norms against ‘oversharing’ and privacy concerns mean that information deemed to personal may be removed from potential interactions… the desire to have ‘fans’ or a ‘personal brand’ conflicts with the desire for pure self expression and intimate connections with others.’

The question may be then – do these conflicts dissipate if tweeting occurs in real life social interactions?

Methodological considerations/ problems/ scope

The second question is a loose cannon. Academically trying to answer such a question is interdisciplinary and significantly out of scope – not even considering the considerable quail-quantitative necessities either.

Very briefly, how can you measure if one tweets ‘differently’? I would use Boyd’s thoughts on how Twitter users form their tweets around ‘imagined’ audiences. When these audiences then become real, their tweeting behaviour that they’d normally adhere to online may change (diction, syntax, pure self expression, intimacy).

Wohn categorised the types of tweeted content into a matrix –‘attention, emotion, information, and opinion.’ While he does not specifically mention the fact it was tweeted through a mobile platform, he mentions, quite importantly, that the differences in messages tweeted correlates with TV watching and the programs they watch. The difference is in the activity.

If there is one plausible direction a research of this kind could take it would be in a thorough analysis of the different twitter apps currently available across mainstream smartphone platforms (Apple’s iOS, Google’s Android and Blackberry’s OS). A thorough exploration of these apps accompanied by a qualitative survey of its users should be efficient to determine if they invoke certain responses and a lower/higher frequency in Twitter usage.

If crawlers can determine whether a tweet came from a specific mobile device or not, a quantitative study would be feasible.

In terms of demographics it may be wise to categorize users into infrequent and frequent tweeters. For instance we could judge a user on his/her influence (using Cha’s measure of influence, indegree (followers of a user), retweets and mentions). For instance, a user with a higher influence rating (accumulated over a short period of time) may be more inclined on tweeting their exact happenings when possible using a mobile platform. There may be a correlation between user’s with higher influence ratings and mobile device usage.

Currently the methodology is loosely formatted and the above questions are not coherent in structure. Consequently, considering the resources available, the study may hinge on whether the specific crawler can be coded (I believe it can).

Final Thoughts

Mobile use is changing and evolving. A 2010 survey by Zokem of mobile phone users in the USA and Europe found that 29% of our time is spent on phone messaging, and only 23% on voice calls.

This has clear implications for online social networking. Some of these implications I’ve covered in this blog include identity management and frequency of mobile social networking usage dependent on feature availability.

Other questions that sprang to mind where on group polarisation and homophily – surely they link in with the above thoughts?

As features evolve on mobile devices, and in turn the apps as well, do our ways of using them change too? Resulting in more frequent or ‘different’ tweets (photo tweets for example in the future)? Can we derive specific trends through mobile twitter usage? Are users more inclined on simply reading other tweets rather than formulating their own if they used a specific Twitter app and were unaware of a third party improvement? In my opinion a thorough examination of the correlation between Twitter usage frequency and app interface aesthetics is worthy of attention.

Cited Works:

T.Ahonen, Moore, Alan.. (2011) Communities Dominate Brands

Wohn, D. Y., and Na, E.-K.. (2011). Tweeting about TV: Sharing television viewing experiences via social media message streams. First Monday, 16 (3).

Lenhart, Amanda, and Fox, Susannah. (2009). Twitter and status updating.

Sarita Yardi, Danah Boyd.. (2010), Tweeting from the Town Square: Measuring Geographic Local Networks..

Cha, Meeyoung, Haddadi, Hamed, Benevenuto, Fabricio, and Gummadi, Krishna P.. (2010). Measuring User Influence in Twitter: The Million Follower Fallacy. Proceedings of ICWSM. AAAI.

Crawford, Kate. (2009). These Foolish Things: On Intimacy and Insignificance in Mobile Media.In Goggin, Gerard and Hjorth, Larissa (Eds.), Mobile Technologies: From Telecommunications to Media.