Interview with James Robinson: Mapping the World’s Signal

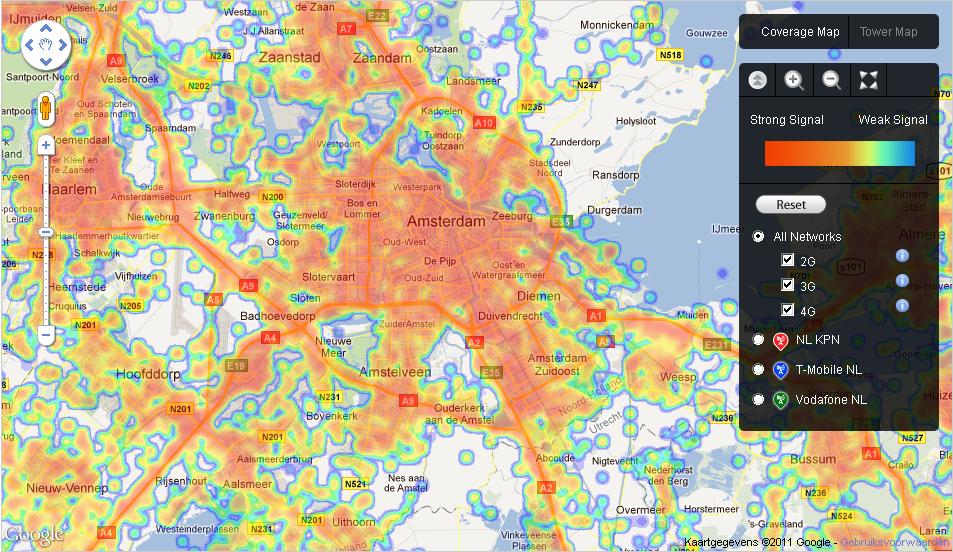

A couple of weeks ago I wrote a blogpost about Open Signal Maps, an application for android that maps the world’s signal. I used the application myself for several days and it worked pretty fine and gave me better understanding of signal strength in my area. But I was still curious about the story behind this application. I contacted the makers of the application and got a email back from James Robinson, co-founder of the company. I wanted to know more about this application because it has several quite interesting elements in it, among them are; crowd sourcing, data mining, data visualizations, mapping and it’s an android only application.

Started as a company in selling Cellular Repeaters (to boost cell signal), the co-founders got the idea of mapping the world’s signal through the use of a mobile application. The company is based in London and San Francisco but it operates all around the world. With help of online collaborating tools they keep in touch with each other. With an average of 10 thousand users on a daily basis and more than a million downloads overall, we could say that this application is a success.

The core principle of the application is using to the crowd to map the world’s signal. But why would like to map the world’s signal, isn’t that the job of the carries like Vodafone and AT&T? Robinson explains that it is important to have an impartial view on signal strength. Besides he argues; mapping resources is the best way of understanding inequalities in its distribution. By doing this you could actually research opportunities for improvement.

Further on, Robinson argues that Android is a pleasure to code for and it also allows you access to more things than iPhone. At the moment they are making an iPhone application as well but it has less features than its Android counterpart. One the key elements of the company is crowd sourcing, they crowd source their data, bugs and lots more. But what is interesting about crowd sourcing, according to Robinson, is that the users are more passionate about the application. Users have a stronger link with the application because they feel more empowered. They are still searching for Dutch people that want to help to translate the application into dutch version.

Further on, Robinson argues that Android is a pleasure to code for and it also allows you access to more things than iPhone. At the moment they are making an iPhone application as well but it has less features than its Android counterpart. One the key elements of the company is crowd sourcing, they crowd source their data, bugs and lots more. But what is interesting about crowd sourcing, according to Robinson, is that the users are more passionate about the application. Users have a stronger link with the application because they feel more empowered. They are still searching for Dutch people that want to help to translate the application into dutch version.

I would like to thank James Robinson for the interview and his quick reaction on my email. Furthermore, I am defiantly looking forward to some new features in the future. Especially the one where you could see how much time you spend on 3G versus other technologies, what your signal quality is and what these values would be if you used a different network. I think that this feature will has a huge impact because it could shows us exactly where communication companies have to improve their networks.

You can read the whole interview with James Robinson below.

Could you introduce yourself and your company, how it all began. (Who developed the app? Who is/are the owner(s)?)

There are 4 of us cofounders, we all studied Physics together at Oxford University (apart from me, I studied Physics and Philosophy), so we’re friends as well as colleagues. The three others, Sam, Brendan and Sina, founded a company selling Cellular Repeaters (Repeaterstore.com) these boost cell signal and are really popular in the US. So they became interested in these problems, I joined a couple of years ago and began building Android apps, after trying various things we had the idea of mapping the world’s signal.

Where are you based?

We’re currently in San Francisco talking to network operators and meeting lots of people involved with crowd-sourcing and location. Although we’re all English we tend to work from different countries a lot of the time – collaborating online. I spend a lot of time in Buenos Aires. We meet up in London quite a bit where we work out of a place called Techhub.

Could you shortly introduce the application on what it does and how it works?

The application is a signal dashboard for your phone. It shows where your signal is coming from and the towers your connected to, it presents all the strength metrics we can get from Android, there’s a graph to and a speed test. We think it’s the best signal tool there is. The app also runs in the background, if you let it, and will log data to an internal database (so there’s no interruption if signal is unavailable) this data is sent to our servers periodically via wifi. We then map that data.

What was the reason for you to develop this app?

It’s important to have an impartial view on signal strength. Partly it’s about enabling consumers to choose the best carrier. I also believe, signal – like other resources – should be mapped, it’s the most effective form of understanding inequalities in its distribution and opportunities for improvement. For instance, if you’re a government interested in providing the best infrastructure for your people, it’s vital you understand things like latency and data transfer speeds, improving these can make big differences of very common mobile tasks – like checking email.

Why did you choose for Android, instead of other operating systems like iOS, Blackberry Os or Windows Phone?

Android is a pleasure to code for and it also allows you access to more things than iPhone. We can’t even access the signal strength on on-jailbroken iPhones. That said, we are building an iPhone app that will allow users to run speed-tests and manually report problems (slow internet, dropped call and so on).

It is almost a year ago that you launched the app, what were the ups and downs?

Every time a new version of Android comes out something will break, dealing with the proliferation of different Android devices is also a pain. On the plus side, a whole lot of people have downloaded the app and the project has been featured on Techcrunch and we think it’s going to be an amazing resource – we still consider ourselves in beta.

Can you tell me something about the people that are using the app? (How many people have downloaded the app? How many people use the app on a daily basis? What are their nationalities?)

Google have just introduced real time analytics and it’s really fun to see hundreds of people using your app at any instant in time. We have 1m downloads. In a good day, 10k different people will open it up, but it does run in the background (if permitted) so we collect data continuously from a lot more. After the US, the app is most popular in Russia and after that in Italy, which is quite interesting and indicative of the signal problems in these countries.

The app is free to download, would it have the same success if it was a paid app?

Definitely not, especially on Android. It’s hard to say how many downloads it would have, we’d recommend the fremium or add-supported model to most app developers who are after revenue.

What is your business model with this application?

We’re still considering this! We’re bootstrapped off other business we’re running.

We’re considering:

– Developing the website to provide impartial recommendations for handsets and networks and making affiliate sales through this.

– Consulting for the networks. There are a lot of things we think we could help them with – spotting holes in their coverage, providing them with information about their competitors – who might be good to partner with to share coverage or for roaming contracts.

– We’re not fans of banner adverts in apps, but if we can advertise in an unobtrusive way that can help users then we’ll consider that. Current ideas include sponsored wifi access pints – cafés that offer free wifi could appear as icons of a different colour.

Your app is based on the principle of crowd sourcing data. Why did you choose for this model? Did you already had some experience in crowd sourcing?

No, but lots of familiarity. We’re big fans of all crowd-sourcing projects, especially ones that mix in mobile and mapping (like Ushahidi), it’s such a powerful combination.

What are the positive/negative aspects of crowd sourcing in your experience?

Both the best and worst thing is that people get more passionate about a crowd sourcing app.

This is a good thing because people download the app more, they use it more and, most importantly, they send us lots of feedback, bugs they’ve spotted and features they’d like to see. It can sometimes feel bad (though maybe it isn’t really) because we feel a pretty high responsibility to our users. For instance, we’ve spent several months not doing much work on improving the speed at which the heatmaps are refreshed with new data that is collected (we haven’t updated the maps in months), we’ve been working on other stuff we gave a higher priority, but we know it’s annoying for users when the areas they have mapped don’t show up immediately. The good news is we are now turning our attention to this now.

I read on your blog that the app is not working well on the Galaxy S2, you immediately started to ask your users for help. Is this typical how you work, always ask the users/crowd for help?

Good question! Since we asked for help increasing the priority of this bug the number of people who’ve raised that technical issue with Android has gone up from 10 to over 100. Unfortunately it’s still not fixed, but it’s got to help.

We try to use crowd-sourcing wherever we can, for example: we put out a blog post asking people to help translate the app, from that we got translations in French, German, Italian and Russian (thinks Pierre, Ricardo, Evgeny, Alessio!) If there are any Dutch speakers who want to help, get in touch!

Is this the way to show the world the real statistics of cell phone signal compare to what communication firms, like AT&T or Vodafone, show us?

There are a number of differences between what we’re doing and what the big firms do which we think make us more reliable.

Firstly: we collect data in a different way. The large firms do “drive-testing” which is where vans drive around with phones inside. A big company may have 100 vans on the roads, driving all year round. This is really inefficient in terms of the fuel used, it’s also not necessarily representative of where phones are used. Typically the drive-test routes cover most of the motorways and many secondary roads, but only a small proportion of the suburbs. Our app is used all over, and it’s used more where people care about signal or have problems finding it, it collects data throughout the day (drive-testing takes place during particular hours) so we get a broader picture that really measures a users’ experience of their signal.

Secondly: we present data in a different way. Each network will have their own methodology for preparing the data and then turning it into maps – they’ll use different colours, different scales – it’s impossible to compare their maps fairly. We’re still working on how to make our heatmap overlays as clear as possible, but we’ll always treat all the network operators in the same way.

You almost mapped the whole world, are there still places you want to map or is this app coming to an end?

We’ve got great spread of data – Android is such a global platform, we’ve got data from over 200 countries, but we don’t see the app as an ongoing project for three reasons. Firstly, we want to get a more and more detailed picture, to see which street corners have bad signal, not just which countries. Secondly, new networks and network technologies (e.g. 4G) are being developed all the time, monitoring the rollout of these is crucial – perhaps even more important that looking at 3G (which has pretty good coverage in Western Europe now, though issues remain in the states and elsewhere). Thirdly, we want to be a fresh resource, that can spot strain on networks – show who’s improving and who’s not investing in their infrastructure.

Are you developing extra feature for this app?

Very much so. Aside from working on apps for other platforms we have a lot of plans for the Android app. Here are a few of them:

– Statistics on your signal – how much time you spend on 3G versus other technologies, what your signal quality is and (and this one will be tricky) what these values would be if you used a different network. We want to integrate these with the website so you can share these online.

– Competitive cell and wifi collection – who’s mapped the most points today?

– Better presentation of the wifi data – maps of open nearby hotspots with the ability to edit them – say whether they are genuinely open and add details like what sort of place it is (café, library and so on)

What else would you like to map in the future?

There’s so much stuff that could benefit from crowd-sourced maps:

– Pressure readings. The Xoom and recently announced Nexus Galaxy both contain barometers. You could have data collect in the background and sent in realtime to a map, and create very precise maps of weather patterns.

– Cemeteries. I think it would be fascinating to have a survey of cemeteries and really useful for family history. People could use GPS to map grave locations and a mixture of OCR, manual input and photographs to record the graves. The data would paint a fascinating picture, from very personal stories, to information about the average life-expectancy by country and era.