‘Share and Share Alike’ The Democratic Future of the Music Industry

As early as 1997, WELL member Michael H. Goldhaber predicted the paradigmatic shift that would be brought about in the global economy as widespread use of the internet began to take place. He realized that in these coming times of unavoidable information overload, getting attention (and most importantly maintaining it) would be the deciding factor. No sector of the economy demonstrates these savant-like predictions better than the current state of the music industry, as Goldhaber further demonstrates – “The attention economy brings with it its own kind of wealth, its own class divisions – stars vs. fans – and its own forms of property, all of which make it incompatible with the industrial-money-market based economy it bids fair to replace. Success will come to those who best accommodate to this new reality.”

This sentiment – that there is no point in fighting the change, rather the key is to accept it, process it and then adapt in the most suitable manner in order to survive – has since been echoed by a number of others. Radiohead frontman Thom Yorke “It will be only a matter of time—months rather than years—before the music business establishment completely folds. [It will be] no great loss to the world” said Radiohead lead singer Thom Yorke.

manner in order to survive – has since been echoed by a number of others. Radiohead frontman Thom Yorke “It will be only a matter of time—months rather than years—before the music business establishment completely folds. [It will be] no great loss to the world” said Radiohead lead singer Thom Yorke.

This statement can be heard being made the world over as record sales continue to plummet into essentially insignificant amounts. More and more people from all ages and all backgrounds become more accustomed with the sophisticated use of technology many are beginning to question why anyone would voluntarily spend time and money on a hard copy edition of their favourite album when only a few clicks in the right direction can lift hundreds of albums from a torrent site into your music library, with little time invested, and for most people no risk involved at all.

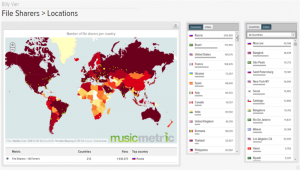

Yet up until now this new method of music consumption has been shrouded in secrecy, due to the illegal aspects involved. However recent figures published by the UK analytic company Musicmetric has changed that completely. Released earlier this month, the study compiles information from a number of sources, most prominently the BitTorrent file sharing website, and then uses this information to create charts and graphs, facts and figures, in much the same way that the traditional charts have always done.

On the business side of things Musicmetric offer services to potential customers, most likely artists interested in furthering their careers, on who is listening to their stuff, how they are listening to it and perhaps most importantly where. This is the key fact here – as music sales spiral downwards touring becomes the main, and at times only source of income for the majority of artists, from all manner of genres. Thus the tools offered by companies such as Musicmetric, (that have in fact existed in one form or another since the days of MySpace) are vital to artists, for example in indicating where the next leg of their tour should take place and are themselves demonstrative of how the industry’ is so drastically changing and adapting to the digital age.

A case in point of an artist who has succesfully adapted – does the name Billy Van ring any bells? Most probably not. Yet in the past year Billy (a music graduate from the US) was the most downloaded musician in Brazil, India and Greece, with a combined tally of over 50 million hits. Yet Billy has never sold a record – he is the perfect contemporary example of the attention economy that Goldhaber once referred to. His music was offered as a bundle package, included with any BitTorrent download or update – thus gaining him incredible amounts of targeted attention. This tactic, combined with a prolonged social media campaign, propelled Billy to the top of the illegal download charts the world over, transporting him from relative obscurity to global fame in only a matter of weeks.

A case in point of an artist who has succesfully adapted – does the name Billy Van ring any bells? Most probably not. Yet in the past year Billy (a music graduate from the US) was the most downloaded musician in Brazil, India and Greece, with a combined tally of over 50 million hits. Yet Billy has never sold a record – he is the perfect contemporary example of the attention economy that Goldhaber once referred to. His music was offered as a bundle package, included with any BitTorrent download or update – thus gaining him incredible amounts of targeted attention. This tactic, combined with a prolonged social media campaign, propelled Billy to the top of the illegal download charts the world over, transporting him from relative obscurity to global fame in only a matter of weeks.

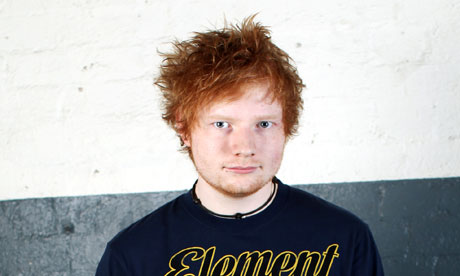

Another example of an artist who has managed to adapt and thus maintained a high level of success in the face of internet piracy, can be found in the form of the English singer-songwriter Ed Sheeran. He realised  that whilst no hard income was arriving from the majority of his downloads (he sold 1.2 million but was downloaded illegally over 8 million times) this was not necessarily a bad thing – “So nine million people have my record in England, which is quite a nice feeling.” A ‘nice feeling’ may just be Ed’s way of describing the revenue generated from an international tour that sold out across a number of venues – “There’s a decent balance between them – you can live off your sales and you can allow people to illegally download it and come to your gigs. My gig tickets are £18 and my album is £8, so it’s all relative.”

that whilst no hard income was arriving from the majority of his downloads (he sold 1.2 million but was downloaded illegally over 8 million times) this was not necessarily a bad thing – “So nine million people have my record in England, which is quite a nice feeling.” A ‘nice feeling’ may just be Ed’s way of describing the revenue generated from an international tour that sold out across a number of venues – “There’s a decent balance between them – you can live off your sales and you can allow people to illegally download it and come to your gigs. My gig tickets are £18 and my album is £8, so it’s all relative.”

Yet it isn’t only up and coming artists that realize that piracy doesn’t necessarily have to represent a threat. Even the legendary Neil Young, who’s been in and around the music industry for nearly half a century says piracy doesn’t even affect him at all. He sees the internet as simply a new medium to replace the old – the ‘new radio’ – and instead of dismissing it as detrimental to the industry we should instead recognise its immense potential. In Young’s eyes piracy is simply the new tool through which music travels the world, and this should be celebrated – not criticized.

However, there are many within the industry (admittedly most commonly on the business side of things) who disagree with the rosy pictures being painted by Young and Sheeran and the rest and there are some who have grave fears about what this rise in illegal music consumption could do. The RIAA, in contrast to the artists mentioned above, have provided another, much harsher, statement on digital music piracy, as a bid to combat its growing dominance over the market. They argue that illegal downloading a song may not feel as a crime, but the accumulative impact of billions of songs downloaded illegally is undeniably devastating. Whilst it would be easy to dismiss their claims as simply those of a generation left behind, and fearing for their own economic survival, one of the reasons they come up with to exemplify this devastation and one which does hold truth, is the lack of compensation to all the many individuals who helped to create the particular song in question – the sound engineers, the studio staff – ‘the little guys’. Thus the RIAA come to the conclusion that “piracy undermines the future of music”. One look at the examples given above however, and one can see that this statement is essentially flawed. Loz Kaye, the leader of the UK branch of the ever-growing Pirate Party recently commented that the industry heads are slowly realising that their expiry date may be just around the corner – “The truth is, why [music industry figures] are complaining so much is that with a properly functioning internet, and a properly functioning economy, the big players are no longer necessary.”

And it is sophisticated services such as Musicmetric and Beluga (Grooveshark) that are further identifying just how easily replacable many industry figures actually are. Whilst the earlier days of music piracy were dominated by poorly constructed services such as Limewire and Napster, thus the industry managed to fight back and eventually claim a small victory over piracy, their modern and updated counterparts are tools that can provide figures comprehensive enough to be analysed as if they were official charts themselves, and thus real growth can take place.

These analytic services are themselves part of a wider movement that is aiming to and currently succeeding in creating a ‘music industry’ of their own (through official channels such as Spotify and Last.fm and equally more underground communities such as the popular file sharing site The Pirate Bay) – one where label bosses are not allowed to dominate and dictate and where marketing takes a guerilla form (often through social networking means etc.) – thus allowing for a more natural progression in terms of both global and local music taste-making. Whilst the future of the industry has always been notoriously difficult to predict, at least this can be said – tools such as Musicmetric demonstrate that change is possible; that it is inevitable, and thus only two choices remain – cling on to the old model of hard copy sales and promotional tours or adapt and join the new movement of online music sharing communities that are free from the old constraints of ‘big label’ dominance. The label bosses have to realize that the world in which we now live is dominated by the new ‘attention economy’, where, as Goldhaber predicted in 1997, those who wanted to succeed, are those who are quickest at adapting and accommodating to the new reality.

Kieran Lewis & Basri Hoogstrate