A Bloody Trail Behind Our Mobile Life: a fair trade mobile phone

“It is time to be asking questions about technology. Where does it come from? Who makes it? And for what?” ― Bandi Mbubi (@ TED talk)

Explosions of two plants that make Apple gadgets. A series of employee suicides at the Foxconn factory in China. Continuous reports of harsh working conditions. The situation is not much different in the field where the raw materials for mobile phones are extracted: the famous ongoing battle over “conflict minerals” in Congo.[1] Have you ever imagined this kind of story behind a smartphone in your hand?

The global production/supply chain of the mobile phone industry has always faced labor challenges as it consumes raw materials mined under harsh conditions. Many manufacturing workers are subject to low wages, long hours, tough and unhealthy working conditions.

This issue was put in the context of corporate social responsibility (CSR) so that the multinational companies have been under an increasing public pressure in monitoring their production/supply chains since 1990s. “In response to concerns regarding labor and social issues in the IT electronics manufacturing industry, many multinational companies adopted programs of corporate responsibility and some now also participate in voluntary industry initiatives.” [2] The prominent one is Electronic Industry Citizenship Coalition (EICC) with its Code of Conduct. It was established in 2004 by leading IT manufacturers and their suppliers “in order to improve the often precarious working conditions prevailing in the manufacture of electronic products. The EICC Code of Conduct’s demands for employees include freedom of association, appropriate safety standards in the workplace and the avoidance of child labor.”[3] However, this code was criticized by NGOs for its incongruence with the currently valid ILO standards.[4] Despite such company-level efforts, the countries where the extraction of raw materials and the production of commodities in a large quantity happen still have low labor standards.

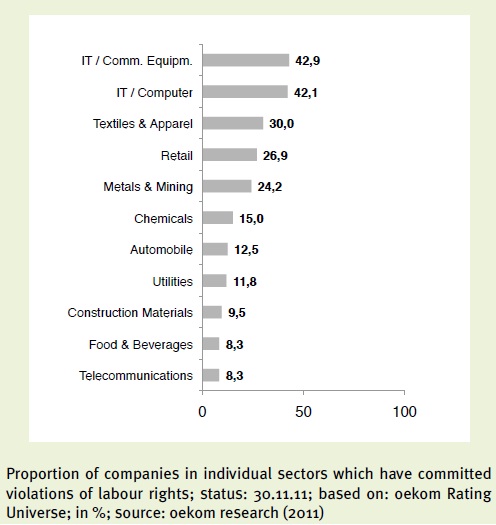

According to the oekom research paper, “the manufacturers of mobile phones and computers rank among the worst of the sectors which violate internationally recognized labor rights” (Figure 1). The mining industry also shows labor rights violations frequently.

Why is it so hard to terminate this vicious cycle of the mobile phone industry? According to the ILO’s IT expert Paul Bailey, “because of cost advantages, commodity suppliers are often found in export processing zones in low-wage developing countries. The lower end of the value chain is therefore of particular importance when we consider the labor and social challenges arising from participation in global production systems, and especially from the operations of multinational enterprises.”[5]

Why is it so hard to terminate this vicious cycle of the mobile phone industry? According to the ILO’s IT expert Paul Bailey, “because of cost advantages, commodity suppliers are often found in export processing zones in low-wage developing countries. The lower end of the value chain is therefore of particular importance when we consider the labor and social challenges arising from participation in global production systems, and especially from the operations of multinational enterprises.”[5]

Although many multinational companies (for example Apple, Nokia, etc.) adopted programs of corporate responsibility and participated in voluntary industry initiatives in response to concerns regarding labor and social issues in the IT electronics manufacturing industry, [6] “it’s not clear how these are monitored, enforced, or how much in common they share across the electronics industry.”[7] Such commitments at the level of multinational companies are weak in terms of legally binding force so that the mobile phone industry keeps pursuing their own profits usually by reducing the labor cost-the largest manufacturing cost. Thus “employees are continuously enforced to work faster, while maintaining high quality work, and at the lowest wages acceptable.” [8] Therefore, as Professor Yu Zhou pointed out appropriately, [9] we cannot move beyond the limits in the existing corporate social responsibility system if the entire process of current mobile phone industry is monitored mainly by profit-maximizing corporations.

Corporate social responsibility standards are easily flawed in this way by the global companies’ eagerness to maximize their profits, what can be an alternative then? How about the concept of fair trade? According to Scott Nova, executive director of the Worker Rights Consortium (WRC), a fair trade model has been successfully implemented for goods such as coffee, fruits and apparel, as a means to ensure fair compensation for small agricultural producers. However, it will be more complicated and problematic applying it to the IT sector where there is an employer-employee relationship.

He said “in order for the model to work in that context, you need buyers that are willing to take genuine responsibility for their suppliers’ labor practices and are willing to pay prices, and accept delivery schedules, that are consistent with good labor practices. It is generally not enough for the brand to just pay a small fair trade premium—greater expense and responsibility are required.”[10]

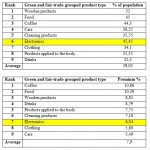

It is true that consumer purchasing habits in terms of IT products are largely price-driven.[11] As shown in the tables above[12], compared to other types of products, people are very willing to pay more for fair trade electronics but the amount of premium they want to pay is relatively lower. It means that people are more sensitive to the price as to purchasing the electronic products and this worsens the situation where the companies tend to avoid abiding by any fair trade initiatives for their profits. More simply, we witness our insatiable demand for new IT products in reality, the long lines outside Apple stores!

Then, is it impossible to have a fair trade mobile phone? It seemed so even until 2010 when Bob Nefkens, one of graduates of our master program, said “For us consumers it’s impossible to choose a ‘blood free’ mobile” in his post.

But FairPhone is now actually on the way to becoming reality. FairPhone is an initiative of Waag Society. It began by “investigating the production of raw materials for mobile electronics” including mobile phones. Most of these raw materials come from Congo where a majority people work at the mines under harsh working conditions and even a lot of children and young people are involved in the industry.[13] FairPhone aims to find another way to “produce the necessary raw materials in order to change the supply chain and the way the industry works. Therefore, FairPhone works on the graphic and technical design of fair telephones; designing a new way of doing business.

“The most common argument used by the consumer electronics industry as to why there are no certified fair electronic products is that the production chain is too complicated and insufficiently transparent. The industry claims that it cannot even monitor activities three steps back in its own chain, and has absolutely no insight into the route from mines in Africa to the processing facilities and production plants in Asia. Above all this, it is often mistakingly stated that consumers do not care for responsible products. The team of FairPhone knows that it is possible to gain that insight. And getting consumers excited about it is key in the process.”—FairPhone

From this statement, we can observe that FairPhone clearly understood the limits of the current corporate social responsibility system and took the very appropriate step to generate the market demand for fair phones.[14] Such an attempt of FairPhone was continued at the last Discovery Festival (Figure on the left). FairPhone project had people disassembling mobile phones so that they could think about all the materials of mobile phone and the inequitable process behind the mobile phone.

In order to intervene in the global production/supply chain of the mobile phone industry and the global companies’ monitoring system, it is important to foster the local community’s own capacity. FairPhone also seems to take the right direction in this aspect as it actively studies and interacts with the local community and tries to involve them in their project as shown in the following video.

Although only time can tell whether FairPhone would be successful or not, FairPhone seems to step off on the right foot so far, which makes us look to its future. Now, in addition to going for iPhone 5, you have another option to submit your email address to the waiting list for FairPhone.

[1] Congo is a hot spot raising the issue of ethically sourced materials. “Non-governmental organization (NGO) Enough Project explained that armed groups in eastern Congo earned hundreds of millions of dollars every year through trading what has been dubbed ‘conflict minerals.’ According to Enough Project, “These minerals are in all our electronics devices. Government troops and militias fight to control the mines, murdering and raping civilians to fracture the structure of society.” [source]

[2] ILO, “Corporate social responsibility in the IT sector: Is it responsible enough?” (13 April 2007).

[3] oekom Research, “oekom Position Paper: Working Conditions in the Supply Chain” (December 2011).

[4] It means, for example, “where a manufacturing country bans the formation of trade unions, the employees affected have no recourse to the EICC Code.” (oekom Research, 2011)

[7] Tom Foremski, “Foxconn suicides: Time for fair trade electronics? Would you buy a fair trade iPhone?” (ZDnet, 27 May 2010).

[9] Yu Zhou, “Bring Fair Trade to Electronics” (29 January 2012)

[10] Ryan Huang, “‘Fair trade’ IT products to improve working conditions?” (ZDnet, 2 March 2012).

[12] Peter-Paul de Leeuw, “The Willingness to pay for Green and Fair-trade Product Types”, Master Thesis Erasmus University Rotterdam, 2011.

[13] Refer to Nefkens’ post for the details about situations in Congo

[14] There have been long efforts for raising public awareness and creating the market demands for fair trade mobile phone. Make IT Fair is notable.