The Quantified Self & Big Data: causing a new turn in science?

How much time do you spend on Facebook? How many of your friends are living in Amsterdam? What is the best time to wake up in the morning? These questions are hard to answer and can take a lot of time if you try to find out manually. However, there are appearing more applications and tools that help you understand your own behavior in an easy way. This self-monitoring and personal data collecting is often referred to as the quantified self. Never heard of it? Do not worry, co-founder of the quantifiedself.com Kevin Kelly himself has a hard time defining the new concept: ‘I still do not know what the quantified self is, but we are using this whole thing [organizing meet ups and the website] to define it’. [1]

Kevin Kelly – Quantified Self Co-Founder from Gary Wolf on Vimeo.

The Quantified Self

Kelvin Kelly, founder of Wired, founded the platform qantifiedself.com with journalist Gary Wolf, and introduced the concept to a broader audience. They wanted to collect all the tools that people use to collect self-knowledge through numbers and research the relevance of self-knowledge. In his presentation about the quantified self on one of his events, Kelly is positive about the notion of self knowledge and the change it can bring to science and data processing in the broader sense. He argues that science can change by research tools, like the microscope brought new questions and answers. With the current introduction of new tools and ways of processing personal and social data, we have the ability to perform research about ourselves that has not been possible a couple of years ago. ‘It is actually changing the way we do science’ he says.[2] In contrast to most other research methods like surveys, the quantified self only looks at one example, one individual. Kelly believes that this self experimentation is at the frontier of changing the scientific method.

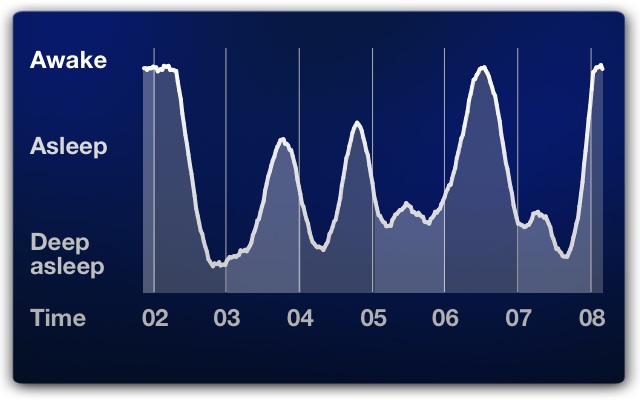

An example of a quantified self smartphone application is Sleep Cycle: ‘A bio-alarm clock that analyzes your sleep patterns and wakes you when you are in the lightest sleep phase’. [3] The application uses the accelerometer in iPhones to monitor movement to determine which sleep phase the user is in. The user can view personal graphs about his or her sleep and analyze data about him or herself. This data can then be used for personal ends, like waking up at the right moment or knowing the effects of alcohol on sleep.

Like Kelly, I believe that this new way of gathering data and doing research will change the way we perform science. It is citizen science: everyone can do it and it gives answers to mundane questions like: what am I doing when I am sleeping (Sleep Cycle), and what is my running progress (Nike + Running App)? Nobel Memorial Prize winner in Economics Daniel Kahneman did research about human judgment and found out that humans are actually not very good at self judgment. Introducing the concept of ‘peak-end rule’ he describes the phenomenon that humans tend to remember only the peak edges; the things in between peaks are easily forgotten. ‘We judge our experiences almost entirely on how they were at their peak and how they ended.’[4] Therefore, having specific data about your own behavior can fill the gaps in your own judgment.

The Nike+ FuelBand uses a sports-tested accelerometer to measure your movement in NikeFuel, a universal metric of activity. Source: nike.com

Questions and Problems

This all sounds very promising, but there are some questions about this notion. For example, can data be valuable if only one individual is studied and no comparison is made? Are users able to study themselves and can they make sense of the data in an objective way? And can general claims be made out of data about the quantified self?

One of the problems that I want to highlight is the massive amount of data that needs to be processed, since each user has its unique dataset. With all the new tools available, researchers are coping with enormous quantities of data produced by and about people, things and their interaction. And for this reason, new media critic danah boyd is describing the current time as ‘the Era of Big Data’. [5]

‘Big Data is notable not because of its size, but because of its rationality to other data. Due to efforts to mine and aggregate data, Big Data is fundamentally networked. Its value comes from the patterns that can be derived by making connections between pieces of data, about an individual, about individuals in relation to others, about groups of people, or simply about the structure of information itself’ [6]

Social networking site Facebook is facing this exact problem right now while working on a new tool: Graph Search.

Video can also be found here

Facebook as Data Set: Search Graph

Tools like Wolfram Alpha can be used to get insight in a specific Facebook network, but Graph Search by Facebook distinguishes itself by making personal data easy accessible and searchable. Until now it was only possible to use the Facebook search bar to look for friends and pages; the new tool will enable users to search phrases linked to specific interests and the likes of their friends.[7] For example, if you are looking for a good dentist in Amsterdam, you can search for: ‘Dentists in Amsterdam where my friends have been to’. A list of dentists liked by your friends appears, provided with some extra information by search engine Bing.

This tool is a new step towards using Big Data in an easy accessible way. Nevertheless, indexing all of the data is a big problem for Facebook and other software developers when creating new tools for understanding Big Data. Search Graph is still in early stages and Zuckerberg himself said it will take a long time before completion.

“Graph Search is a really big project, and it’s going to take years and years to index the whole map of the graph,” he said. [8]

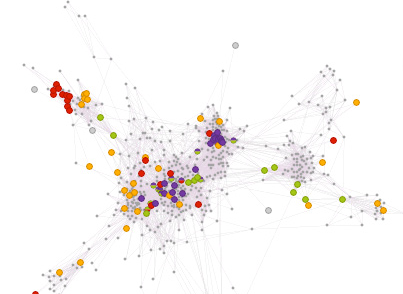

Wolfram Alpha provides personalized data and analysis of social data – like in this example the structure of your Facebook friends network. source: wolframalpha.com/facebook.

Personalized Search

Moreover, the introduction of Search Graph is a new development in the field of personalized search. The ability to get news from social media sites like Facebook is not a good development argued by author Eli Pariser.

‘As more and more people discover news and content through Facebook-like personalized feeds, the stuff that really matters falls out of the picture’[9]

He argues that features like personalization allow rapid access to more relevant information, but they present difficult ethical questions and fragment the public in problematic ways.[10] It is necessary that we start asking critical questons about what all this means, who gets acces, how it is processed.

Time will tell

In other words, there are a lot of developments going on in the field of data. Quantified self methods provide new insights and perhaps even a new turn in the field of science. However, there are some problems that come along with these new ways of collecting data. Data is not always objective, datasets are often too big, and can have a very social and personal stance. There are of course many more problems and questions to address when talking about the field of the quantified self, big data and personalized search. Nevertheless, it is clear that these topics have a lot in store for the future of research

———

.

[1] From Kevin Kelly’s talk at the first Quantified Self meet up, 8/29/12 – Storify in San Francisco.

.

[2]From Kevin Kelly’s talk at the first Quantified Self meet up, 8/29/12 – Storify in San Francisco.

.

[3] From http://www.sleepcycle.com/

.

[4] From Wikipedia, visited on 6 March 2013: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peak–end_rule

.

[5] Boyd, Danah, and Kate Crawford. “Six provocations for big data.” (2011) – page 1.

.

[6] Boyd, Danah, and Kate Crawford. “Six provocations for big data.” (2011) – page 3.

.

[7] Zach Miners, IDG News Service

‘Facebook Enhances Social Search With Graph Search‘, networkworld.com. January 15, 2013.

.

[8] Quote of Mark Zuckerberg in: Zach Miners, IDG News Service

‘Facebook Enhances Social Search With Graph Search‘, networkworld.com. January 15, 2013.

.

[9] Eli Pariser. ‘Filter bubbles, meet Upworthy’, thefilterbubble.com March 26th, 2012.

.

[10] Eli Pariser in Boyd, Danah, and Kate Crawford. “Six provocations for big data.” (2011) – page 6.