‘Bashing’s’ Datavisualization as Information Intervention

Living in the era of Big Data, data visualization is booming in science, marketing and journalism (( Segel, Edward, and Jeffrey Heer. “Narrative visualization: Telling stories with data.” Visualization and Computer Graphics, IEEE Transactions 16.6 (2010): 1139-1148. )). In this article I want to show that this booming phenomenon is also relevant to politics and social matters. As in that it is being used to enable a saver world. I will do this by discussing the mobile App ‘Bashing’ which is designed to raise community and political awareness for homophobic violence. In order to discuss this app critically, I will analyze it using Lisa Parks’ critique on a data visualization by Google also aimed at raising awareness of violence.

Google Earth’s ‘Crisis in Darfur’

According to Google their project ’Crisis in Darfur’ proves that their Earth software is able to impact what is happening on the ground. It claims to be able to raise awareness and cause intervention through global access to information provided by Google. Lisa Parks is not entirely convinced and therefore writes up a critical analysis of the project in her article ‘Digging into Google Earth: An analysis of “Crisis in Darfur”’ (( Parks, Lisa. “Digging into Google Earth: An analysis of ‘Crisis in Darfur'”. Geoforum 40 (2009): 535-545 )).

During a conference in Washington DC on April 10, 2007 both representatives of Google and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum announced the release of the ‘Global Awareness’ layer in Google Earth named: ‘Crisis in Darfur’. It’s goal? To raise enough awareness for this ‘holocaust’ in order to make sure the world could not ignore it anymore. The second goal was to show the humanitarian possibilities of new information technologies. Parks provides several critiques on this project that put in question whether it really is capable of raising enough awareness and more importantly force people to take action. In this way Parks challenges the notion that change will automatically come through awareness.

Source: Google.com

Firstly the success of this project was measured by the press coverage of it. But did the focus on the success of ‘Crisis in Darfur’ really also meant attention for the real problem in Darfur? According to Parks this attention was more focused on Google and its humanitarian possibilities than on Darfur itself and finding solutions for the violence happening there. Also, instead of showing historical information and structural dimensions, the satellite images of the area just function as an entry point to zoom in on representations of victimized individuals. In this way it tries to affect people into action. But there are two problems: Not only are people in the West increasingly desensitized for these kind of images, because they see them so often, it also conceals the complexity of the violence in Darfur by not focusing on how this political violence came into being in the first place. These complex dynamics of political violence cannot simply be seen and understood. The third problem for this information to be able to intervene immediately, is the temporality of the data. According to Parks ‘Crisis in Darfur’ is an archive of violence, that unfolded while being observed, but without intervention. This reinforces her idea of seeing and knowing without acting. Without providing dates this data does not show when things happened and whether it still makes sense to act on it. Last but not least this project, for Parks, is a form of neoliberalism: Public data privatized by a commercial company in order to get more users for their product. Is this really about helping the people in Darfur or is the goal gaining profit by capitalizing data of world disasters a bigger incentive? The fact that the people in Sudan cannot even access this software, because of US export controls and economic sanctions against Sudan, does not speak for Google’s humanitarian goal of raising awareness and stopping the violence.

Concluding, Parks thus claims knowledge in itself is not always enough for power and that while raising awareness should not be looked at as unnecessary, it will not automatically cause change. In order to be able to cause change more attention for history and where the violence comes from is necessary.

‘Bashing’

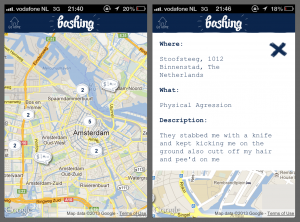

‘Bashing’ is an app designed by Bert Vermeire and developed, launched and advertised in collaboration with advertising agency FAMOUS and the anti-gay-bashing movement Outrage!. Vermeire encountered several instances of homophobic violence himself and following a series of gay-bashing-incidents in the summer of 2011 in Brussels and Antwerp he decided to make this app. The app’s goal is to bring the problem of gay-bashing out in the open and into the spotlight in order to force the community and political world to take action (( Bashing. “Questions and Answers.” Bashing.eu. 2013, 12 March 2013. )). May 30, 2012 this app was also officially launched in the Netherlands by Stichting Vrienden van de Gay Krant (( Verkuil, Martijn. “Bashing App nu ook tegen homogeweld Nederland” Computer Idee: Voor uw dagelijkse nieuws, tips en trucs, forum en downloads. 30 May 2012. 12 March 2013. )). Users of this app can report when they are experiencing or witnessing physical or verbal homophobic violence through the ‘Report Now’ button. One can report whether it was physical or verbal, when, what and where exactly it happened. On the ‘Bash-map’ one can see all the incidents reported by other users on a Google Map. The info page in the ‘Bashing’ app reads (( Bashing.eu. ”Bashing” Famous. 2011. 12 March 2013. )):

Sometimes it seems like homophobia is claiming the streets. And in order to address this problem, people need to know what happens, and where. So instead of having it leave a mark on you, let it leave a mark on our Bash-map! Meaning, if you see or experience something, pin it down. ‘Cause knowledge is half the battle!

Source: ’Bashing’ iPhone App

Firstly, just like Google, the makers of this app claim knowledge is power and awareness will cause action to be taken. Whether this app caused actions to be taken is unclear, the success of this app, until now, is again measured in press coverage on this app and the usage of it. The app now is celebrated because of the potential to change the situation, but did it really cause change? Secondly, like ‘Crisis in Darfur’ this app also zooms in on individual incidents without giving historical information or structural dimensions that caused this kind of violence in the first place. This again conceals the complexity of the problem and relies on the affect of people. But when people see it, do they really take action? Or is this again something people brush off after seeing it? Also even though you have to insert the exact date and time of the incident (probably for some kind of authentication), this does not show on the map, causing the same temporality problem as for Google Earth’s ‘Crisis in Darfur’ map. When did this happen? Is it still relevant to act on it?

What differs from Google is that this really is an activist app made by activists and therefore the commercial goal and capitalizing of disaster is less relevant in this case. Comparing it to Park’s critique on ‘Crisis in Darfur’ it overlaps on certain points and thus also has to face the question whether raising awareness is enough to cause actual change. A very important difference in favor of ‘Bashing’ is that the data is user-generated so it needs active citizens to provide the data. These users thus already are invested in raising awareness and wanting to make a change. Also, ‘Bashing’ itself claims that “knowledge is half the battle!” and therefore acknowledges something else is needed for the actual change.

Let’s take the actual step to change

In conclusion this app is a good step in raising awareness about homophobic violence, but lacks the methods for taking action and background information that shows the complexity of this deeply rooted problem. To cause change the users of this app need more information about how this violence came into being in the first place and better thought out steps to be able to really take action. This app has the full potential to make this world (or at least Belgium and The Netherlands) less homophobic, but has to, next to the visualization of the violence and therefore the raising of awareness, give the community and political world better handles to actually take a stance and act up for change.

Sources: