Visualizing individual measures of emotion

Personal monitoring is becoming increasingly present in many of our daily routines as a conscious and voluntary choice. If you are an outdoor fitness enthusiastic, then you are probably aware of how many miles you ran last month and how much your average running pace has increased. If you are trying to lose some weight, you have probably tried a couple of apps to help you monitor the intake of calories and guide your dietary choices. If getting a good night’s sleep has become a concern, another handful of apps can help you identify your sleeping patterns in order to improve the quality of your rest [1].

Wellness occupies a central position in the quantified self movement [2] as visible by the high number of related presentations included in the 2013 Quantified Self Europe Conference held in Amsterdam this month. But beyond the wellness apps and devices dedicated to fitness, nutrition, sleep and other specific health areas, the trend seems to be moving one step further also embracing wellbeing aspects such as mood and happiness. While wellness indicators are often based on easily traceable and measurable items which can then be transformed into comparable marks, the holistic character of wellbeing incorporates more intangible aspects related to emotional and mental states.

What are the main premises of these platforms aimed at measuring more fleeting and complex internal conditions and what kind of challenges do they face? There are several applications which specifically capture mood, stress and happiness levels (some of which are still in beta phase), but this article will only analyze a few of them as examples of those available in the market [3].

A basic distinction in this area can be made between those platforms which rely on the active user reporting of mood and happiness levels and those which are based on the passive monitoring of physiological signals (such as skin response, heart rate [4], speech tone, posture [5] and facial expressions [6]) as indicators of mental and emotional conditions [7]. Some projects attempt a combination of both in order to obtain more accurate insights while experimenting with possible correlations. The platforms below described fall under the active reporting category.

Active mood reporting

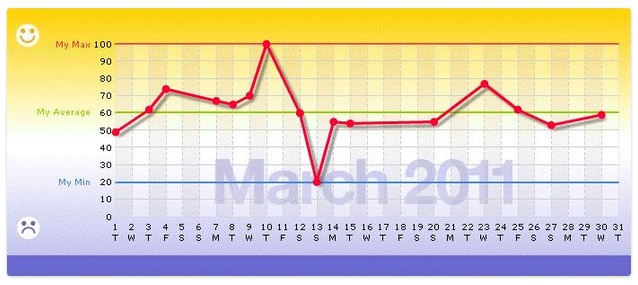

Let us start with Moodscope, an online platform active since 2010 aimed at tracking one’s (baseline) mood throughout a certain period of time [8], which has received a considerable amount of attention from the press but also from the academia and, for this reason, it will be here described more in depth than other tools. Upon logging in the user is prompted to rank his feelings towards 20 different emotional states (based on the Positive and Negative Affect Scale proposed by Watson et al in 1988) through the means of double-sided playing cards. The process is relatively quick and simple and provides access to a mood score graph (see image 2) which becomes increasingly populated as the user returns to the website, ideally on a daily basis, to register his mood.

The novelty which initially differentiated this tool from other ones with similar goals is the “buddy” system: the user can opt to choose between 1 to 5 other trusted users (family members or friends) with whom he will share his daily scores. The assumption is that the awareness of this external monitoring feature leads to more positive results – a specific phenomenon of the Hawthorne Effect.

In 2012 an academic research was published based on the results of 2 focus groups using Moodscope over a period of 3 months. Even though the users’ reaction to the tool was not unanimous, the major challenge that it might face seems to be one related to the motivation level. For the users who are not gathering any new insights about their emotional condition, it is very difficult to keep registering their mood on a regular basis as the continuous repetition of the monitoring may seem purposeless. As for the “buddy” feature, the perceived burden can lead some users to reject its usage from the start and others to moderate their responses. In a 2010 study conducted by Moodscope itself based on the gathered user data, it is shown that users who utilize the “buddy” system have continuously better scores than the ones who do not use it due to the prompt social support intervention, but one can question to which extent these results may incorporate the bias of a pre-existing strong(er) social network for the users achieving higher results.

Still, the results from this independent research recommend Moodscope as a useful tool for users who are experiencing mood issues for the first time and as a complement for therapy or counseling (while not functioning as a replacement). Some users who experience higher mood variability find the results useful as they can shed light into causal relations for negative dispositions and also trigger a more immediate and efficient response when necessary.

Another project based on the same mood monitoring premises and psychological model as Moodscope is one integrated in the mobile platform Ginger.io. The main difference in this case is that the active data gathered via surveys is used in combination with passive data automatically captured (such as communication statistics on duration of calls, dialed numbers or length of text messages) so that the correlation between both types of data would enable the accurate prediction of, for instance, certain moods in the future just based on passive data [9].

For those users who would like to have access to some type of mood insight but would prefer to restrict the time span of the monitoring process, Track Your Happiness is another alternative which only requires a limited number of measurements (50) to produce a report. The user initially selects how many times per day the happiness survey (containing the same amount of core questions plus a group of questions which varies every time) should be sent. Once the final report is complete, the user can opt to schedule another “mood snapshot” within a period of time of up to one year.

A more visual, and perhaps lighter, alternative to language driven mood tracking is color association. This is the case of MoodJam, a platform released in 2006, which allows the user to introduce one adjective descriptive of his mood and then select a matching color [10]. There is no imposed or suggested schedule for this activity and the results can then be publicly available in a multicolor community mood gallery. A similar color matching logic is followed by the MoodTracker iPhone app [11] where users can additionally set up their own grading scale and also associate a location to the mood data.

Other applications emphasize the social aspect of mood tracking transforming it into a collective activity. MoodPanda is probably the best example to illustrate that concept since it allows, for instance, the comparison between the individual mood and the global mood, as well as it provides information on what makes other users from all over the world happy or unhappy, among other features which actively promote the interaction between community users such as “giving hugs” [12].

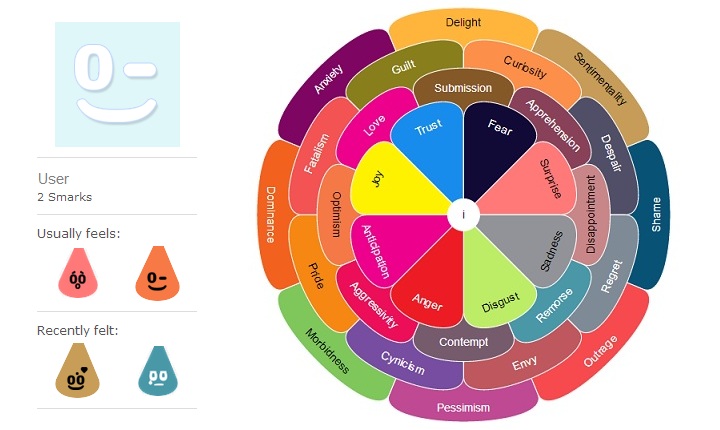

Expereal, an iPhone app which works in association with a Facebook account, also highlights the social aspect of mood tracking (using a 1 to 10 scale, colors, location, photos and tags) but within a more intimate network of selected friends instead of the global community composed mostly by strangers [13]. Within the same category, the online platform MySmark incentivizes sharing feelings through a colorful “rose of emotions” and the iPhone app GottaFeeling provides a stripped down version of the process.

One happiness measure does not fit all

Mood tracking and happiness monitoring are not linear and straightforward processes. Users who are concerned with this type of self quantification can be motivated by different reasons: some experience high mood variability and may suffer from disorders such as bipolarity while others may merely want to gain additional insight into aspects which might interfere with their mood or situations which trigger higher or lower levels of happiness. Many claim that mood and happiness, even though they can be related, are indeed different conditions and therefore should not be confounded.

The assessment methodology is also far from consensual since there is no unique psychological model to measure emotional states. Just to cite one example, some theories claim that happiness is the opposite condition to sadness (so these items would be the two extremes of one spectrum) while others defend that happiness and sadness are emotions which can coexist just like other positive and negative feelings. The premises of each theory will inform distinct psychological models which, in turn, will originate separate results.

Furthermore, not all methodologies are suitable for a specific individual as they might fail in revealing personal subtleties or may overemphasize some elements which are mostly irrelevant to that person. Different individuals experience emotions differently and this is probably the reason why some users have forged their own approach in creating a customized measure of happiness [14].

With such a wide variety of tracking options, it will be interesting to witness if in the near future more people feel compelled to monitor their mood and happiness and in which manner: actively or passively; publicly or privately [15]. And, more importantly, if the winning platforms will deliver to the users the insights required to an increased level of self-awareness ultimately leading to the desired self-development.

[1] This article from March 2013 provides some statistics regarding self-tracking. [back to main text]

.

[2] More general information about the quantified self movement can be found on this blog post. [back to main text]

.

[3] Solutions used exclusively in clinical environments for medical purposes are not considered in this article. [back to main text]

.

[4] See emWave2 as an example of a device in this area. [back to main text]

.

[5] See LumoBack as an example of a device in this area. [back to main text]

.

[6] On the field of facial expressions, you can watch Nancy Dougherty’s presentation on “Technology for Mindfulness” during the Quantified Self 2012 Conference at Palo Alto, California. [back to main text]

.

[7] For an overview of the technology on this domain, watch Matt Dobson’s presentation on “Quantifying Emotions” during the Quantified Self London Meetup in October 2012. [back to main text]

.

[8] Founder Jon Cousins gives his personal account on how the platform was born in this video. [back to main text]

.

[9] Watch Ryan Hagen’s presentation on “Tracking Mental Health with a Smartphone” during the Quantified Self Boston Meetup in October 2012. [back to main text]

.

[10] Watch Ian Li’s presentation in the Quantified Self Pittsburg 2011 Meetup to learn more about the platform. [back to main text]

.

[11] For additional information on the app, watch Marie Dupuch’s presentation on Quantified Self New York 2011 Show&Tell. [back to main text]

.

[12] For more information, read an interview with co-founder Ross Carter. [back to main text]

.

[13] For more information, read an interview with founder Jonathan Cohen. [back to main text]

.

[14] As a reference on this topic, watch Konstantin Augemberg’s presentation on “Testing Three Models of Happiness” at the Quantified Self New York Show&Tell in February 2013 and Erik Kennedy’s presentation on “Quantifying Happiness” at the Quantified Self Seattle Show&Tell in October 2011. [back to main text]

.

[15] Or, as put by Alexandra Carmichael in this article, if they will become “mood nudists” or “mood monks”. [back to main text]