New ROBOTICS: The Genesis of Artificial Creativity?

1942. Isaac Asimov writes “Runaround”, in which he promulgates the Three Laws of Robotics:

1. A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

2. A robot must obey the orders given to it by human beings, except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

3. A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

Boston Dynamic’s Big Dog (http://slice.mit.edu/)

The birth of Artificial intelligence dates back to 1898, with the development of the first remote control machine in history, which Nicola Tesla , its developer , envisioned to serve as a robotic pack mule to accompany soldiers in terrain too rough for conventional vehicles. The birth of AI was deeply utilitarian.

Over a century later, in 2014, robotics has reached the new height of BigDog , a concept which is funded by the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). DARPA’s design, like Tesla’s long before it, remains one in which—quite simply—the robot’s hands get dirty instead of ours. And in the ever-increasing technologization of warfare, the loss of their ‘life’ takes the place of human casualties.

Between Tesla and DARPA, however, there is a bright side to Robotics. They are helping push human development and lifespan further in the areas of applied medicine, heavy industries, secretarial work, telecommunications and recently in Publishing & Writing—or the so called Automated Journalism.

Consistent across each prior development of Artificial Intelligence is the essence of utilitarianism. Historically, we have made robots in order to use them – to use their bodies and their labor, in a simple substitution, in place of ours. The ‘Intelligence’ in this AI is an intelligence of functionality: human functions are replicated or improved upon in robot functionality. But what if we could take robotics past the threshold of use?

Robots City is a new Amsterdam start-up which aims to bring Robots one step closer to the public, by providing an innovative and entertaining forum where human life can intersect with robot ‘life.’ No longer are Robots only accessible to those who work for robotics laboratories or defense industries. In its debut performance, the Robots City Amsterdam show produced the longest duration Robotic Art Show in the history of robotics.

Robots City Amsterdam Show (Martirosov’s personal archive)

Robots City, a promising start-up just founded in September 2014 – a few days before this blog was published – claims to penetrate the CREATIVE Industry with the use of the most advanced Robotics technologies: the latest generation of Nao and Titan robots.

Robots City is an unorthodox, raw blend of imagination, innovation, and madness, in which ART fuses with ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE like never before, in every act, in any application.

Jacques Martirosov, Robots City Creative Director

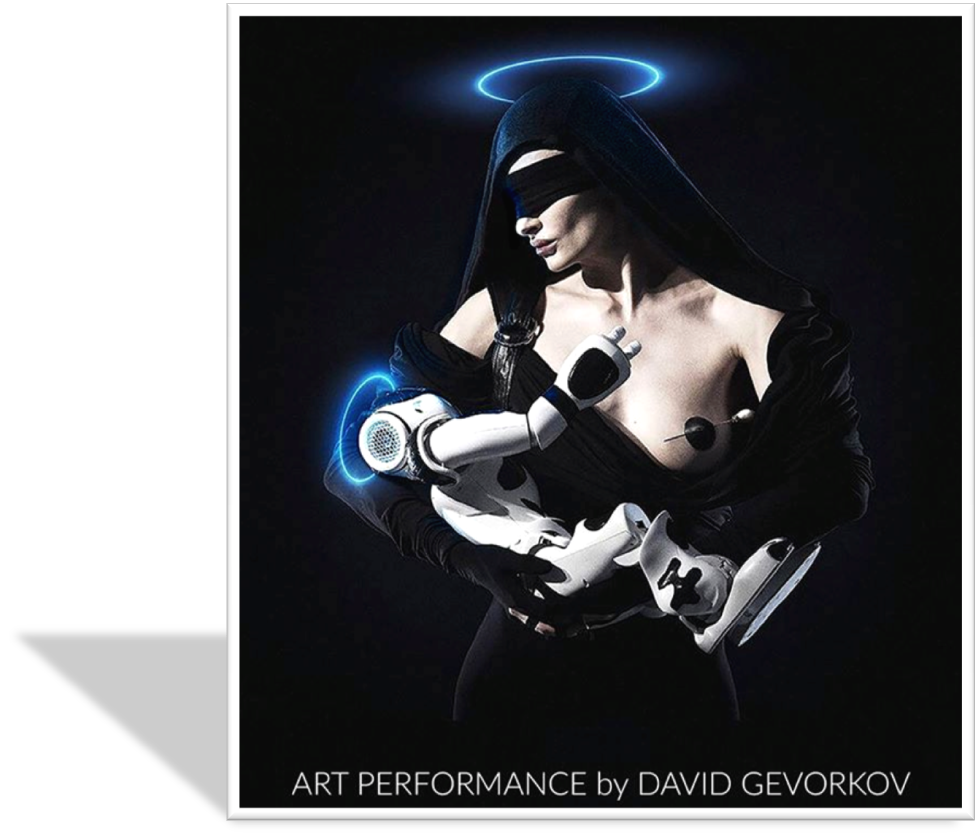

Martirosov also revealed that Robots City’s upcoming creative use of robotics will show itself in Fashion Week Paris, September 2014, covering the Haute Couture of the famous Russian Fashion Designer David Gevorkov. In this show Robots will prophesy the new era of fashion as Jesus birthed a new religion.

Robot City forcoming event (Martirosov’s personal archive)

At later phase, Robots will perform as DJs in big clubs (like Le Carmen – in Paris) , often competing with human DJs; another creative application of Robotics.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is the intelligence exhibited by machines or software where an intelligent agent is a system that perceives its environment and takes actions that maximize its chances of success (Russell and Norvig). In this sense, machines are programmed to use skills like Problem solving, Deduction, Induction, Learning, Imitation, Trial and error, Heuristics and or Abduction, which by default are NOT central elements of creative processes, but rather only logical reasoning processes (Harnad). Creativity – which is considered by most to be an essential component of human intelligence (Boden)- is commonly defined as the ability to produce work that is novel (original, unique), useful, and generative (Sternberg and Lubart)

In the case of Robots City, Artificial Intelligence is actually used in a way as to promote Creativity in the commercial Art world. Robots are designed to participate in creative processes and dynamically enter the creative industries. In this case, Robots become the source of inspiration for creative humans; a state that still obeys the “Laws of Robotics”, yet also brings to the forefront the issue of ‘Artificial Creativity.’ (Wallisch)

In a world where AI is constantly being developed based on “learning from the brain” and-or trial and error(Bhasin et al.), AC is also prone to this development, in a sense that Robots can gradually perform creative processes and eventually become as creative as human.

For humanity, the central question regarding Artificial Intelligence has always been, “What if they become smarter than we are?” (Frankish) Scenarios of near-omniscient robots and computers continue to profuse science fiction literature and film even today.

With this new instantiation of Artificial Creativity, a new question knocks on humanity’s door:

What if Robots become more creative than Humans?

Have we even begun to imagine what is at stake in this question – if human creativity may be surpassed by another source? It may be our human tendency thus far in history to assume that no artificial source of intelligence could be nearly as creative as we are because it is our feeling selves that we see as central to our creativity. What if, for artificial intelligence, there is some other source? Or, perhaps stranger, what if robots do begin to feel? What, then, might be at stake?

References

Bhasin, Harsh et al. “Study of Factors Affecting Artificial Creativity.” N.p., n.d. Web. 15 Sept. 2014.

Boden, Margaret A. “Précis of The Creative Mind: Myths and Mechanisms.” Behavioral and Brain Sciences 17.03 (1994): 519–531. Cambridge Journals Online. Web.

Frankish, Keith. The Cambridge Handbook of Artificial Intelligence. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014. Print.

Harnad, Stevan. “Creativity: Method or Magic?” First. University of Southampton, 2008. Print.

Russell, Stuart, and Peter Norvig. Artificial Intelligence A Modern Approach. Second. New Jersey: Pearson Education, 2003. Print.

Sternberg, Robert J., and Todd I. Lubart. “Investing in Creativity.” American Psychologist 51.7 (1996): 677–688. APA PsycNET. Web.

Wallisch, Pascal. ARTIFICIAL CREATIVITY. Chicago: University of Chicago, 2008. Print.