Could Snapchat’s new feature challenge Facebook’s dominance in terms of trust and privacy?

What’s the next Facebook or is there one? Ask many, including John D. Sutter (2012), who suggests that this question is not only wishful thinking, but an increasingly likely reality. Jamie Turner argues that although Facebook is still “king of the hill”, there are a lot of threats coming out in the near future as the world’s largest social network constantly faces competition (see the video below).

As this video went live on YouTube in 2012 and Facebook’s power has not been threatened since then, is it even possible in the near future?

Facebook facing lack of trust

Some writers, including Saeri and Ogilvie (2014), point out that Facebook is losing popularity over privacy concerns. Most scholars seem to agree with this statement. According to studies conducted by Chang and Heo (2014), over 70% of respondents do not trust Facebook with their personal information and most of them do not want to see their whole life being exposed to everyone.

Li (2014) highlights that the majority of Facebook users want to connect with family and friends, but they do not necessary want all of their private information out there for the entire world to see. In this case, what application or social media platform would challenge Facebook’s dominance? As Poltash (2013) points out, the privacy-related Snapchat smartphone application and its new feature could do that.

Snapchat’s self-destructing messages

The image of Snapchat taken from Snapchat.com

Snapchat is a smartphone application which allows its users to share time-limited videos, photos and video chats. It was invented by Bobby Murphy and Evan Spiegel in 2011, students of the University of Stanford, who wanted to create something that could transmit the emotion that a person might be wishing could be sent with a text message (Potash 2013).

“Snapchat creates a freedom for people around the world to just be themselves, sending 400 million snaps daily,”

says Spiegel (Time, April 23 2014).

What’s so phenomenal about Snapchat then and what’s its new feature? Users used to view snaps for up to 10 seconds, and then it “disappears” from the screen – unless they decide to keep it, such as with a screenshot or separate camera (Snapchat guide for parents, 2014). The new feature allows users to see snaps only for 3 seconds and it is impossible to retrieve it after the time is up. Ege (2014) points out that such a short period of time of snaps being exposed to users make them praise its high level of privacy and low performance anxiety pressure (comments are not allowed) even more which Facebook is often accused of by scholars and Internet users. Moreover, thanks to improved conversation features on Snapchat, chats are more like real conversations as users need to be present online to see the snapshot notices. In this way, interactions between users are more natural, more spontaneous and more fun.

“It’s a platform where they can communicate and have fun without any anxiety about the permanence. You hear about kids not getting jobs because of what’s on their Facebook page,”

explains Curley (TechCrunch 2013).

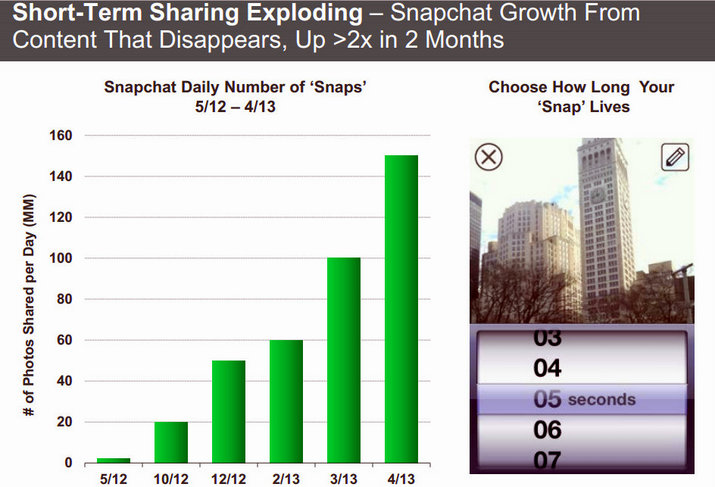

Snapchat’s phenomenon has increased dramatically, highlights Roesner et al. (2014, p.1). In 2013, the smartphone application was used by over 8 million adults (Forbes 2013) and there were over 350 million “snaps” sent daily (Koh 2013). As the graph below illustrates (Meeker 2013, p.15), there was a significant growth of photos shared per day on Snapchat between 3/13 and 4/13.

Impressively, after the new feature was introduced in August 2014, there were over 60 million monthly active users – 52 million more than in the previous year (Bennett 2014).

Worrying misuse of Snapchat

While undoubtedly Snapchat seems to be more secure in terms of privacy than Facebook amongst the users of both Social Media tools, the question arises how much privacy we really have with electronic messaging nowadays?

Roesner (2014, p.10) illustrates in her survey that over 25% of teenage users of Snapchat use the messaging application for “sexting” and 14.2% admit to having sent sexual content via Snapchat at some point (p.4). Furthermore, the research conducted in summer 2013 showed that almost 50% of young girls and boys were using the Snapchat in the UK to send naked images between friends (Walker 2013). These statistics are a big concern not only for parents but also for the young generation of smartphone applications. Furthermore, even if you couldn’t take a screenshot of your phone to save a photo or find the video in memory, you could still use a second device to capture the same imagery. The receiver of the message could be in a crowded room and display your message to everyone who dared to look. And considering the receiver has to intentionally save or find the message, it sounds like there is a trust issue to begin with. So ultimately, can you really expect a digital messaging platform to keep your interactions private? License (2014) argues that any message receiver using Snapchat can display the content to friends who are in the same room while opening the message.

Would you trust Snapchat’s new feature more than Facebook? Share your thoughts in comments.

References:

Bennett, S. “Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Pinterest, Vine, Snapchat – Social Media Stats 2014.” Blogs.wsj 2014. Web. 12 Sept. 2014.

Chang, Chen-Wei, and Jun Heo. “Visiting Theories That Predict College Students’ Self-Disclosure on Facebook.” Computers in Human Behavior 30 (2014): 79–86. ScienceDirect. Print.

CNN. “What’s the next Facebook (or is there one)?” CNN What’s new, 18 May 2012. Web. 7 September 2014.

CNN. “Will “Tagged” emerge as New Facebook?” CNN, 2012. Web. 8 September 2014.

Constine, Josh. “Kids Love Snapchat Because They See Facebook Like Adults See LinkedIn.” TechCrunch 2013. N.p., n.d. Web. 11 Sept. 2014.

Ege, R.K. “Secure Trust Management for Mobile Platforms.” 2014 International Conference on Computing, Networking and Communications (ICNC). N.p., 2014. 381–385. IEEE Xplore. Print.

Forbes 2013. “Is Snapchat Raising Another Round At A $3.5 Billion Valuation?” N.p., n.d. Web. 11 Sept. 2014.

Koh, Yoree. “Snapchat Sends 350 Million ‘Snaps.’” WSJ Blogs – Digits. N.p., 9 Sept. 2013. Web. 11 Sept. 2014.

License, New Media Drivers. “Snapchat – How Much Privacy Can You Reasonably Expect? | New Media Drivers License Seminars.” N.p., 13 May 2014. Web. 11 Sept. 2014.

Li, Xiaoming. “Interpersonal trust measurements from social media interactions in Facebook.” Montana State University (2014). Print.

Meeker, Mary. “2013 Internet Trends.” N.p., n.d. Web. 12 Sept. 2014. Print.

Poltash, Nicole. “Snapchat and Sexting: A Snapshot of Baring Your Bare Essentials.” Richmond Journal of Law & Technology (2013): 1–24. Print.

Roesner, F. et al.” Sex, Lies, or Kittens? Investigating the Use of Snapchat’s Self-Destructing Messages.” University of Washington, Computer Science & Engineering 2 Seattle Pacific University, Mathematics (2014). Print.

Saeri, Alexander K. et al. “Predicting Facebook Users’ Online Privacy Protection: Risk, Trust, Norm Focus Theory, and the Theory of Planned Behavior.” The Journal of Social Psychology 154.4 (2014): 352–369. Taylor and Francis+NEJM. Print.

Time. “The World’s 100 Most Influential People.” TIME.com. N.p., n.d. Web. 10 Sept. 2014.

Walker, Tim. “The 23-Year old Snapchat Co-Founder and CEO Who Said No to a $3bn Offer from Facebook.” The Independent. N.p., n.d. Web. 10 Sept. 2014.