On Grindr: is our pocket the new closet?

First written in January, 2014.

Grindr, the rising star of the Apple Store; so much ink has been spilled over this app. When fans aren’t writing books, praising its various merits or licking the balls of its founder, they now produce webseries or even work on musicals, as proudly announced recently.

But even more surprising than its success among gay men is the app’s reputation among straight people: “You’re on Grindr? Cool! Any cute guys around? Let me help you pick one!” is what I often hear at parties when, in a moment of boredom and, as a half-conscious gesture, I start scrolling around. This enthusiasm is so widely spread that the device regularly pops up in many and varied media sources such as Slate, Wired, the Huffington Post, the Guardian, Le Monde, Die Welt, HBO’s Girls, and the list is ongoing… Seriously, what’s with all the noise?

Ok, I can get that at first sight, Grindr seems rather magical: it’s a classic extension of Man, a technical gaydar that reveals homosexuality all around, sometimes unveiling secrets that my instincts haven’t perceived. If Grindr has been banned in Turkey as a “protection measure”, it’s precisely because it truly facilitates male encounters. But besides the excitement, shouldn’t we be more critical?

Grindr, a sex market?

First of all, the app conveys a very capitalistic view of sexuality and looks more like a tacky marketplace than a bar or a club. By looking at its (limited) profile interface, Grindr definitely focuses on bodies more than on personalities. Rather than tastes or hobbies, it pushes men to disclose ‘age,’ ‘height,’ ‘weight,’ ‘body type,’ and ‘ethnicity.’ These minimal profile settings added to the localization features emphasize their transformation into merchandises, locatable and consumable. As this anonymous Australian blogger dramatically denounces: “we have become a consumer product. We are the iGays. We have lost our souls. And we don’t even know it.”

More than products, the app transforms users into consumers: thanks to the payable XTRA version and its filters, I can Grind tailored guys, being given more options than when buying a new iPhone. The categories then make more sense: a way for purchasers to better filter guys rather than a tool for members to express their identities.

Grindr, vector of oppression?

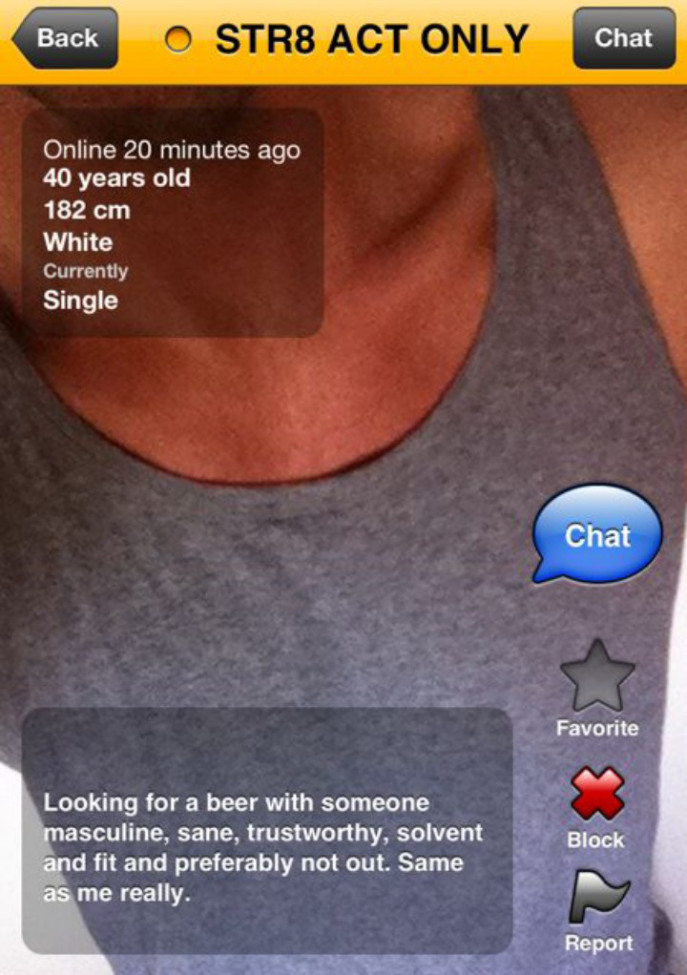

If I like Grindr for one thing, it’s how it daily illustrates how heterogeneous homosexuals can be. Yet, the app remains famous for its typical ageist, racist and homophobic profile descriptions.

In addition to confirming that the gay shelf life surely can’t exceed 35 (be it for young guys ignoring anyone slightly older as well as creepy forty-somethings requiring “under 25”), the device enables some to express their sexual racism freely, rejecting or fetishizing particular ethnicities. Instead of encouraging us to question our sexual preferences and (as this half English, half Japanese dude does) the potential stereotypes they are issued from, Grindr pushes us to be always pickier and to filter others according to their skin colour.

The platform also exemplifies how many gay men so strongly inherited heterosexist norms. Guy Hocquenghem, a radical queer theorist known for his iconic “our asshole is revolutionary” motto, already reflected on this topic in Screwball Asses, where he strongly criticised the very binary gender roles division that some gays hold on to, stating quite straightforwardly: “Active, passive, old bullshit” (34). The incredible amount of dudes who start their conversations with a gross “top or bottom?” as mere introduction should definitely read his prose (which, though published in 1972, remains very accurate and a pretty fun reading – what a shame, isn’t it, that HIV put such a precocious end to Guy’s revolutionary aspirations!)

Our guy disapproved their tendency to “program homosexuality just like a heterosexual imagines it can be experienced, the same way he would speak of it or fantasize it, with males on one side and females on the other: here the bears that desire a failed man instead of a woman, here the flaming queers that desire a bear.” (9)

His last sentence, however, only party applies to Grindr where, if (too) many label themselves “straight-acting” (the gay-but-not-faggot, here, proudly advertising his normality), not so many desire camps… rather the contrary: requests as “MASC ONLY” or “NO FEMME!” flourish on the app, basically saying to queens to go fuck themselves and feeding them their slice of homophobia of the day, which on a gay app is regrettable. And “straight-acting”, guys… seriously?

By the way it presents men, creating a mosaic of faces and bodies quickly evaluable and comparable, Grindr emphasizes the “Adonization” of an already cruelly competitive gay culture where, on top of the pyramid, stands the white, masculine, fit, young, urban and handsome guy. It tends to exclude all of those whose appearance don’t match dominant beauty norms, sometimes rather violently.

That those who have themselves been subject to oppression and otherisation might so eagerly reproduce them on their kind remains a mystery to me. But hey, the human race is a dumb one, and homos are no exception.

Grindr, the gay ‘cruising machine’?

Despite that, Grindr remains super addictive, sometimes rightfully described as the “the gay slot-machine”. This expression reminds me of Hocquenghem, who discourses on the homosexual “cruising machine” and this libertine culture that is, in his mind, only the fruit of a heterosexual society, and of capitalism: “a couple is something homosexuals do not like, something they almost never like; it is even what they hate or fear the most” (49) he says, before asking if fags don’t actually dream of coupledom “just as secretly as the bourgeois desire to be Casanovas” (50). His hypothesis applies well to Grindr where, if one believes our Australian blogger, many “deny their true desire” and pretend to want NSA fun not to look needy and desperate, even though they actually are.

The cruising machine, writes Hocquenghem, “instead of being madly in love with what is present, desires what is absent, always desires the next object, it constructs itself on the establishment and sacred assumption of lack, according to the absolute criteria of consumption” (51). Is this why, despite an upcoming date with a cute guy I like, I find myself Grinding around without knowing what I’m looking for, starting pointless conversations I actually never finish? Is Grindr nothing but an iPhone manifestation of Hocquenghem’s cruising machine?

Grindr, back to the closet?

In addition, the device also challenges issues such as visibility or social recognition. If Grindr has often been described as “the biggest gay bar on earth”, it remains nonetheless an invisible, discreet gay bar. “Discreet”: another Grindr category, a word that some even emphasize on in their profile. Discreet… or ashamed?

Far from the idea of me judging those who prefer not to expose their sexual or affective orientation to the cruel look of others. But still, Grindr’s logo, this creepy black mask, leaves me with a weird feeling and evokes to me Hocquenghem (again). In the introduction to his book, the author follows a fellow invert into Paris’ École des Beaux-Arts’ toilets, a shady corner where “half a dozen bodies, anonymous in the dim light, are enlaced […] in what complex circuitries one cannot immediately decipher”. The scene enrages him: “I know how many queers only have toilets in which to touch each other. It depresses me that those who have decided to come out of hiding continue to project their excitement in the miserable places that the system condescends to allow them” (4). Could Grindr, with its shadowy torsos, its masked invisible users, be our modern toilets of the Beaux-Arts, a place where faceless shameful men would look for discreet encounters? Could our pocket become the new closet?

Not only for the catchy rhyme do I allow myself the use this distasteful expression; the metaphor also seems pertinent. Even without being so pessimistic, we can agree with Roderic Crooks that Grindr “connects to older patterns of gay socialization” and makes us travel back in time: “the tell–tale sign recognizable to insiders over the showy displays of identity, [Oscar Wilde’s] green carnation over the rainbow flag”.

Grindr, a killer of community?

New media, according to him, negatively impact queers’ presence in the physical city and the number of meeting places. Who needs gay clubs when one is always open in our pocket?

Worst, they even “impede the progress of gay culture and progressive politics” without advancing one of the main purposes of queer heterotopias, “the affective aims of alternative community.”

It’s true that the app, by the way it enables connections among users, hardly favours the establishment of collectivity, a spirit of solidarity: group conversations remain impossible (except when chatting with a couple looking for a threesome) and, ironically, the few online communities around the app are often derisive. One could almost believe that if someone had wanted to kill any form of social demand among male homosexuals, they couldn’t have done it any better…

More seriously, the case of Grindr illustrates well some of queer politics’ paradoxes, with desire for banalisation on the one hand and refusal for assimilation on the other. And though humanity will most likely survive the closure of a few sleazy bars, the risks of normalization and demobilization deserve a moment of wonder.

Because queer subcultures are as numerous as they’re heteroclite, they have (almost) always been tied to transgression, creative innovation and social critique. They deserve to be celebrated, discussed, challenged, reinvented; they remain a refuge for those who feel truly different and refuse to worship the white, masculine, consumerist and boring gay-but-not-faggot.

Because while I docilely dial on my green iPhone 5C and flirt with random guys, my ass comfy on my couch, I forget about the world around me and the many challenges still facing most minorities.

Grindr, nothing but a draft?

The success of Grindr, mostly, shows how much we need technical devices to facilitate encounters and realize possibilities, and allows us to hope for more.

Rather than sticking to current models of locative media, one can think of new ways to use such technologies to enable connections between digital and physical spaces. To produce some that embrace the diversity of queer identities and where everyone has a place.

I had the luck, a few years ago, to regularly dance in that famous German club so many people chatter about, a true “heterotopia of deviation” (to quote good old Michel Foucault) with its own codes, values and rules. Inside these massive concrete walls is a true space of liberty, a tiny world where oppression usually stays out. I’m grateful I was able to be part of this community and, when swallowed by that grey monster again and recognizing its indescribable smell, I feel like home. I’m thankful some things don’t change, glad to know they still exist, and that down there people keep dancing, meeting and not behaving. I realize how precious such places are, and hope that new media, instead of make them disappear, will strengthen the communities around them: diverse, colourful, vibrant crowds.

Rather than Grindr, I wish for a pocket Berghain.