Throwing a Life Vest at Humanity

Alan Kurdi’s Photo. A photo of a boy, lying facedown on a Turkish beach, sporting a little red shirt and velcro shoes. This was the image that circulated the world wide web last week, becoming the latest example of the role of New Media in current socio-political landscapes. Alan Kurdi was only 3 years old when he, his 5 year old brother, and mother drowned in their attempt to reach Greece. The photo of his little body washed ashore, and the tragic story surrounding it, gave the world a glimpse of the desperation of displaced Syrians and other troubled nations.

The so-called “Migrant Crisis”. Just when European policy makers were hardening their stance against the so-called “European Migrant Crisis”, the photo was considered a stark wakeup call for them. Just before the photo’s circulation, Hungary “shut down rail traffic for migrants heading west” and had begun fortifying a wired fence on the Serbian border. To name a few more examples, the UK and the Netherlands had also expressed intentions of tightening policies against “migrants”.

The general public also seemed indifferent and even threatened by the influx of displaced Syrians (among other peoples), thanks to news media terms like “migrant crisis”, “refugee crisis”, “economic migrants” and “asylum seekers”. This is one of the latest examples of Media Framing, wherein the media selects “some aspects of a perceived reality and makes them more salient in a communication text” (Entman, 1992, p. 52). With regards to immigration Thorbjørnsrud says,

“… the media sustains a distorted, problem-oriented image of immigration by employing metaphors, images, and symbols that create stereotyped portrayals of immigrants or depict immigration as a threat” (Thorbjørnsrud, 2015, p.776).

With EU policies and public sentiment against them, the situation couldn’t get any worse for displaced Syrians. That is, until the photo of Alan Kurdi, amplified by social media, awakened the world’s conscience.

The cry that was heard.

‘ “Three-year-old Aylan Kurdi was lying lifeless face down in the surf, in his red t-shirt and dark blue shorts folded to his waist. The only thing I could do was to make his outcry heard.” It was that moment, Demir added, that she took the shot.’ (Doǧan News Agency)

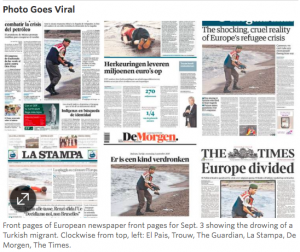

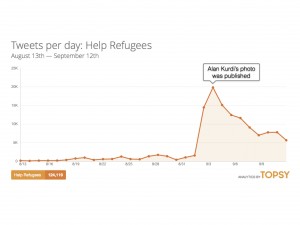

But not even the photographer behind the photo, Nilüfer Demir, foresaw just how loudly the cry would be heard. The photo was published by news websites, amplified by social media, and became a viral sensation overnight.  Hashtags like #HumanityWashedAshore, #KiyiyaVuranInsanlik and #DrownedSyrianBoy, generated conversations and spread the image. Artists also used these hashtags to share original cartoons that expressed sympathy and provoked discussions around the issue (Frisk, 2015). In the meantime, #RefugeesWelcome and #DontLetThemDrown served as public campaigns and channels through which people could translate their concern into actual donations.

Hashtags like #HumanityWashedAshore, #KiyiyaVuranInsanlik and #DrownedSyrianBoy, generated conversations and spread the image. Artists also used these hashtags to share original cartoons that expressed sympathy and provoked discussions around the issue (Frisk, 2015). In the meantime, #RefugeesWelcome and #DontLetThemDrown served as public campaigns and channels through which people could translate their concern into actual donations.

Outside of social media, the photo’s online proliferation fueled public petitions in favor of the displaced persons in both the UK and Canada. According to the Wall Street Journal, “an online petition urging Prime Minister David Cameron to accept more asylum seekers surged to more than 300,000 signatures from 40,000 a day earlier” (Parkinson and George-Cosh). It also made an impact in fundraising, with the Migrant Offshore Aid Station (MOAS) raising €250,000 in less than 24 hours following the photo’s release (Merelli). Global search trends also indicate that how to help out was suddenly a topic for discussion.

Photos have been known to cause social change in the past, but the speed by which this photo yielded positive results is remarkable. Some say social media activism, or “slacktivism”, is a passive form of activism that doesn’t really wield change. However, two strengths of social media activism are evident; speed and the ease of taking action (Merelli). Now, anyone can start a debate, influence other’s opinions, volunteer, or donate to a cause with just one click.

Taking a step back. The strange thing is, Alan Kurdi was not the first to perish in the water. But why didn’t the first few thousand deaths evoke as much sympathy or change?

A psychological phenomenon called the “Collapse of Compassion” may explain this. Cameron and Payne wrote that “as the number of people in need of help increases, the degree of compassion people feel for them ironically tends to decrease” (2010, p.1). So while past news articles covered mass movements and large-scale tragedies in relation to the crisis, this story zeroed in on an individual. Moreover, the lack of violence or anything out of the ordinary made it easier to imagine that the boy in the photo could be a son, brother, or nephew.

“Part of what touched people about this picture is that it is shocking but it isn’t graphic. He isn’t maimed, he isn’t bloodied, he looks like he could be sleeping except for the context. He looks like he could be any of our children” (Gunter).

Alan’s story humanized the crisis for the world. After the photo, people no longer saw masses of people, but rather human beings.

Is social media the solution to media framing? The social media landscape gives abundant opportunities to reach out to others. You can sign a petition, be part of a campaign, donate to a cause or sign up as a volunteer. More importantly, Alan Kurdi’s photo demonstrated the power of social media to influence public sentiment towards an issue.

But for us to really solve anything, it will all boil down to choice. Our choice of words, and what we choose to share, can go a long way when we’re online. It could also be as simple as choosing to see what is merely in front of us:

“No one puts their children on a boat unless the water is safer than the land” (Friedman).

References:

Cameron, C. Daryl, and B. Keith Payne. “Escaping Affect: How Motivated Emotion Regulation Creates Insensitivity to Mass Suffering.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 100.1 (2011): 1–15. Print. American Psychological Association.

Doǧan News Agency. “Photographer of the World-Shaking Picture of Drowned Syrian Toddler: ‘I Was Petrified at That Moment.’” Hurriyet Daily News 3 Sept. 2015. Web.

Entman, Robert. “Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm.” Journal of Communication 43.4 (1993): 52. Print.

Friedman, Uri. “The Black Route of Death From Syria.” The Atlantic 28 Aug. 2015. The Atlantic. Web. 14 Sept. 2015.

Frisk, Adam. “IN PHOTOS: World Mourns Drowned Syrian Boy Alan Kurdi – National | Globalnews.ca.” Global News 3 Sept. 2015. Web.

Gunter, Joel. “Alan Kurdi: Why One Picture Cut through – BBC News.” BBC News 4 Sept. 2015. Web.

Merelli, Annalisa. “Your ‘slacktivism’ Really Does Help the World – Quartz.” N.p., 6 Sept. 2015. Web.

Parkinson, Joe, and David George-Cosh. “Image of Drowned Syrian Boy Echoes Around World.” Wall Street Journal 3 Sept. 2015. Wall Street Journal. Web.

Thorbjørnsrud, Kjersti. “Framing Irregular Immigration in Western Media.” American Behavioral Scientist 59.7 (2015): 771–782. Print.