Post Mortem

How to Quit Facebook (or Make It Quit You)

At the start of 2015, it seemed that Facebook was losing users, especially among younger people (Lang). According to an article in the Washington Post, teenagers are leaving the ‘uncool’ social media platform, while parents are starting to take over (Lang). Increasingly, teenagers are moving to other social media platforms, such as Snapchat (Lang). However, Facebook still managed to reach one billion daily users in August. Mark Zuckerberg posted an announcement on his own Facebook-page stating that “on Monday, 1 in 7 people on Earth used Facebook to connect with their friends and family”.

This demonstrates that even considering or trying to quit Facebook can be a challenging task, whether you actually leave or not. For example, Jessi Hempel – a writer at WIRED – took a social media sabbatical, and she admits to have been cheating during her time off from Facebook. Other bloggers confirmed this struggle and described Facebook as a bad habit that they needed to break: “It turns out my Facebook addiction was just a (really) bad habit. By interrupting the habit, I might have broken the cycle” (Kim).

Facebook also intentionally makes it hard to delete profiles, for example through their user-friendly interface (Gehl 113). Even when users finally decide to leave, disconnecting is not easy. Deleting an account is very time-consuming, as a considerable amount of buttons stand between users and their goal (Karppi, Disconnect.Me 77). Instead, users get the suggestion to merely deactivate their account. This way, the data that users have provided remain intact and can still be used by Facebook (Karppi, Disconnect.Me 77), and users are easily persuaded to log in again and pick up where they left off. Furthermore, as the Social Media Collective states on their blog, cell phones and social networking sites have become an actual necessity in modern-day society. Not being connected is rather an exception to the rule (Karppi, Disconnect.Me 56; Portwood-Stacer 1049). This makes it understandable that people suffer from FOMO (Fear Of Missing Out) whenever they do wish to leave social networking platforms (Wortham).

The urge to be constantly connected is inextricably wired into Western culture (Dijck, Facebook and the Engineering 142). As Van Dijck states, sociality and connectivity in the current society are produced increasingly through networked platforms, such as Facebook (Dijck, Facebook as a Tool 161). She argues that connectivity is imposed on us and that we have no further say in how we are actually being connected. As a result, social networking even turned everyday conversations into commodities, as they can be retrieved and sold for years to come. This is expressed well in the film The Social Network: “[t]he Internet is not written in pencil (…) it’s written in ink (qtd. in Dijck, Facebook as a Tool 166). According to van Dijck “Facebook (…) has stretched the boundaries of the private sphere by pressing its users to divulge intimate details to a general audience” (qtd. in Dijck, You have one identity 200).

The intrusiveness and permanence of social networking sites and connections is mostly perceived as negative, causing more interest in disconnection. Tero Karppi has dedicated his dissertation to the concept of disconnectivity. What happens when users choose to disconnect? Without a connection with users, social networking sites would not exist (Karppi, Disconnect.Me 22). Therefore, platforms like Facebook are designed to make users act rather than think, as thinking about the workings and effects of Facebook might make a user consider disconnecting (Karppi, Disconnect.Me 57). This disconnection affects Facebook, since the platform runs on its engagement with users who provide data, from which the makers of Facebook extract economic value (Karppi, Disconnect.Me 59). The reasons why users choose to disconnect are negative, such as information overload, boredom or even guilt. This increases the disconnection to feel like something positive, creating feelings of accomplishment (Karppi, Disconnect.Me 63).

There have been earlier attempts at disconnecting from social networking sites, of which the Web 2.0 Suicide Machine and Seppukoo.com are the two most recent examples (Karppi, Digital Suicide). The Web 2.0 Suicide Machine worked by applying a script for defriending all Facebook friends and changing the password to prevent future log ins (Needleman). Yet, due to problems with the script, often only a limited amount of friends would get defriended and the Facebook account would remain intact after using their service (Needleman). After running only a short amount of time, the suicide machines were discontinued due to legal actions (Needleman; Karppi, Digital Suicide). They were shut down because of a violation of the Statement of Rights and Responsibilities (Needleman; Karppi, Digital Suicide).

Therefore a new approach to disconnect from Facebook is needed, inspired by the fact that the best resistance comes from within. As Jussi Parikka states: “[…], resistance works immanently to the diagram of power and instead of refusing its strategies, it adopts them as part of its tactics” (118). This notion has led to the creation of our service called Post Mortem, which uses the Terms of Service instated by the makers of Facebook to create a new and improved way for users to disconnect from Facebook. How will Facebook respond when users start using the platform against itself? The service will help users quit Facebook by making Facebook quit them.

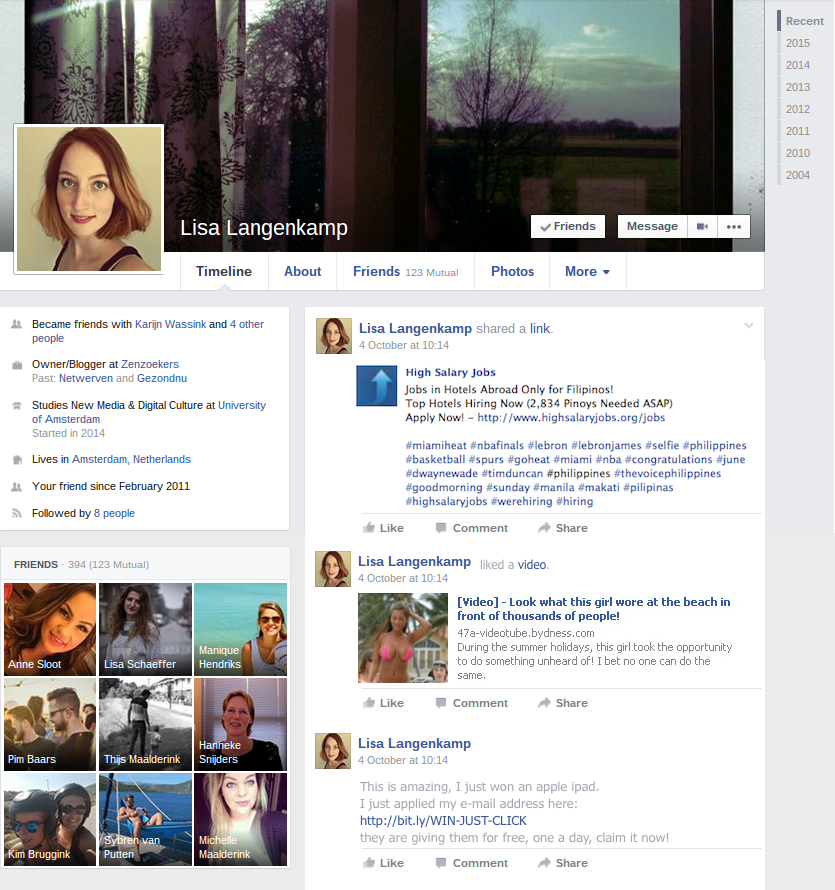

Through in-depth analysis, we categorized the Terms of Service into three different profiles that users can choose from in order to have their profile permanently blocked by Facebook. These three profiles are respectively: ‘with a bang’, ‘the subtle/sneaky route’ or ‘make a change’. Each of the profiles focuses on their own set of Terms of Service. All profiles have the option for users to compose one final post in order for them to say goodbye to all their Facebook ‘friends’. Once blocked, former users cannot reactivate their account or retrieve any of the content they have added or shared, which will make it more difficult to fall back into old habits and get back online (“How Do I Permanently Delete My Account?”). Moreover, instead of simply quitting and thereby disconnecting the service, it is also important to “introduce different potential ways to exist in social networks” (Karppi, Digital Suicide).

Example option 1: with a bang. When choosing this option, your Facebook profile will be spammed with ads and inappropriate (but not illegal) content.

So if you are ready to leave Facebook behind, make your decision final and meaningful. Make Facebook quit you!

Bibliography:

Dijck, José van. “Facebook and the Engineering of Connectivity: A Multi-Layered Approach to Social Media Platforms”. Convergence 19.2 (2012): 141-55.

Dijck, José van. “Facebook as a Tool for Producing Sociality and Connectivity.” Television & New Media 13.2 (2011): 160-76.

Dijck, José van. “‘You Have One Identity’: Performing the Self on Facebook and LinkedIn.” Media, Culture & Society 35.2 (2013): 199-215.

Fishwick, Carmen. “Is Facebook really losing its appeal?” The Guardian. 2014. 16 September 2015. <http://www.theguardian.com/media/2014/jan/23/facebook-losing-appeal-users-social-network-princeton-researchers>.

Gehl, Robert. “Real (Software) Abstractions. On the Rise of Facebook and the Fall of MySpace.” Social Text 30.2 (2012): 99-119.

Hempel, Jessi. “How About a Social Media Sabbatical? WIRED Readers Weigh In.” WIRED. 2015. 13 October 2015.

<http://www.wired.com/2015/08/social-media-sabbatical-wired-readers-weigh/>.

Hempel, Jessi. “Why I Quit My Facebook Quitting.” WIRED. 2015. 13 October 2015.

<http://www.wired.com/2015/09/quit-facebook-quitting/>.

“How Do I Permanently Delete My Account?” Facebook Help Center. 2015. 7 October 2015. <https://www.facebook.com/help/224562897555674>.

““If you don’t like it, don’t use it. It’s that simple.” ORLY?” Social Media Collective Research Blog. 11 Aug. 2011. 7 October 2015

<http://socialmediacollective.org/2011/08/11/if-you-dont-like-it-dont-use-it-its-that-simple-orly/>.

Karppi, Tero. “Digital Suicide and the Biopolitics of Leaving Facebook.” Transformations 20 (2011): n.pag.

Karppi, Tero. Disconnect.Me: User Engagement and Facebook. Diss. (PhD Thesis). University of Turku, 2014. Turku: Turun Yliopiston Julkaisuja, 2014. 6 October 2015. <http://www.doria.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/95616/AnnalesB376Karppi.pdf>.

Kim, Jeannie. “5 things I learned when I quit Facebook.” Health.com. 11 August 2014.

<http://abcnews.go.com/Health/things-learned-quit-facebook/story?id=24907022#all>.

Lang, Nico. “Why teens are leaving Facebook: It’s ‘meaningless’.” The Washington Post. 2015. 16 September 2015.

<https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-intersect/wp/2015/02/21/why-teens-are-leaving-facebook-its-meaningless/>.

Needleman, Rafe. “Facebook cuts off Suicide Machine access”. Cnet. 2010. 16 September 2015. <http://www.cnet.com/news/facebook-cuts-off-suicide-machine-access/>.

Parikka, Jussi. “Ethologies of Software Art: What Can a Digital Body of Code Do?” Deleuze and Contemporary Art. Eds. Simon O’Sullivan and Stephen Zepke. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2010. 116–32.

Portwood-Stacer, Laura. “Media Refusal and Conspicuous Non-Consumption: The Performative and Political Dimensions of Facebook Abstention.” New Media & Society 15.7 (2012): 1041–57.

“Statement of Rights and Responsibilities” Facebook. 2015. 16 September 2015. <https://www.facebook.com/terms.php>.

Wortham, Jenna. “Feel Like a Wallflower? Maybe It’s Your Facebook Wall.” The New York Times. 2011. 16 September 2015. <http://www.nytimes.com/2011/04/10/business/10ping.html?_r=0>.

Zuckerberg, Mark. Facebook. 2015. 16 September 2015. <https://www.facebook.com/zuck/posts/10102329188394581>.