Safety Net – Play With Privacy or It Will Play You

Have you ever used a website that uses cookies? “Liked” a photo on Facebook? Geo-tagged your location in a post or used Google Maps?

Of course you have. But were you aware of how the information you shared about yourself in this process was used, stored or sold online? Moreover, did you know that privacy concerns are a key aspect of academic debates surrounding the media tools you use everyday?

As students of the New Media and Digital Culture MA program at the University of Amsterdam, we found ourselves increasingly aware of the precariousness of our privacy online throughout the course. Even with experience in, and a keen interest of, various aspects of new media, often the information we were learning about Big Data and information collection still came as a surprise. The ignorance we felt towards key issues was echoed and supported by the theory itself; we became increasingly aware of how “[i]ndividuals are often largely unaware that such capta is being generated about their activities and interests[online], except when it is explicitly revealed to them” (Dodge and Kitchin 86).

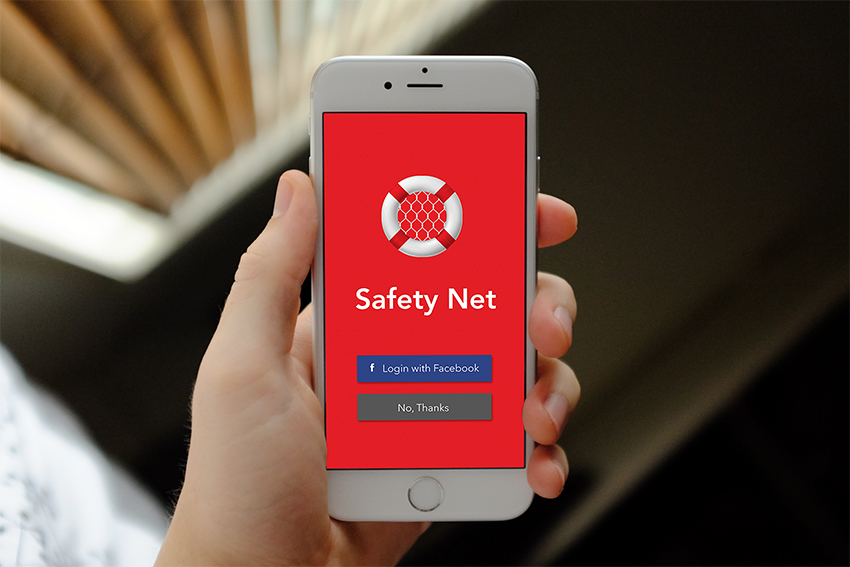

This realization spurred us to come up with a project that would move key academic privacy concerns out of the realm of just academia and literally put them in the palm of the everyday web user. Safety Net is an educational mobile application that is designed to be interactive, fun and informative. The app is primarily a series of informative games, each based around a specific web feature– for example, the GPS Location feature, cookies and the Facebook “Like” button. By anchoring information about data collection and privacy to common features of the internet, Safety Net gently leads users from concrete examples of privacy concerns to larger theoretical perspectives that can be applied across their web practices more generally. Safety Net seeks to intervene on two levels: by making academic privacy concerns understandable to everyone, and by providing web users with the practical information necessary to be more critical and aware of the information they willingly or unwillingly share on the web.

Media theorist dana boyd states that “[p]rivacy is not about control over data nor is it a property of data. It’s about a collective understanding of a social situation’s boundaries and knowing how to operate within them. In other words, it’s about having control over a situation” (boyd, “Privacy and Publicity in the Context of Big Data”). With this perspective as the backbone of our application, Safety Net seeks to give users both a greater understanding of and control over the data they create online.

Ideally, the user leaves each game with a honed critical ability to ask for themselves the questions raised by Lisa Gitelman in the introduction to “Raw Data is An Oxymoron”:

“What are the logics and the ethics of “dataveillance,” now that we appear to be moving so rapidly from an era of expanding data resources into an era in which we have become the resource for data collection that vampirically feeds off of our identities, our “likes,” and our everyday habits?” (Gitelman 10).

So, How Exactly Does It Work?

The app has several different games on specific web features such as GPS and location tagging, cookies, etc. All of these games have different interfaces to keep the user’s interest alive, but have common elements that combine theory with functional tips.

For example, we created a game that centers around the privacy concerns raised by cookies in ad-tracking. Our main concerns were that cookies help target advertisements to users based off of their browser history but that these “preferences are not consciously or explicitly set by the user” and “there is no obvious notice or notification sent to the user that the user’s actions online are being tracked for ad-serving purposes” (AllAboutCookies.Org). Using the technology of websites such as https://disconnect.me/, an open-source platform that “lets you visualize and block the invisible sites that track your search and browsing history,” our application asks users to enter a specific website into a search bar and shows them the corresponding number of third-party trackers present on that website. This determines the number of ‘enemies’ the user must face in the application game, creating a direct correlation between the interactions on their screen and the real life insecurity of their data on their preferred website. By incorporating these technologies, Safety Net seeks to provide technical resources to the app’s users to further investigate their own privacy online while delivering these tools in an approachable and non-pedagogical manner.

Additionally, each game has a pause screen, where users can seek more information mid-game. For instance, in our GPS game, the user must dodge applications that track your location and ‘collect’ the ones that do not. The user may pause the game at any point to demand additional information about the particular applications on their screen. Throughout, cartoon iterations of the theorists we’ve connected to these concerns (dana boyd, Michel Foucault, Robert Kitchin) pop up with idioms and quotations from theoretical texts that help the user draw preliminary connections between the actions they are taking on screen and the underlying privacy concerns associated with each specific web feature.

Safety Net draws on what Lev Manovich calls “the new rhetoric of interactivity” – rather than simply providing users with “a prepared message,” we ask them to partake and engage in their own data creation – “reorganizing it, uncovering the connections, becoming aware of correlations” (Chun 51). The games ask the user to become an active and conscious creator of information online. By providing further resources and practical tips, the game directs users to additional information that they can interpret and apply across their web use on other platforms with greater knowledge and agency.

Reflection

While our project is still in mock-up form, the process of researching for this idea spurred our group’s engagement with multiple media platforms and applications and caused us to challenge our own media habits. Both the practical research and the visual implementation of this mock-up pushed our group to use a variety of media: from researching existing gaming applications to choose fun, easy-to-use designs for our games to realize through Illustrator and Sketch, to the use and emulation of privacy tools such as Disconnect.Me. Particularly, the constant use of Google Docs, Scholar, and Search to research and share information became increasingly uncomfortable for us as we learned more about our own data footprints online. Throughout this project, we ended changing our own browsing habits, implementing the same additional security measures we recommend to Safety Net users on the ‘Practical Tips’ screens. We downloaded ‘Share Me Not,’ a web-extension that prevents third-parties from tracking your online browsing, and became increasingly critical of how Facebook continued to target ads to us that matched our recent search histories – for example, by recommending websites similar to the ‘FaceYourManga’ site we used to ‘cartoonify’ our theorists. The degree of self-reflectivity spurred by this element of the project cemented our desire to bridge the gap between theory and practice. Through this experience, we became confident that if truly developed, Safety Net would bring about real changes to users’ web habits and help arm them with the discerning viewpoint through which to challenge and understand their own privacy online.

The Safety Net Team

Deniz Gülsöken, Brittany McGillivray, Clemens Buchegger, Daniela Demarchi, Leo Goryachev

Works Cited and Consulted

Agre, Philip. ‘Surveillance and Capture: Two Models of Privacy. The New Media Reader. Eds. Noah Wardrip-Fruin and Nick Monfort. Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 2003. 737-760.

boyd, danah. “Privacy and Publicity in the Context of Big Data.” danah boyd’s writing. WWW. Raleigh. North Carolina, April 29. October 2015. <http://www.danah.org/papers/talks/2010/WWW2010.html>

boyd, danah. “What Is Privacy?” danah boyd | apophenia. danah boyd. September 2014. October 2015. <http://www.zephoria.org/thoughts/archives/2014/09/01/what-is-privacy.html>

Chun, Wendy. On Software, or the Persistence of Visual Knowledge. Grey Room 18. (2004): 26-51.

Dodge, Martin, and Rob, Kitchin. Code/Space: Software and Everyday Life. Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 2011.

Foucault, Michel. “The Subject and Power.” Chicago Journals. 8.4 (1982): 777-795.

Gitelman, L. (ed.) 2013. Raw Data Is an Oxymoron. Cambridge: MIT Press. Introduction chapter.1-14.

Websites Used:

Digital Methods Initiative. 2015. Digital Methods Initiative. 16 October 2015. <www.digitalmethods.com>.

“Privacy Debates and Tools”. Masters of Media Wiki. 21 Sept 2014. 25 September 2015. <https://www.digitalmethods.net/MoM/PrivacyDebatesTools#A_4._References>

“Privacy Policy”. 2015. Foursquare Labs, Inc.. 16 October 2015. <https://foursquare.com/legal/privacy>

“Privacy Policy”. 2015. Telegram. 16 October 2015. <https://telegram.org/privacy>.

“Privacy Concerns on Cookies”. 2015. AllAboutCookies.org. 16 October 2015. <http://www.allaboutcookies.org/privacy-concerns>.

“Understanding Online Advertising: FAQ”. 2015. Network Advertising Initiative. 16 October 2015. <http://www.networkadvertising.org/faq>.