Browsing from the right side of history: political polarization online

To many, the old ghosts of the far-right appear to have come back from the dead. Trump, Wilders, Le Pen, Petry, Orbán, Hofer, Fujimori in Peru and Bolsonaro in Brazil — all of these figures announce the unexpected return of radical historical forces long deemed to be dying and won over. And yet, to them, the world is entering a new dawn of age. Farage has just recently proclaimed a “national day of independence” in the UK, and America is about to be great again.

How can living in the same planet become such a polarizing experience?

PhD theses on the matter are just being published, as NPR, the BBC, The New York Times and even political figures, to cite Obama, have expressed worry at “the nature and the extent of [political] polarization” today. (Hofbauer) In the US, “[t]he partisan divide among Democrats and Republicans has intensified to its highest level in nearly 25 years”. (Mitchell et al.)

The “nature” of this polarization has its own history. (Yardi and boyd) Mediums such as newspapers are known to be partisan; Breitbart News embraces its biases and critiques “mainstream media” for not showing its true colors, for instance. Headlines, choice of facts, scoops and headlines — language — is something we, as citizens, have learned to decode quite well in school, anyway.

But by 2011, studies have begun to question the new dimensions of political life in new media particularly. They sought to understand how technicalities would bring new meaning and affordances to the political engagement of users, worrying that, with the emergence of the web 2.0, user-centered algorithms made newsfeeds and search results be echo-chambers. (Pariser; Gentzkow and Shapiro; Messing and Westwood; Yardi and boyd)

With the success of Google’s PageRank and Facebook’s Newsfeed, newspapers and other traditional sources of information followed suit and opened personalized windows throughout their websites. These same news websites opted to release information via major social media platforms, with Facebook being the vector of over 25 billion web articles per month, as per 2010. (Messing and Westwood)

Today, with about 44% of Americans consuming information from their social media accounts and Facebook now having a population of 1.7 billion users worldwide, new media has become one’s main environment from which to not only fetch information, but to observe, nurture, stimulate, and discuss it, too. (Yardi and boyd) Now, then, the challenge resides in decoding the entire re-designing of our environment and perception online, and of which the infrastructures are not always visible, whether we are politically engaged or not.

Other studies, including one released by Facebook itself, claim that the online homogeneity is only a reflection of choices people make offline. We may well be more in touch with “weak ties”, who are most likely to confront us with divergent opinions. (Barberá) And if only users chose their friendships more at random, progressives would be exposed to 45% more divergent information and conservatives to 40%. (Bakshy, Messing, and Adamic)

Clearly, various other social, cultural and economical factors remain powerful forces to guide one’s political preferences. But their own codes and algorithms may be in considerable competition with those that Google and Facebook write. (Alwin and Tufiş)

Even though people do have a choice to decide on the content they will see, they will have to resist the friends, events, pages, groups, and posts that Facebook presents them in the first place. Choices are plenty, but the act of making these has its artificial constrains: users will opt between recommended clicks. (Pariser)

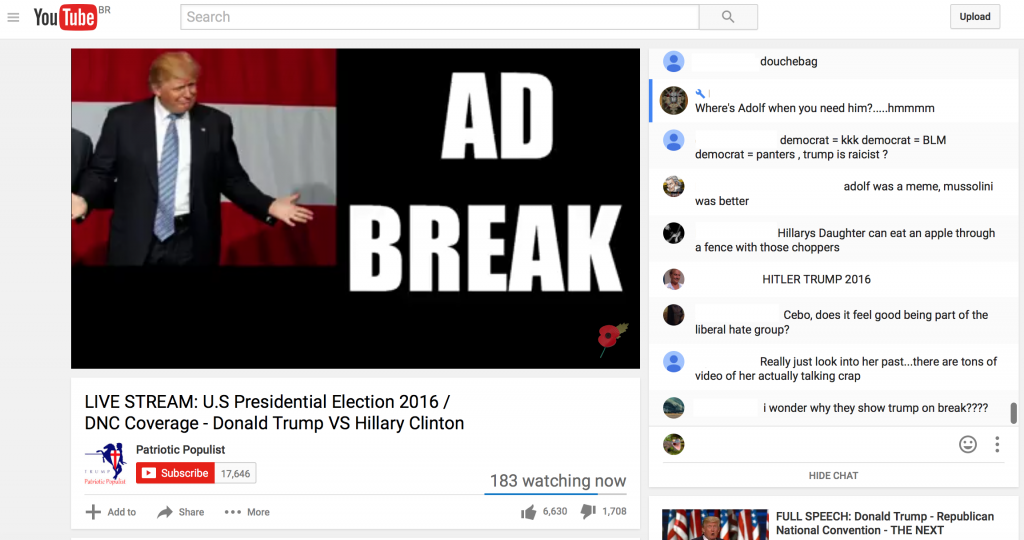

And, so, the fact that information be propagated in a “a priori” polarized environment must reduce the possibility for opposing parties to be understood, let alone seen or heard — or not to be opponents in the first place. With distinct batches of information, users form distinct opinions with distinct facts. On Twitter, “there is usually little conversation between these groups despite the fact that they are focused on the same topic. [They] are not arguing. They are ignoring one another while pointing to different web resources and using different hashtags.” (Smith et al.)

Without much common ground to discuss in, users are poorly incited to discover their opponent’s point of view. “People [encountering] roughly 15% less cross-cutting content in news feeds due to algorithmic ranking and click through to 70% less of this cross-cutting content.” (Bakshy, Messing, and Adamic) So conflicts start: differing points of view become so foreign that we resist engaging with them. (Prior) “Of all the links seen by people who consider themselves to be progressive, only 22% challenge their way of thinking.” (Bakshy, Messing, and Adamic)

“Where is Adolf when you need him?”

The real challenge, it seems, is to find ways to step out of homogeneity.

Some suggest the solution has to be socio-technical. Cross-linking between ideologically competing groups, promoting competing views in like-minded groups, and voting and ranking algorithms are all viable options. (Yardi and boyd) “Old media” has already tackled this problem; a law in Brazil obliges companies to include Afro-descended and indigenous Brazilians on their advertisements.

But when it comes to political life, Facebook and Google need to step up to their responsibilities and invest their creativity in digital diplomacy. If Facebook is not a “media” but a “tech” company, perhaps it should stop behaving like one.

Some other times, to stop relying on popular platforms and re-appreciate our universe’s own algorithms can also help. It requires seeing information that is not pre-packaged; to experience the world as something to still make sense of.

If not, we will agree on at least one thing: that our opponents are unbearably closed-minded.

Works Cited

Alwin, Duane F., and Paula A. Tufiş. “How the Culture Wars Are Driving Political Polarization.” Website. USApp – American Politics and Policy Blog. N.p., 1 Apr. 2016. Web. 12 Sept. 2016.

Bakshy, Eytan, Solomon Messing, and Lada A. Adamic. “Exposure to Ideologically Diverse News and Opinion on Facebook.” Science 348.6239 (2015): 1130–1132. science.sciencemag.org. Web.

Barberá, Pablo. “How Social Media Reduces Mass Political Polarization. Evidence from Germany, Spain, and the US.” Job Market Paper, New York University (2014): 46. Google Scholar. Web. 18 Sept. 2016.

Gentzkow, Matthew, and Jesse M. Shapiro. Ideological Segregation Online and Offline. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2010. National Bureau of Economic Research. Web. 14 Sept. 2016.

Hofbauer, Tara. “A Study of the Effect of Online News Consumption on Political Polarization and Deliberative Democracy.” Diss. U of Pennsylvania, 2015. Abstract. N.p., 138. Web.

Messing, Solomon, and Sean J. Westwood. “Selective Exposure in the Age of Social Media: Endorsements Trump Partisan Source Affiliation When Selecting News Online.” Communication Research (2012): 23. Print.

Mitchell, Amy et al. “Political Polarization & Media Habits.” Pew Research Center’s Journalism Project. 1. 21 Oct. 2014. Web. 12 Sept. 2016.

Pariser, Eli. The Filter Bubble: How the New Personalized Web Is Changing What We Read and How We Think. Reprint edition. New York, NY: Penguin Books, 2012. Print.

Prior, Markus. “Media and Political Polarization.” Annual Review of Political Science 16.1 (2013): 101–127. CrossRef. Web.

Smith, Marc A. et al. “Mapping Twitter Topic Networks: From Polarized Crowds to Community Clusters.” Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. 1. 20 Feb. 2014. Web. 18 Sept. 2016.

Yardi, Sarita, and danah boyd. “Dynamic Debates: An Analysis of Group Polarization Over Time on Twitter.” Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society 30.5 (2010): 316–327. bst.sagepub.com. Web.