Decapitation? Here’s a wise old lady who knows better

Changing the minds of IS-fighters-to-be while they are searching for IS-related material on YouTube sounds like a contradiction, but Google found a subtle way to do so.

This month, Google’s think-tank Jigsaw is launching an unconventional project called the Redirect Method which tries to dissuade potential Islamic State (IS) recruits, using one of Google’s best skills: (targeted) advertising.

The Redirect Method: showing a counter-narrative

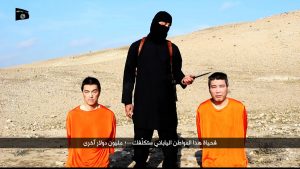

Screenshot 1: IS executioner ‘Jihadi John’, one of the central figures in IS’ execution videos

Google’s Jigsaw uses technology to counter geopolitical issues, such as digital attacks, injustice and corruption, attacks on free speech or, in this case, violent extremism. IS’ online propaganda campaign uses video-sharing platform YouTube to disseminate its ideology and military victory worldwide and plays an important role in IS’ online recruitment strategy (Veilleux-Lepage, para. 3). The YouTube content, with slick production values and graphics, is used to show potential recruits a stable and growing Islamic empire, but also glorifies violence and martyrdom. “IS relies on the dissemination of its narrative to foster support both domestically and abroad through a uniquely effective social media strategy (ibid.).”

The Redirect Method focuses on people ‘who are actively looking for extremist content’ and tries to identify people susceptible to IS recruitment videos on YouTube, based on patterns in their online behavior and IS-related keywords they searched for (The Redirect Method). Instead, The Redirect Method showed those people a counter-narrative to this IS propaganda through videos and ads linking to already existing YouTube material, using targeted advertisements and search suggestions.“Those ads link to Arabic- and English-language YouTube channels that pull together preexisting videos Jigsaw believes can effectively undo ISIS’s brainwashing” (Greenberg, Wired.com) and dissuade young, vulnerable people from joining or sympathizing with IS. The content includes, for example, a speech by an imam speaking out against IS, a video showing IS rule in Raqqa or an elderly woman standing up against IS.

Libertarian paternalism: influencing behavior

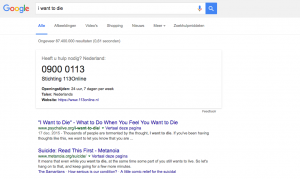

Screenshot 2: Google showing the number of the suicide prevention hotline

Jigsaw’s Redirect Method is certainly not the first time a company like Google is trying to steer users towards or away from specific behaviors, this strategy is known as ‘nudging’ (Thaler & Sunstein 6). For example, Google added a feature to its search engine in 2010 that shows people who are searching for suicide-related topics the number of a suicide prevention hotline in order to prevent people from committing suicide.

Google is able to do this through “the organization of search results by a sophisticated and proprietary algorithm that allows Google to direct users towards a set of choices (Troumbley 24).” Guiding people in a direction that will improve their decisions without eliminating their freedom of choice, is what Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein call ‘libertarian paternalism’ (4). Using the Redirect Method, Google’s Jigsaw is able to make a libertarian paternalistic intervention on YouTube by guiding potential IS-recruits to different materials, which hopefully improves their decision. In paternalism “lies the claim that it is legitimate for choice architects to try to influence people’s behavior in order to make their lives longer, healthier, and better” (Thaler & Sunstein 5). Libertarian paternalism is a more soft and nonintrusive type of paternalism because choices are not blocked, it strives to maintain freedom of choice (ibid). If people want to watch IS-promoting content on YouTube, Jigsaw’s libertarian paternalistic intervention will not block material that advocates IS’ ideology. Jigsaw’s method can be seen as socially driven libertarian paternalism as described by Gill & Gill, a type of paternalism which also serves society, in this case by reducing radicalization (928).

“Limited information, time, and cognitive ability mean that people do not evaluate options perfectly (Gill & Gill 925).” By offering an alternative to the one-sided message in IS propaganda videos on YouTube, Jigsaw is trying to direct potential IS-recruits towards a better and more rational decision. Although the Redirect Method seems like a subtle and sympathetic way of Google to combat IS, it also raises the question what the boundaries are in redirecting people and trying to change their behavior. Users “tend to trust proprietary engines as neutral mediators of knowledge (van Dijck 574).” Search results have a significant impact on a user’s choice, mainly because users trust and choose higher-ranked results more than lower-ranked results (Epstein & Robertson 1), search engines are thus able to manipulate choices without a user’s conscious knowledge.

Jigsaw’s Redirect Method imposes Google’s own value system of what’s right and what’s wrong on the search results and advertisements. In this case for a good cause: making the world a safer place by reducing radicalization. But clearly the Redirect Method opens possibilities to less sympathetic nudging on YouTube and other social media. Is it legitimate for a company like Google to decide what is good behavior? This might be a step towards a ‘filter bubble’ in which users only get to see what Google wants them to see.

Conclusion

Extremist groups like IS use social media like YouTube to spread their propaganda and recruit new fighters. Jigsaw’s Redirect Method uses a libertarian paternalist approach by deploying targeted advertising and search results in order to dissuade vulnerable people from joining IS. This approach is both libertarian and paternalistic because it retains freedom of choice while it’s also leading people to better choices. However, this method is on a slippery slope because it imposes Google’s vision on what’s right and wrong behavior.

Bibliography

Dijck, José van. “Search engines and the production of academic knowledge. International Journal of Cultural Studies 13.6 (2010): 574-592.

Epstein, Robert, and Ronald E. Robertson. “The Search Engine Manipulation Effect (SEME) and Its Possible Impact on the Outcomes of Elections.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112, no. 33 (August 4, 2015): 4512–21

Gill, Nick, and Matthew Gill. “The Limits to Libertarian Paternalism: Two New Critiques and Seven Best-Practice Imperatives.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 30, no. 5 (October 1, 2012): 924–940

Greenberg, Andy. “Google’s clever plan to stop aspring IS Recruits.” Wired.com. 9 July 2016. https://www.wired.com/2016/09/googles-clever-plan-stop-aspiring-isis-recruits/. Accessed on 17 September 2016

Thaler, Richard H., and Cass R. Sunstein. Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. Yale University Press, 2008

Troumbley, Rex. “Coercive Cyberspaces and Governing Internet Futures.” The Future Internet: Alternative visions, edited by Jenifer Winter, Ryota Ono, 2015, pp. 17-40.

Veilleux-Lepage, Yannick. “Retweeting the Caliphate: The Role of Soft-Sympathizers in the Islamic State’s Social Media Strategy.” Conference paper, presented at the 6th International Symposium on Terrorism and Transnational Crime, Antalya, Turkey. 2014.