The promise of total Tinderization

The Art project “Tender” was built by students at Leiden University

Tinderization of Feeling

Yup, like a lot of my contemporaries, I’m spending alarmingly big heaps of time on dating apps. Leaving aside all that bodyshaming, occasional racism and the paralysing insecurities that they promote, they can be a lot of fun – especially Tinder, the app that offers you loads of faces that you can either approve or reject (swipe). And since the application only sets you up (matches) with people that feel the same affirmation towards you as you feel towards them, your reward centre is instantly addressed. (Collecting matches; it’s basically a sexually charged version of Pokemon.)

At this point already, the matching-mechanism sparks some concern: Tinder’s selection-process is making room for a new implementation of Dating-Darwinism. By reducing the partner search to mainly visual components* it’s obliterating a huge variety of complex and dynamic factors such as body language or biochemistry. These components still play a part in approaching people, but are subordinated in regards to people’s visual appearance.

Furthermore, this reconfiguration of sexual codes leads directly to a rise of objectification among users, as many of them are “more likely to think of themselves as sexual objects, to internalize societal ideals about beauty, to compare their appearances to others and to constantly monitor how they looked.” (Oaklander) – People become Profiles. This issue is directly linked to Mel Stanfill’s argument that Interfaces, through the use of affordances and their particular way of constraining user’s actions, organise social structures (Stanfill 2015). Because Tinder’s interface focuses mostly on the suggested users visual appearance, you instantly shift more importance towards your own appearance.

Considering all these implications, Alicia Eler and Eve Peyser, in their essay for The New Inquiry, endorse the concept of Tinderization as a social, political and economic template that forces humans to act more and more robotic: “Within Tinder, we sort each other into ones and zeroes, flattening away any human complexity, becoming efficient robots.” (Eler and Peyser)

Tinderization of Politics

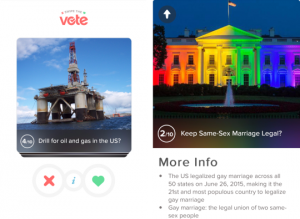

While this lack of decisiveness induces it’s own kind of problems regarding relationships and dating, it becomes even more controversial on a political level. Interestingly, Tinder released a new feature this April in the context of the 2016 Presidential elections in the U.S. ‘Swipe the Vote’ was introduced in order to help users decide on who to vote for:

“Starting today, users in the U.S. may see a ‘Swipe the Vote’ video card when they are swiping. Simply tap on the card and to swipe right on stances you agree with and left on those you don’t.”

-(Statement on Tinder’s Official Homepage)

Screenshots of “Swipe the Vote”

Once users have swiped through ten politically brisant questions (same-sex marriage, health insurance,..) they’re presented the result and are matched with a candidate (e.g. 90% Donald Trump). As the process of deciding becomes increasingly simpler, users assign more and more power to the algorithm, especially if these decisions are mainly approached through binary means. ‘Swipe the Vote’ implicates the Tinderization of political thought; it almost makes you want to say “Swipe the Vote away”.

That binary yes/no logic, as already hinted on by Alicia Eler and Eve Peyser, leaves one aspect of the human condition aside: the state of being indecisive. And although the prospect of “not exactly knowing” may seems romanticised and outdated, let’s consider the subversive potential of “maybe”. Because of the fact that the app forces you to make a decision instantly in order for you to get new potential matches, it doesn’t allow you to step back for a moment in order to contemplate and consider things. However, when facing a struggle, we are forced to think and confront ourselves: The process of questioning circumstances is the basis for reflection.

When thinking about Tinderization, the irony behind automation’s former cry for simplification becomes discernible: while all aspects of our lives are getting more and more intertwined with technology in order to simplify our decision-making, Tinderization points out the prospect of us becoming more automated and robotic. That’s why we should consider “maybe” as a productive space. A posture that allows us to the exit the logics of Tinderization and (maybe) just struggle for a bit.

———

- Apart from references to the person’s educational and professional background and quirky, generic self-descriptions.

References

Eler, Aler and Peyser, Eve: “Tinderization of Feeling”

http://thenewinquiry.com/essays/tinderization-of-feeling/

Martis, Eternity: “Canada’s Tinder Men Are Annoying Black Women with Their Racist and Sexist Bullshit”

Mayyasi, “Alexa: Online Dating and the Death of the ‘Mixed-Attractiveness’ Couple”

https://priceonomics.com/online-dating-and-the-death-of-the-mixed/

Oaklander, Mandy: “Tinder Users Have Lower Self-Esteem: Study”

http://time.com/4439084/tinder-online-dating-self-esteem/

Stanfill, Mel. 2015. The Interface as Discourse: the Production of Norms Through Web Design. New Media & Society 17 (7): 1059–1074.

Tinder’s official Homepage: