Saintify.me (A Critical Intervention)

by Catherine Mills, Matthias Nothnagel & Georgina Ustik

Introducing Saintify.me, a browser extension that makes activism simple and easy!

Image 1: Logo for Saintify.me extension

Concept

“Being good has never been so simple.”

– Catherine Mills, Georgina Ustik, Matthias Nothnagel

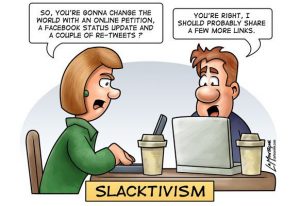

Social media sites have introduced the opportunity for wide-scale, online social and political participation. The variety of civic engagement and activism in the realm of new media – also referred to as Slacktivism or Armchair Activism – is huge and online participation can range from petitions, to posts, tweets, and even hacker activism.

But in what ways do new media technologies reinforce the social and political change they actually promote? To what degree is online activism intertwined with the user’s self-presentation? And does Slacktivism help or hurt activist efforts?

Image 2: Cartoon on Slacktivism

Generally, two perceptions of online activism exist in opposition to each other:

On one hand, scholars point out the lack of effectiveness of Online Activism. Evgeny Morozov criticizes what he calls “technological solutionism,” a term describing the current rise of technologies that claim to simplify user’s lives, but, according to him, actually neglect the real problem that they pose to have a solution for (Morozov, 2013): The technology itself is becoming more important than the problem it claims to solve. Within the context of Slacktivism, Morozov furthermore elaborates on some online campaign`s “unrealistic assumption that, given enough awareness, all problems are solvable” (Morozov, 2009). When speaking about Slacktivism, Yu Hao Lee and Gary Hsieh argue that it is only substituting “other civic actions because the people’s inner urge to take action has been satisfied by their participation in the low-cost online action.” (Lee, Hsieh) If Slacktivism comes at the cost of activism, and not an additional component, it could hinder social, political and economic progress by removing actors from the higher-risk frontlines, and move them behind a computer screen.

Image 3: Cartoon on Slacktivism

On the other hand, some campaigns have proven that online activism can actually enable political and social change, as seen in 2014 with the global reach of the “Ice Bucket Challenge”: The social media campaign raised over $100m within one month, and was able to fund a number of research projects, resulting in the discovery of a common gene contributing to Lou Gehrig’s disease (Woolf).

Image 4: Person taking part in Ice Bucket Challenge for ALS

In order to intervene in these debates, we decided to inscribe ourselves into the logic of Slacktivism and accelerate its structures and mechanisms to the point where they are revealed. How would that be possible?

Our Solution: A browser extension for Facebook that automatically manages the user’s social awareness public profile to allow for easy managing of social media “empathy” and participation in top trending international social causes. Saintify.me, as the name already suggests, engages with and mocks the argument that every case of online civic participation is directly aimed at improving a user’s social media appearance. By proposing a fully automated mechanism that takes over all actions concerning online activism, it supports the notion that users actually don’t have to participate in any political and social issues anymore. Saintify.me is promoting a generation-wide, unified idea of “feel-good online activism [with] zero political or social impact” (Morozov, 2009).

How Saintify.me works

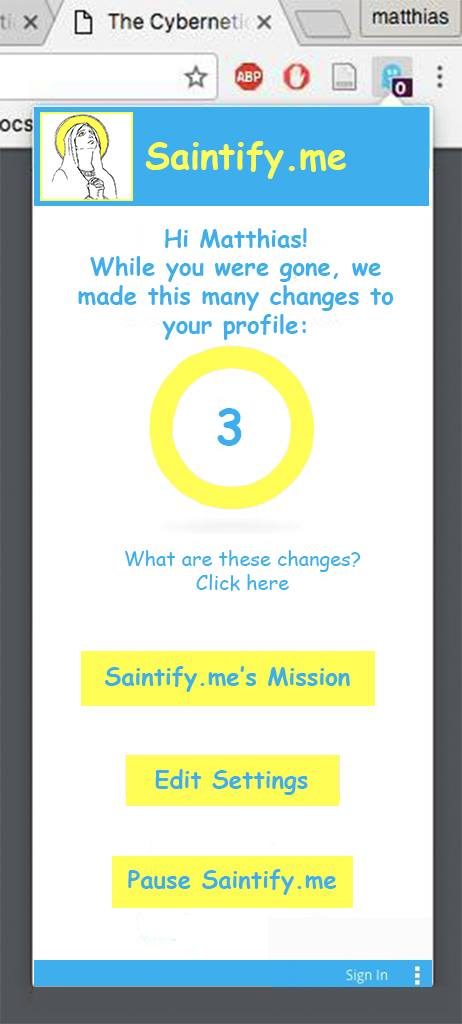

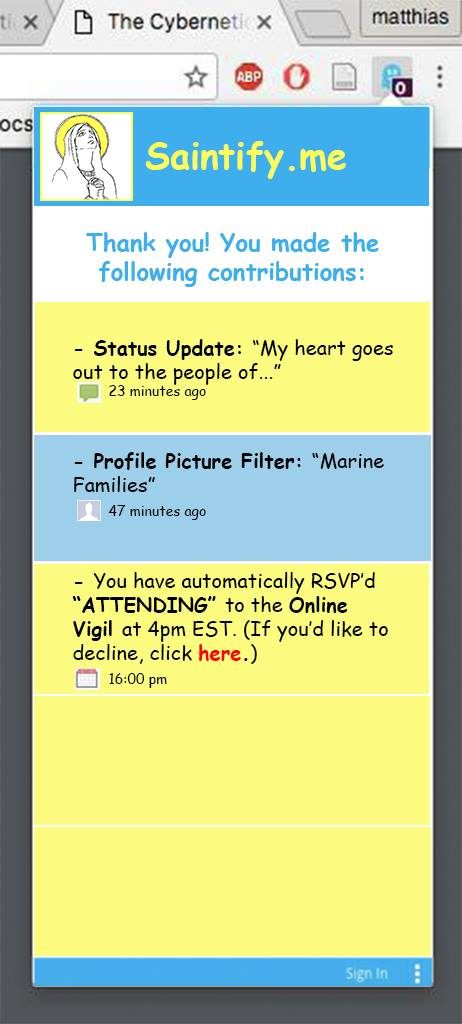

In lieu of actually creating the extension we decided to create a mockup of the extension to show how it would function. It was decided that to highlight the issue of Slacktivism the extension would be as simple to use as possible. As you can see from the mockups, there are very few options on the interface of the extension, so the user has little intervention or choice. Therefore, the extension pivoted around the idea that the user would be able to install the extension with one-click and after this; unless they chose to paused it, it will always appear in the browser. Saintify.me would then automatically update certain features of the user’s Facebook profile, including automatic status updates, profile photo filters and the creation of Online Vigils.

Fig. 1: Mock-up of Saintify.me extension

Fig. 2: Mock-up of Saintify.me extension

For the status updates, the extension would automatically post statuses crafted by a central “Editor” to users’ profiles. The statuses would be a sympathetic but generic message, and could sound something like: “My heart goes out to the family and friends of those affected by the (event) in (city or country).” The statuses would also include both real trending and fictional satirical hashtags (such as #iCare or #TheyNeedThisStatus). The profile photo filter would be akin to the ones already used by Facebook, like the ones made available recently for LGBTQ rights (#celebratepride) and the terrorist attacks in Paris. The filter is applied to all users’ profile picture when signalled by the Saintify.me app. The third element is the creation and access to Online Vigils, which would consist of a Facebook Group page where people can post their condolences about the event that has taken place. It functions largely as a chat room, further provoking the idea that the news events turn into social events. All of these features will have a time limit to reflect the constantly shifting attention of social media. Saintify.me will automatically revoke its features from the user’s profiles as soon as the trending data diminishes to 30% of its peak performance.

We felt it was important to eliminate the need for user’s to keep up with current affairs or discover new information for themselves, so Saintify.me utilizes the Facebook Trending news feed algorithms. Because Facebook Trending is currently only available in the United States, the extension will initially be made available only in the U.S. Facebook’s algorithm works to pick up news stories about the tragedies that are currently being most shared and read by Facebook users. Then an “Editor” from Saintify.me subjectively selects the tragedies they deem most suited to our users and creates the relevant content. It will then be pushed out to everyone. We purposely made the interface very simple, almost like a child’s website, to further eliminate intervention by the user.

Curating the entire output of Saintify.me, and by extension the user’s Facebook profiles, is a central “Editor.” The Editor’s role will be to subjectively decide from the results given by Facebook Trending which tragedy is most “relevant” to the user’s and then generate a relevant filter, status about the tragedy and create an Online Vigil, to which the user’s of Saintify.me will be automatically RSVP’d. These three features would then be pushed out to all users, so that the uniformity for every user’s profile would emphasize the lack of action being taken by the users.

The Interface of Saintify.me

While the overall appearance of the interface of Saintify.me plays an important role in the utility of the extension (few choices = less intervention by the user), we were also careful in making sure the aesthetic was in line with our concept. We chose Comic Sans as the typeface for the extension, as studies have found that the words most commonly associated with it are “childish, shallow, immature and infantile” (Garfield). Therefore, it symbolically fits with how simplistic the app is, while giving it the appearance of a child’s website.

When making our decision for a logo for Saintify.me we took an image of the Virgin Mary from an art historical image search. We then simplified the image, making it appear crude and simple. This process had a twofold result. The app logo, with it’s bold lines and few colors, took on the appearance of many familiar app logos, such as the Snapchat ghost. The logo also conveys how the extension takes what was originally intended to be an altruistic, thoughtful act but is then turned into something shallow. The color scheme for the graphics of the extension are blue, white and gold because of the connotations in art history with them being ‘holy, divine colors.’ It is through these graphic choices that we also convey Saintify.me’s tongue-in-cheek message, where users should believe they are holier than thou by becoming involved in Slacktivism.

While we did not actualize the project and build the extension, Saintify.me is a very doable project, especially as it builds upon features already part of Facebook. If successful, it would also be interesting to take it to other platforms with trending features, such as Twitter and Instagram.

Live from the Left Wing

Apart from the mock-up visualizations of Saintify.me, a satirical, fictitious podcast called “Live from the Left Wing” will be used as a tool to engage with the oppositional discourses on Armchair Activism. We wrote the script for the episodes, and then recorded the dialogue using the GarageBand application, utilizing stock music clips to make the episode seem more like an actual talk show.

“Live from the Left Wing” will include two episodes of three to five minutes each. Each episode will have an interview or exchange between the host, German cultural critic Marshall MacGoogle (MacLuhan+Google=MacGoogle), and an advocate for the extension, characters that we, ourselves, play. The first will be between the co-founders and MacGoogle and will begin the critique of Slacktivism as well as set the context for how the idea came to be. The second will be between MacGoogle and the Editor of Saintify.me, and will explain the features of the extension and further critique Slacktivism and social media as a news source.

“Live from the Left Wing” also works to critique Facebook’s Trending section. As Facebook states, “Trending shows you a list of topics and hashtags that have recently spiked in popularity on Facebook. This list is personalized based on a number of factors, including Pages you’ve liked, your location and what’s trending across Facebook.” (Facebook) The company’s explanation on how the Trending section works is as follows: “Trending shows you topics that have recently become popular on Facebook. Trending topics are based on factors including engagement, timelines, Pages you’ve liked and your location. Our team is responsible for reviewing trending topics to ensure that they reflect real world events. On a computer, the topics are grouped into 5 categories: All News, Politics, Science and Technology, Sports and Entertainment.” (Facebook) Users are served “trending” news that is deemed relevant to them based on personal factors. According to a recent study, 62% of U.S. adults use social media as a news source, and 66% of Facebook users (Gottfried, Shearer), despite Facebook’s claims that “we’re not a media company. When you think about a media company, you know, people are producing content, people are editing content, and that’s not us.” (D’Onfro) In fact, Facebook has been accused of editing their trending section to suppress conservative news stories and add artificially add stories that were not trending. (Nunez) Saintify.me’s inclusion of an Editor who subjectively selects the stories deemed “relevant” to push out to the users is in response to this.

This podcast series is meant to utilize audio media to provide more information and context for the extension, discuss some critical theories against Slacktivism and social media as a news source, as well as set-up the fictitious world in which this extension actually exists. While the extension Saintify.me is a conceptual project and is not actualized, the podcast is an executed part of the project. We have included links to the podcasts which we released on SoundCloud here:

Conclusion

Saintify.me is a satirical critical intervention into Slacktivism, but it is important to look at all aspects of the discussion. Defined as a “low-risk, low-cost activity via social media whose purpose is to raise awareness, produce change, or grant satisfaction to the person engaged in the activity,” (Rotman et al.) Slacktivism carries with it a negative connotation, with a heavy-handed reference to the self-satisfying aspect of it. However, it can, as found with the A.L.S. Ice Bucket and the study conducted by Lee and Hsieh, increase awareness resulting in donations.

Because of social media, the ability to partake in activism is more democratized than ever – anyone with internet access can be a part of a cause, and awareness spreads quickly. However, the passivity of Slacktivism is potentially the most harmful aspect to activist efforts, and it is important to be critical of whether or not you are actively living up to the political persona and beliefs you have created online in the physical world. “Living your politics” is where Slacktivism and activism meet. And if that’s not for you, Saintify.me’s extension will be available in the Chrome Web Store soon. With our extension, being good has never been so simple!

References

D’Onfro, Jillian. “Facebook Is Telling the World It’s Not a Media Company, but It Might Be Too

Late.” Business Insider. 29 Aug. 2016. Web.

Garfield, Simon. “What’s so Wrong with Comic Sans?” BBC News. 20 Oct. 2010.

Gottfried, Jeffrey, and Elisa Shearer. “News Use Across Social Media Platforms 2016.” Pew

Research Center: Journalism and Media. 26 May 2016. Web.

“How Does Facebook Determine What Topics Are Trending? Facebook Help Center.” Facebook.

N.p., n.d. Web. 21 Oct. 2016.

Lee, Y. H., & Hsieh, G. (2013). Does slacktivism hurt activism?: The effects of moral

balancing and consistency in online activism. In Conference on Human Factors in

Computing Systems – Proceedings. (pp. 811-820).

Morozov, Evgeny. “From Slacktivism to Activism.” Foreign Policy. 5 Sept. 2009. Web.

Morozov, Evgeny. “The Brave New World of Slacktivism.” Foreign Policy. 19 May 2009.

Web.

Morozov, Evgeny. (2013). To Save Everything, Click Here: The Folly of Technological

Solutionism. New York: Public Affairs.

Nunez, Michael. “Former Facebook Workers: We Routinely Suppressed Conservative

News.” Gizmodo. 5 Sept. 2016. Web.

Rotman, Dana, et al. “From slacktivism to activism: participatory culture in the age of social

media.” Ext. Abstracts CHI 2011, ACM Press (2011).

“Trending – Facebook Help Center.” Facebook. N.p., n.d. Web. 21 Oct. 2016.

Woolf, Nicky. “Remember the Ice Bucket Challenge? It Just Funded an ALS Breakthrough.”

The Guardian. 27 July 2016. Web.