Volunteering at Hand

A critical alternative to matching the needs of communities

Current events in the world, such as poverty, wars, and national disasters, bring forth a rise in volunteering organisations and activities. Therefore, it is surprising that in many countries the volunteering rate is experiencing a slow but steady drop (Kurtzleben 2014), all the while, volunteering tourism is on the rise (Popham 2015). For more and more people, volunteering is becoming an admirable way to spend a vacation – in which they pay thousands of dollars to work in poor communities in countries in Africa, South-America and Asia (this practice is known as ‘voluntourism’). According to Nancy Gard McGehee, an expert on sustainable tourism at the U.S. university Virginia Tech, “as many as 10 million volunteers a year are spending up to $2 billion on the opportunity to travel with a purpose” (qtd. in Popham 2015). Research shows that voluntourism can cause, and is already causing, real harm to communities, in which organisations transform and operate as opportunistic businesses rather than charities (Kushner 2016).

The authors of the study “Volunteering in the European Union” argued that “the problem is not a fall in the number of volunteers, but rather the matching of the needs of volunteers and organisations” (Angermann and Sittermann 2010). Moreover, they argued that “it is getting more difficult for organisations to find people that are willing to volunteer for the long term and/or are ready to assume responsibility in organisations” (Angermann and Sittermann 2010). With our new app, we would like to tackle these persisting problems and offer its users an easy-to-navigate platform on which organisations and volunteers can meet their match. We also hope to persuade those who are interested in volunteering, to invest their time and money more efficiently. Additionally, we hope to inspire people to volunteer and to express acts of compassion and kind-heartedness in their local communities.

Academic intervention

In terms of volunteering opportunities, potential applicants are faced with large amount of, yet often scattered information. It is crucial that people can effectively sort out what is useful from the overwhelming information that is available online. The concept of information overload was traditionally defined as “information presented at a rate too fast for a person to process” (Sheridan and Ferrel 23). In a modern context, information overload can be better described as “not sufficiently organized by topic or content to be easily recognized as important or as part of the history of communication on a given topic” (Hiltz and Turoff 682). This issue is also visible in the case of volunteering opportunities. One problem when searching for volunteering opportunities is that the result will provide one with an endless list of organization or company websites. In order to take a look into detailed information, one should access them separately. Other problems also lie in the existing platforms that try to gather the volunteering opportunities. The categorization is very often not comprehensive and the information available is focused on certain kinds of volunteering opportunities. In order to provide a way to sort out the information the users want, we need to find a method to select information and present it in a more structured and easily accessible way.

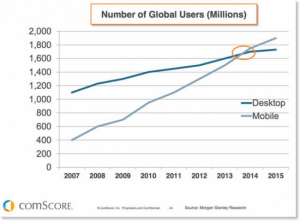

Mobile devices are nowadays a crucial part in new media infrastructure and the trend of switching from computer websites to mobile application is rather obvious. As shown in Fig.1, the number of global users of mobile devices has exceeded that of computers since 2014. And the tendency is that the user number of mobile devices will keep robustly growing.

Fig. 1 Number of Global Users (Millions)

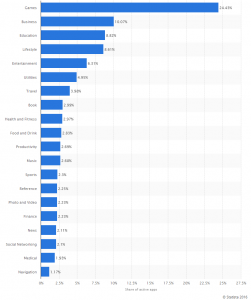

Furthermore, smartphone users are increasingly shifting to using apps as “gateways” to Internet services instead of traditional web browsers (Xu et al. 2011). As a data point, applications have advantages in interactivity, personalization, instantaneity, and accessibility. Our aim was to build an application, which is more up to date with the new media infrastructure, in a field that is of importance, yet is not given enough attention by app developers. Fig.2 below shows the share of active apps on Apple’s App Store. We can observe that developers are focusing more on the profitable fields; therefore designing an application for volunteering is rather necessary.

Fig. 2 Share of Active Apps on Apple’s App Store

The design of the application includes affordances (Gibson 127) and nudges (Thaler and Sunstein 4) that will help with the building of infrastructure and be a way to help solve the problem of “crowdtasking”. According to Gibson, the affordances of the environment are what it offers the animal, what it provides or furnishes, either for good or ill (Gibson 127). The affordances of our app will be the functions that allow the users to do things, for example to search for jobs that are more fitting, to monitor one’s own progress in volunteering, to be actively involved in the user community. Thaler and Sunstein defined “Nudge” as “any aspect of a choice architecture that alters people’s behavior in a predictable way without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic incentives (Thaler and Sunstein 6)”. By matching the skills of the users to the requirements of the organization or company, our app can encourage users into taking the suitable job. Also, we add an element of gamification to our app, the badge system. Badges will be presented as a reward for the time devoted to volunteering work, which will be a nudge to more commitment. The use of badges is a means frequently applied in gamification. According to Bandura, set goals (such as those in badges) increase performance in three ways: (1) people anchor their expectations higher, which in turn increases their performance; (2) assigned goals enhance self-efficacy; (3) the completion of goals leads to increased satisfaction, which in turn leads to increased future performance within the same activities (117-148). The design of our app also includes mapping and visualization of opportunities, in order to nudge users into more fitting positions around them. As mentioned before, people are mistaking voluntourism as volunteering, while neglecting the needs in our own communities. This design can surely help the situation of voluntourism, and lead to better “crowdtasking”. “Crowdtasking” originally refers to the volunteer management in disaster relief (Neubauer et al. 2013), which was raised to improve the volunteer allocation among various tasks during emergencies. This is not only the solution to volunteering chaos during emergencies, but is also the answer to the distribution of volunteering in general. Nudges and affordances will be used in order to guide applicants towards different tasks. Hence, this might be a possible way of matching volunteers’ skills with the organisations that translate the needs of the communities in question instead of catering to the needs of the volunteers – as it happens in the case of voluntourism.

Preliminary Research

In a world of many competing applications, it is important for service and content providers to offer people a user experience that lessens the friction of using their applications. User experience considerations are central in the process of developing an app, as “hardware and network characteristics often exacerbate the difficulties that users face” (Hazaël-Massieux 2013). Trying to develop an app that is one of its kind, amidst millions of apps that are already available in the market, is a really difficult task. However, with Volunteering at Hand we were not aiming for something out of the ordinary, but wanted to design an app that is an improved version of the existing volunteering apps in the Netherlands.

Prior to development of Volunteering at Hand,we conducted an online research of the existing mobile apps for volunteering in the Netherlands. In our research we focused on the interface, intuitiveness and ease of understanding of how to use the app, smoothness and responsiveness of users tasks, immersivity, possibilities for personalization, (language) settings, and content.

Our research showed that there are only nine apps for volunteering in the Netherlands, most of which focused on particular cities, such as Amsterdam, Utrecht, Vlaardingen and Maastricht. Only three apps encompassed the whole Netherlands, out of which only one had actual volunteering opportunities in its database. Moreover, not all apps had an easy-to-use interface, nor bilingual settings (Dutch/English), and lacked in quality content (feed posts and volunteering jobs). However, we did find useful how some apps offered its users a possibility to apply for volunteering jobs with one click of a button. In addition, we were inspired by the app Happy Deed and their feed that allowed its users to share their good deeds and volunteering involvements. With these finding in mind we started working on the development of Volunteering at Hand.

Click HERE to view the development of our app in more details.

Realisation

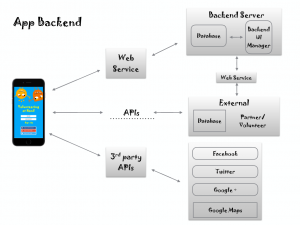

Similar to any other application, our app has two sides (1) the client-side called the frontend and (2) the server-side, known as the backend. As illustrated in figure 3, the backend of our application has both an internal database, as well as an external one. The internal one collects data directly from our users, while the external one introduces new data into the application from partnerships with different organisations and communities, and external volunteer databases. Along with the database, the backend server includes a user interface (UI) manager which as its name suggests, allows us to manage the information which then appears in the frontend of the app. Furthermore, as we offer our user the option to receive support from us via e-mail, the UI allows us to directly check the user’s profile and see what might be his or her problem.

Moreover, 3rd party APIs (application programming interface) are necessary in the construction of the application, because we offer users the possibility to create an account connecting directly with their social media accounts such as Facebook, Twitter and Google+. In addition, a Google Maps API is used for our interactive map via which users can discover possible volunteering jobs around them.

Fig. 3 Application backend scheme

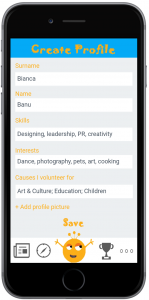

As mentioned above, our internal database is created with the help of our users. The data collected from them is split in two categories (1) data regarding the volunteers (see figure 4) and (2) data regarding organisations and the volunteering opportunities they offer (see figure 5).

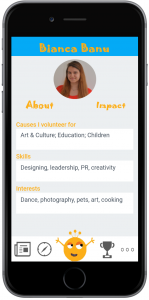

In the first category, the collection of data regarding the volunteers is categorised through different filters present in the frontend of our app. When creating a profile the users are asked to fill in their name and surname, skills (referring to their education and competences), personal interests (such as hobbies or things they are passionate about) and causes they volunteer for (such as education, health, animal care, culture etc.). First of all, in order to create a ‘trustworthy’ community, when filling in a name the users will not be allowed to use any symbols, numbers, unusual capitalisation, punctuations, repeating characters or other such things; that way we will avoid the use of false or offensive names. Secondly, information will be collected, stored and sorted in our database since the moment users create their profile. In case the users chose to connect with their social media accounts, then their profile in our database is also linked to those social media accounts. This collection of data not only allows us to match the needs of organisations and communities with the skills and interests of our volunteers, but also makes it possible to automatically generate a CV that can be send directly to the organisation/community when the user applies to a job through our application.

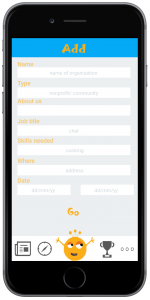

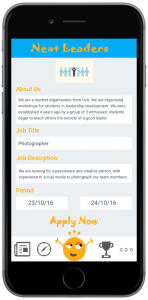

In the second category, the data regarding the organisation, the system works more or less in the same way. When posting a job opportunity the user is asked to fill in the name of the organisation, what kind of organisation it is (community, student organisation, shelter etc), a few words about the organisation, the job title, the skills required for the job, the period in which the job is available, the number of hours the volunteer is needed for the job, and of course a picture with their logo. Hence, after the user fills in this information, the data is sorted and matched with the one collected from the profile of the volunteers.

Fig. 4 User data collection – volunteers

Fig. 5 User data collection – organisations

Our app starts from the problem of voluntourism, deals with the current situation of information overload, and is designed to include affordances and nudges to help “crowdtasking”. It stands as part of the new media infrastructure, functioning as a gateway and data point.

After the launch of our application, a marketing plan will have to be designed in order to promote our application and increase the downloading rate and number of users. However, since Volunteering at Hand is a free application for both the volunteers and the organisations, we had to think of another plan to gain revenue. Therefore, we are going to implement an analytical service which will help us provide reports for different organisations and businesses regarding the volunteering rates – hours invested, causes preferred, age groups, popular areas and so on. For gaining access to this information, a charge will be requested.

All in all, we are aware that the first version of our application might have certain limits and improvements have to be made. For example, the addition of new badges, new filters that will help us better match the needs of organisations and communities with the skills and interests of the volunteers, and implementation of more languages according to the country the application will be available in. For the moment, our main focus is the Netherlands. We will improve and expand our platform based on user feedback, collected data and volunteer demand. When the functions are more complete and page views are stable, we will gradually expand our scope of business to a larger scale, to Europe and then worldwide, stimulating in each country the act of volunteering in local communities.

Scan the QR code or

visit the website https://marvelapp.com/13577a2

to view our App

Bibliography

Angermann, Annette and Birgit Sittermann. “Volunteering in the member states of the European Union – evaluation and summary of current studies.” Working paper no. 5 of the Observatory for Sociopolitical Developments in Europe (November 2010): 7-8. Web. 25 September 2016.

Bandura, A. “Perceived self-efficacy in cognitive development and functioning”. Educational Psychologist 28.2 (1993): 117–148.

Gibson, James J. “The Theory of Affordances.” The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. New York, Hove UK: Psychology Press, 1986. 127-243.

Kurtzleben, Danielle. “Volunteering Hits Lowest Rate in More Than 10 Years.” U.S. News. N.p., 26 Feb. 2014. Web. 23 September 2016. <http://www.usnews.com/news/blogs/data-mine/2014/02/26/volunteering-hits-lowest-rate-in-more-than-10-years>

Kushner, Jacob. “The Voluntourist’s Dilemma.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 21 Mar. 2016. Web. 23 September 2016. <http://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/22/magazine/the-voluntourists-dilemma.html?_r=0>

Neubauer, Georg, et al. “Crowdtasking – A New Concept for Volunteer Management in Disaster Relief.” Springer Link. 2013. Springer Beilin Heidelberg. 26 September 2016. <http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007%2F978-3-642-41151-9_33>

Popham, Gabriel. “Boom in ‘voluntourism’ Sparks Concerns over Whether the Industry Is Doing Good.” Reuters. N.p., 29 June 2015. Web. 23 September 2016. <http://www.reuters.com/article/us-travel-volunteers-charities-idUSKCN0P91AX20150629>

Sheridan Thomas B., and Ferrell Willian R. Mam-Machine System: Information, Control, and Decision Models of Humans Performance. n.p. MIT Press. 1974.

Smart Insights. Number of Global Users (Millions). 2016. Web. 15 October 2016. <http://www.smartinsights.com/mobile-marketing/mobile-marketing-analytics/mobile-marketing-statistics/>

Statista. Share of active apps. 2016. Web. 15 October 2016. <https://www.statista.com/statistics/270291/popular-categories-in-the-app-store/>

Thaler Richard H., and Cass R. Sunstein. “Introduction. ” Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness. New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 2008. 1-16.

Xu, Qiang. Et al. “Identifying Diverse Usage Behaviors of Smartphone Apps.” Proceedings of the 2011 ACM SIGCOMM Conference on Internet Measurement Conference – IMC ’11 (2011): 329-44. Web. 25 Sept. 2016. <http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?doid=2068816.2068847>