Forever Alive: Facebook’s Death Policy and Memorialization

55 is the average age for people to make their will, according to a certified notary. The management and distribution of properties, money and important documents are the most common possessions in these wills. No one ever asked this notary to include their digital legacy neither for elimination nor distribution.

A few months ago, Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook’s CEO announced on his own account that the social platform hit the mark of 2 billion users. But as the number of living users grows; just by 2012 an estimated of 30 million users have died (Kaleem, 2012). Seems not that exciting for the CEO to share this news.

Fig 1. Screenshot of Mark Zuckerberg’s post on Facebook, 2017. https://www.facebook.com/zuck/posts/10103831654565331

The curious case of finding someone dead on Facebook

A month ago, a very peculiar thing happened to me, some of my friends were congratulating this former classmate of mine for her birthday on Facebook; and as I haven’t seen her for some years, I decided to leave a small message. When I was already typing I noticed that her picture was in the middle of the layout with a text on top that said: “In Memory of Renata P”. As I continued to read the birthday messages, I realized that Renata is dead since 2014 and I didn’t know; and worst of all, I was about to leave a funny picture of a sloth with a birthday cake, to wish her many more years and send a very warm hug.

This would have been outrageous for her family, of course, they may have thought I was being disrespectful to the memory of Renata, that I am insensible, rude and I would have been deleted from the friend’s list. But fortunately, none of this happened.

This unfortunate episode, left me with a single thought: Did Renata want all of these people scrolling through her Facebook profile, leaving her comments, liking old pictures, receiving happy birthday messages even though she is dead?

I am almost completely sure that neither Renata nor me or you thought about this when we opened a Facebook account; now you do. Perhaps you want your family to manage your profile, to moderate the comments and messages, to accept new friend requests and give the people you love a platform to keep communicating with you in a sort of digital afterlife. But perhaps you think like me and you just want your social media accounts to be deleted for good and give your loved ones another kind of closure after your death.

The transition from life to death has been honored, celebrated and represented in different ways by all the civilizations, historically the visual displays educated the viewers about mortality (Church 185). We are facing a relatively new phenomenon of memorialization at this time known as Digital Era; Brubaker et al. consider the ways in which Facebook is associated with an expansion of death-related experiences in such ways a temporality, spatiality and socially (152). The experience of grieving with these new digital memorials is changing, and we do not have full control on it, not just Facebook but all the rest of social platforms continue a post-mortem and constant dialogue between the living and the death.

Outnumbering the living

Mark Zuckerberg, proudly expresses on his Facebook account that 1.3 of those 2 billion users, interact with the social media platform on a daily basis; making of this, the go-to 2.0 social platform, being used 4,9 days a week (Forbes, 2015). This means we spend all this time handing Facebook our data; to be more precise, we are constantly writing our autobiographies, and in the moment we pass away, this epos remains forever.

Day by day Facebook gets a number of court orders to release passwords, inbox content, pictures and so forth from the deceased user’s relatives. There is a long list of stories on the web from parents with deceased underage kids that were never friends on Facebook with them and they are seeking to interact with their child’s profile; people looking for evidence to solve crimes, or people just wanting to shut down their loved one’s profile. Perhaps we could make this easier by managing our digital wills.

The French philosopher and social theorist Michel Foucault, vocally expressed his concern in the afterlife of the author, the “author-function” and the legacy of this one in his essay What is an Author? and where do we draw the line between what has to keep being shown after the death of this or not; Foucault thought that “the disappearance of the author is held in check by the transcendental” (303) and by then this is what it must be preserved. As well, Roland Barthes famously said that “literature is that neuter, that composite, that oblique that into which every subject escape, the trap where all identity is lost, beginning with the very identity of the body that writes”. (2)

All these can easily turn into a moral or philosophical debate, as for example Franz Kafka’s case. The German-Czech author was certainly unknown until his friend Max Brod decided to go against his wishes and published most of Kafka’s work after this one died. Undoubtedly Franz Kafka’s books and writing style defined the 20th century literature and as some of his biggest admirers would defend Brod’s actions claiming that “the world deserved to see his work”, we can take a moment and reflect about the moral connotations of the posthumous usage of these texts, and worst of all, the action of profit from them.

The current use of all these 2.0 social platforms makes us as likely to inherit a USB stick or a compilation of internet passwords as a bunch of important documents or money. And as Massimi and Charise analyze, “What about those who don’t wish to live forever, or who want their relationships with technology (and future readers) to die with them?” (6)

If we decide to start making decisions about our digital legacy, we can find different websites with all sorts of options like LastPass, where you can manage the distribution of the passwords, NIP codes, bank account numbers, fidelity cards and more. Another option could be Eternime, a site that claims that you could live forever as a digital avatar, so your friends and family could interact with a digital version of you after your death.

Every person should be able to decide this in the moment of opening a Facebook account; the social platform just wants you to provide information about you; like your birthday, your job, your education, favourite food, favourite quote, relationship status or political inclination; but there is no apparent guidance or option to decide what to do with your digital legacy.

How to take action

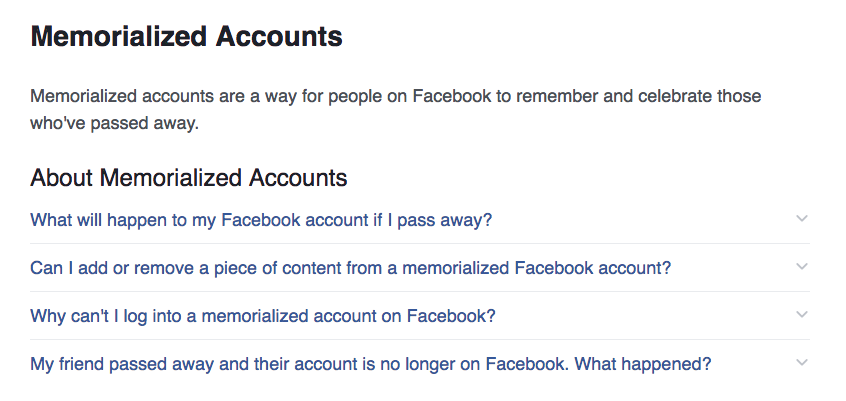

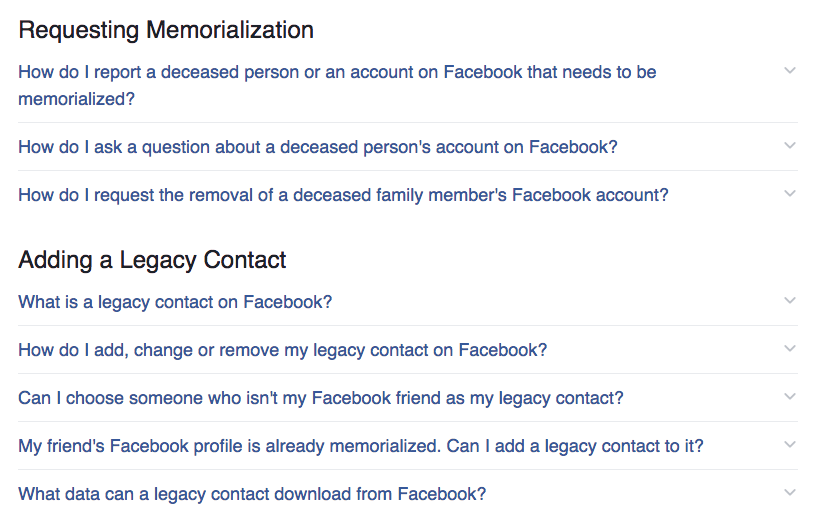

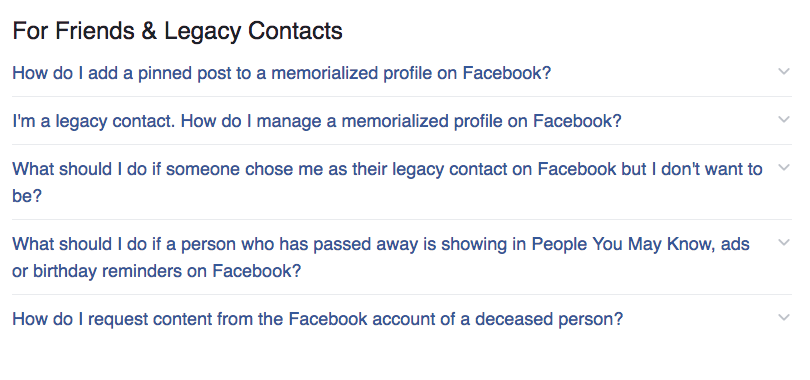

Facebook offers a couple of quite well-hidden tools to either memorialize a profile or eliminate your digital remains after someone reports you as deceased. Strangely this “death policy” is in constant change and perhaps what I am explaining today, won’t be valid tomorrow. A few days ago, while working on this blog entry, I made the decision of making a choice for my post-mortem Facebook profile and I had these two options I already expressed; you can choose a Legacy Contact or the “total” elimination of the account.

It is important to say that I couldn’t find it myself in the Facebook interface; I had to search for it in Google as “Facebook Death Policy” which emitted these options after I clicked on the first link:

Fig. 2, 3 & 4 Screenshots of the Facebook Help page, 2017.

https://www.facebook.com/help/1506822589577997/

I chose the first option; what will happen to my Facebook account if I die? and to explore both of the options I selected a friend to be my legacy contact and she got immediately a message with the following information translated into English from Spanish:

Hello, Sandra: Facebook allows people to choose a contact to manage your account if anything occurs.

(followed by a link from Facebook Help)

I chose you because you know me well and I trust you. Get in touch with me if you want to talk about the subject.

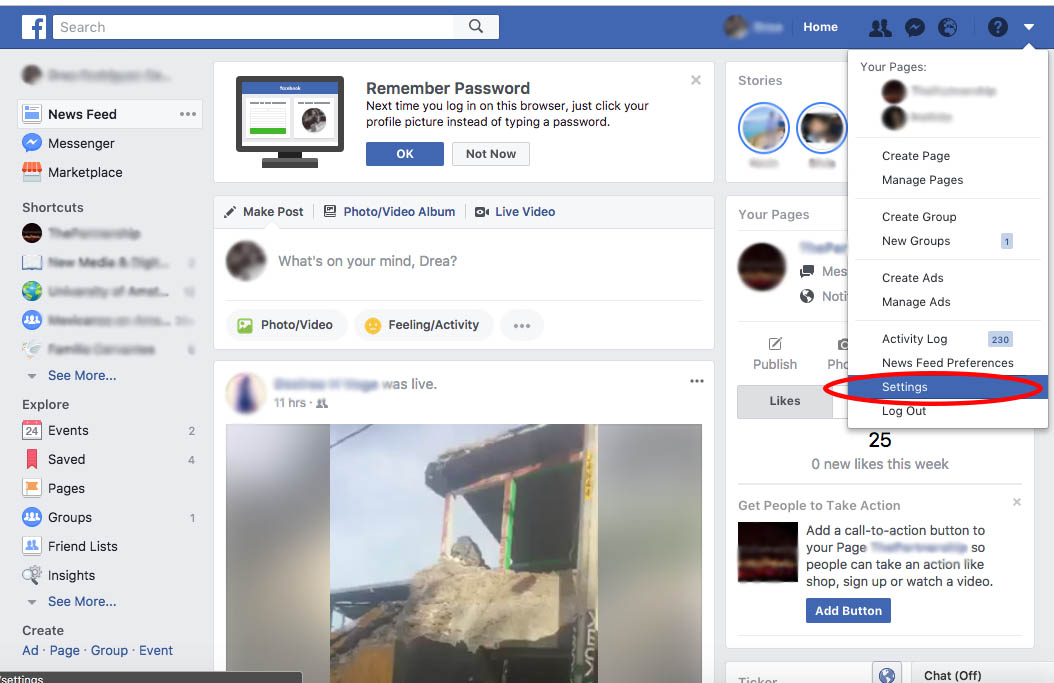

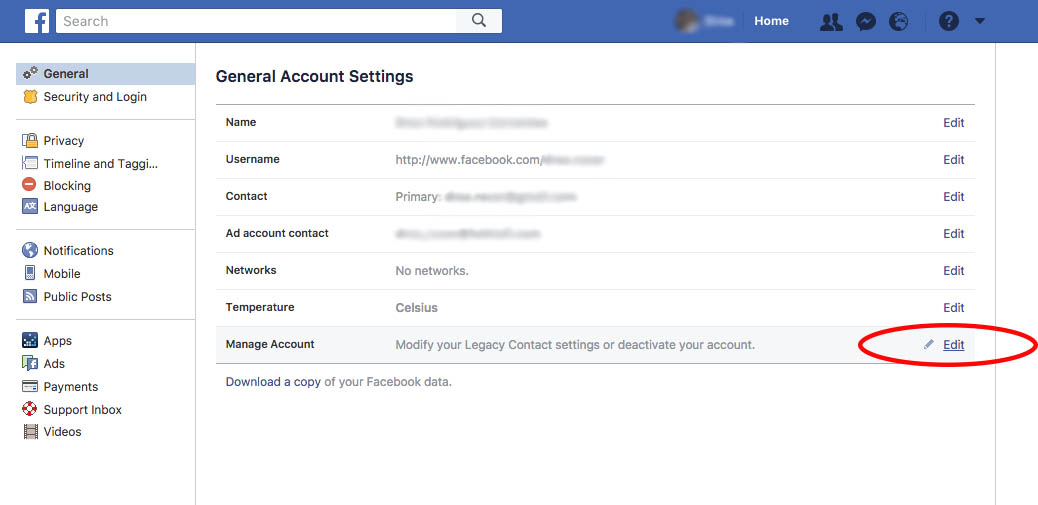

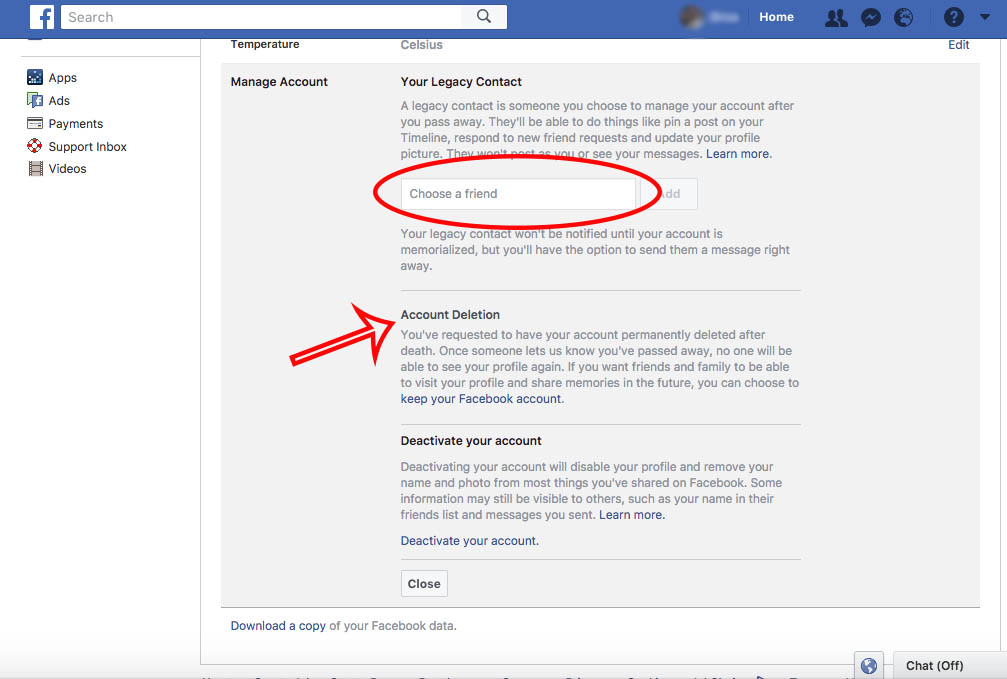

Then I decided to revert this and choose the option of eliminating my account after I pass away by going to Settings > General > Manage Account > Edit > Your Legacy Contact.

Fig 5, 6 & 7 Screenshots of the Facebook Settings, 2017.

https://www.facebook.com/help/1506822589577997/

Conclusions

The internet gives us the illusion of have overcome death, to offer a new kind of ritual of memorialization by providing a close resemblance to a romantic gravescape (Church 187) in the layout of the deceased profile, Facebook does not seem to be entitled to deal with these complexities and should provide a legal solution apart from religious beliefs or traditional post-mortem rituals; providing a very clear and easy to access option to its users to delegate, distribute and manage their data and create a digital will for the accounts that are part of the “Facebook Family”.

As well the education on this matter to young users and current users would simplify the work of the bereaved families and friends as protocols and norms related to online mourning are still being constantly developed. (Lingel 194) The fascination toward the death is an inherent behavior of the human being, and nowadays the Internet plays the role of the medium in which we are leaving day by day a digital trace that will probably live forever, and if it’s not handled responsibly could end in the wrong hands. By now we do not have full control of what happens to these digital remains as depends on a number of factors and arrangements of third parties (McCallig 112) but there is a big difference to be made by at least taking care of what we share and by spreading the word about this matter. In the end “the life of the dead is placed in the memory of the living” -Marcus Tullius Cicero.

Notes

The names of the people mentioned were changed in order to protect the privacy of the individuals.

References

Barthes, Roland. “The Death of the Author.” Image / Music / Text. Trans. Stephen Heath. New York: Hill and Wang, 1977. 142-7

Brubaker, Jed R., et al. “Beyond the Grave: Facebook as a Site for the Expansion of Death and Mourning.” The Information Society, vol. 29, no. 3, 2013, pp. 152–163., doi:10.1080/01972243.2013.777300.

Church, Scott H. “Digital Gravescapes: Digital Memorializing on Facebook.” The Information Society, vol. 29, no. 3, 2013, pp. 184–189., doi:10.1080/01972243.2013.777309.

“Eternime.” Eternime, www.eterni.me/. Accessed 24 Sept. 2017.

Foucault, M. What is an author? The Foucault Reader. Pantheon, New York, New York, 1984.

Kaleem, Jaweed. “Death On Facebook Now Common As ‘Dead Profiles’ Create Vast Virtual Cemetery.” The Huffington Post, TheHuffingtonPost.com, 7 Dec. 2012, www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/12/07/death-facebook-dead-profiles_n_2245397.html. Accessed 24 Sept. 2017.

Lingel, Jessa. “The Digital Remains: Social Media and Practices of Online Grief.” The Information Society, vol. 29, no. 3, 2013, pp. 190–195., doi:10.1080/01972243.2013.777311.

Massimi, Michael, and Andrea Charise. “Dying, death, and mortality.” Proceedings of the 27th international conference extended abstracts on Human factors in computing systems – CHI EA 09, 2009, doi:10.1145/1520340.1520349.

McCallig, D. “Facebook after death: an evolving policy in a social network.” International Journal of Law and Information Technology, vol. 22, no. 2, 2013, pp. 107–140., doi:10.1093/ijlit/eat012.

“Preparing a Digital Will for Your Passwords.” The LastPass Blog, 28 Oct. 2016, blog.lastpass.com/2016/04/preparing-a-digital-will-for-your-passwords.html/. Accessed 24 Sept. 2017.

Multimedia:

Meyer, Frerk. 2013 <https://flic.kr/p/fLygtx>