New Google Feed: What about privacy?

In July of this year, Google Inc. delivered a new feature for its Google app called Feed. This addition transforms the front page of the app into a news and information feed, where news articles and suggestions are presented according to the search and Chrome browsing history of each individual user.

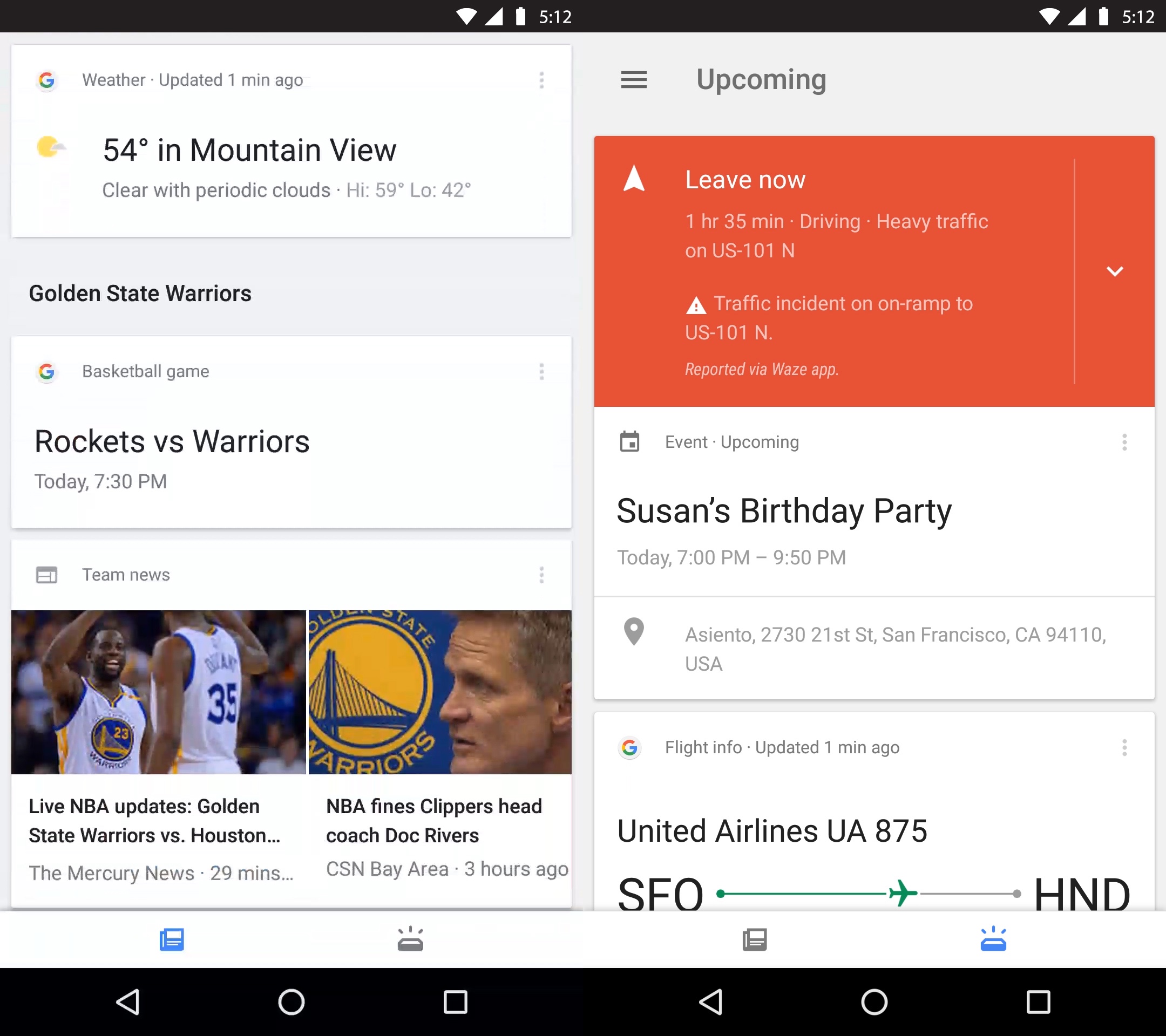

This feature was first implemented in the phones of iOS and Android users, however Google Inc. is also planning to transfer this feature onto desktop versions of the app (Matney n.pag.). To be more precise, this new feed incorporates news that are linked to previously searched themes by providing various news outlets that cover the same topic (Matney n.pag.). This could be seen as done in the hopes to offer multiple perspectives and thus unbiased news. In addition to news stories, the feature will offer local information about interesting topics, customized to each individual user. As Google Inc. has access to users’ search history and current location the feed can suggest music events, art galleries, various events and sports results based on individual preference (Matney n.pag.). The whole feed can be personally customized by removing news stories and topics, or adding interesting topics by searching and clicking ‘follow’ (Freedman n.pag.). Similarly to social media platforms, Google feed offers the option to follow and share articles through Facebook, Twitter and other sites. Due to the nature of the news feed, Google will now be in competition with several social media sites, such as Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn that have long implemented similar features. Generally, this addition can be seen as copying, seeing that similar objectives are already being filled by other sites. Yet Nelson Granados suggests that Google feed is an emergent update and will actually fill a gap by offering unbiased news, which social media sites have yet to accomplish (n.pag.). An example would be Facebook that offers articles based on the personal views of your friends, deeming its system quite partisan.

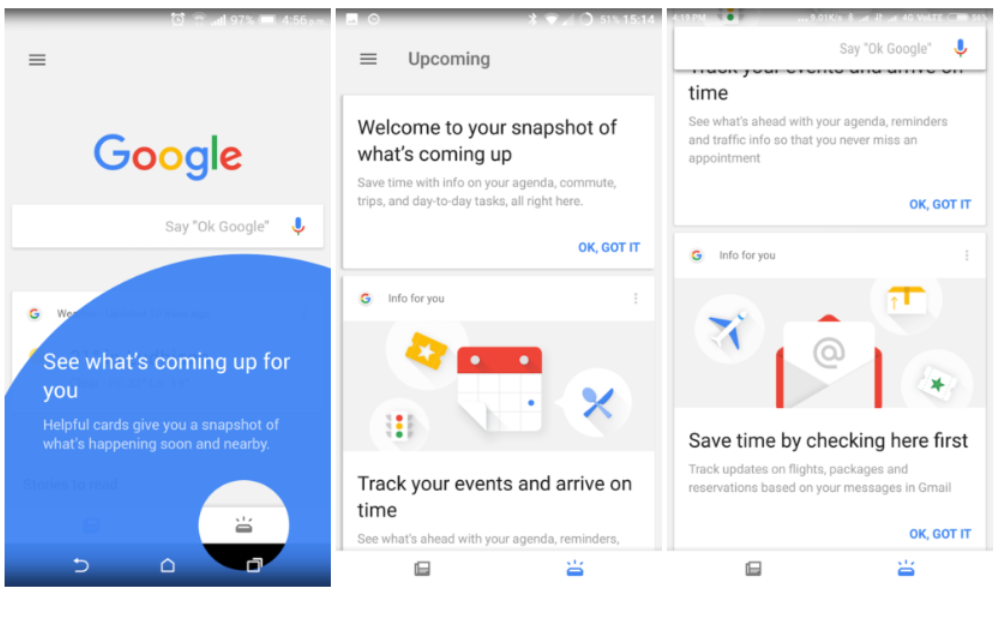

Google feed is composed by several parts, such as news, events and personal calendar.

On the hole, Google feed allegedly offering unbiased news is subject to a wider debate about whether news can be unbiased and how.However this debate will not be further explained, as the attention is rather put on the debate around big data and privacy. In the case of Google Inc., big data is more specifically tied in with the news feed on the Google app. In order for the Google app to provide each user with customized content, a large amount of data from each user has been collected and analyzed over time. This large collection of data, also called Big Data, is seen to have both positive and negative aspects and has sparked two different schools of thought among academics (Baltus n.pag.). Firstly, computer engineers and scientists who mainly consider the positive technological implications, and secondly the more socio-technical view that considers broader social and managerial implications of Big Data (Baltus n.pag.). From the more sociotechnical perspective the use and collection of Big Data raises concerns about online privacy and specifically how data is collected and what happens to the gathered information.

Example of what Google feed offers its users: personal information such as flight reservations, birthdays and everyday routes are provided.

Some academics within the socio-technical framework have combined the conceptual framework of law, politics and philosophy to understand privacy expectations and their outcomes. For example, the ‘privacy as contextual integrity’ approach developed by Hellen Nissenbaum, offers a perspective to processing personal information, the most important part of which is the exchange of data that corresponds to contextual norms. Contextuality refers primarily to the purpose for which the data is to be processed, and the corresponding rules for the participants’ roles and data void (Nissenbaum 119). More specifically, Nissenbaum explains the framework as follows:

“Contextual integrity ties adequate protection for privacy to norms of specific contexts, demanding that information gathering and dissemination be appropriate to that context and obey the governing norms of distribution within it.”(Nissenbaul 101).

According to Nissenbaum, in almost all contexts there are standards for information and distribution (106). It distinguishes between the two types of information transmission standards – appropriateness and distribution standards – compliance with which helps to maintain contextual integrity (Nissenbaum 106). Contextual integrity includes time, place, practice, cultural traditions and other aspects that regulate and influence individual’s life events (106). Norms of appropriateness determine which information is or is not suitable and acceptable to be disclosed about an individual in a particular context, the norms of information distribution are on the other hand related to free choice and discretion, as well as to necessity and obligation, that is, when disclosing information is or is not appropriate and acceptable (106). Appropriation and distribution standards are particularly important when it comes to sensitive information, which when being widespread can have negative consequences.

This approach is also shedding light on the unfounded privacy agreements of Google, which promise to not disclose overly personal information. In reality information collected by Google Inc. is already automatically shared with third parties once the user has searched for something. Although, major search engines have argued that they retain personal information for the provision of a better service, they also store such data for more than a year, which is a much longer time unit than is actually needed. Through Google it is possible to identify, for example, political and religious views, perceptions of the worldview, identification of ethnicity and race. Google stores what information is searched and saves everything for an indefinite amount of time, thus making it possible to identify what is the user’s lifestyle, habits and needs (Prabhu n.pag.)

Already in 2012 through harmonizing all the privacy policies of its different services Google brought about major changes to user privacy terms. Nevertheless, as pointed out by Moscaritolo, most users did not know anything about this, even though the information was made available (n.pag.). This awareness aspect has left users to become more passive, as new conditions apply even without the informed consent (n.pag.). Through becoming more passive, users unknowingly give big data collectors the advantage to use various techniques and gather more information about the consumer. According to Griffin, similarly to gathering information from what people type into Google search on their computer and phone, Google Inc. also implements the user voice and sound recording feature on phones through voice commands and built-in voice assistants (n.pag.). This history of voice recordings is also linked to the user’s Google account and is used by Google to suggest new stories, events and practical information on the Google app feed (n.pag.). As Griffin suggests, many are not aware of this data being stored during the time of use (n.pag.).

Furthermore, Google Inc. has access to user locations. Regarding location privacy, it is possible to determine the approximate location of a user’s computer or device using a variety of technologies. For example, using the search engine, you can find a more or less precise location based on the IP address of the computer or phone (Matt n.pag.). Information about user’s location can be used for useful purposes, for example, by showing the weather forecast for the current city in the phone. However, this may be a major risk to privacy if the user’s location information is collected in the database and merged with other sources or shared with third parties. On this basis, it is possible to find out the user’s habits of behavior, for example, which route is used for home or work. Based on this information, one can predict where the user currently is, even if direct monitoring through technology is not possible. (Matt, 2014). All this sensitive information has premises to be used in contrast with contextual integrity, as third parties do have their own rules and regulations to information use that might not be in cooperation with the ones of Google Inc. and/or the country of user’s origin.

Overall, the downside of search engines like Google and its extensions on the Web is that once personal data is set up in the public Internet space, it is virtually impossible to further control what happens to it. Looking at the notion of privacy of the feed on Google app through the lens of contextual integrity It is no longer possible for Google Inc. to claim that no confidential information is used as already the ways of gathering user information are designed to create an all-knowing search engine, catering to each individual separately. Thus the answer to the question to whom Google Inc. shares its information in the back end remains not all too clear, as some indications are provided in the privacy statement, yet as the contextual integrity theory suggests the appropriateness of personal information distribution still remains a big concern for Big Data companies. Uses for confidential Big Data, such as what Google collects through its technology, does seem to have the foundation of providing better services in the hindsight, however the further uses for information are not as transparent as one could expect (Moynihan n.pag.). Going back to the more specific addition to the Google app, the feed, the premises on which its functions are built on, expect some information to be collected from the user in order to provide promised services. Nevertheless, the extent to what kind of information is collected and to whom it is shared might not always be justified.

In conclusion, considering the perspective of contextual integrity, online privacy for individuals with regards to search engines like Google could possibly be improved, may this be by constructing regulations and procedures, or designing new technologies that make the use of online search engines more private.

References

Baltus, Quentin. “Understanding big data key debates and controversies: a critical literature review“. LinkedIn. 2016. 23 September 2017. <https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/understanding-big-data-key-debates-controversies-critical-baltus>

Freedman, Andrew E. “The New Google Feed: What It Is And How It Works”. Tom’s Guide. 2017. 23 September 2017. <https://www.tomsguide.com/us/google-feed-faq,news-25496.html>

Granados, Nelson. “How The New Google Feed Can Outperform Facebook”. Forbes. 2017. 21 September 2017. <https://www.forbes.com/sites/nelsongranados/2017/07/26/how-the-new-google-feed-can-outperform-facebook/#6352093a6f90>

Griffin, Andrew. “Google voice search records and keeps conversations people have around their phones – but the files can be deleted”. Independent. 2016. 24 September 2017. <http://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/gadgets-and-tech/news/google-voice-search-records-stores-conversation-people-have-around-their-phones-but-files-can-be-a7059376.html>

Klein, Matt. “Google’s Location History is Still Recording Your Every Move”. How To Geek. 2014. 22 September 2017. <http://www.howtogeek.com/195647/googles-location-history-isstill-recording-your-every-move/>

Matney, Lucas. “Google introduces the feed, a news stream of your evolving interests”. TechCrunch. 2017. 22 September 2017. <https://techcrunch.com/2017/07/19/google-feed/>

Moscaritolo, Angelo. “Most Users In the Dark About Google’s New Privacy Policy”. PC Magazine. 2012. 23 September 2017. <https://www.pcmag.com/article2/0,2817,2400868,00.asp>

Moynihan, Tim. “Alexa And Google Home Record What You Say. But What Happens To That Data?”. Wired. 2016. 22 September 2017. <https://www.wired.com/2016/12/alexa-and-google-record-your-voice/>

Nissenbaum, Helen. “Privacy As Contextual Integrity”. Washington Law Review Association. 2004.

Prabhu, Vijay. “EFF lodges complaint with the FTC, alleging that Google is mining student data without permission”. Techworm. 2015. 24 September 2017. <https://www.techworm.net/2015/12/eff-claims-googles-chromebook-stores-students-data.html>